Sam Kean. The Bastard Brigade: The True Story of the Renegade Scientists and Spies Who Sabotaged the Nazi Atomic Bomb. Little, Brown, 2019. 464 pp. $30.

Paris: August 25, 1944.

By the time Boris Pash and three of his soldiers reached the City of Light, it had been under Nazi occupation for more than four years. Pash was the military commander of the Alsos Mission, a brigade of soldiers and scientists whose objective was to monitor and impede the progress of the German atomic-weapons program. They were to comb Europe for scientific personnel, records, atomic material, and sites and, while they were at it, keep the Soviets in the dark. Kidnapping and assassination were not off the table. On this summer morning Pash had his eyes set on a target that had eluded him for some time: Frédéric Joliot-Curie, Nobel Prize–winning chemist and rumored Nazi collaborator.

The Allied forces had beaten back the Nazis around Paris over the previous six days. But the French troops, who craved the honor of being first into their capital city, were blocking access to other Allied soldiers. Pash, not the most patient of men, had taken to heart an admonition from Washington: “Any slight delay in reaching your targets might cost us tremendous losses, or even the war.” He was not about to let Joliot-Curie slip through his fingers, and so he did what anyone in his position would do: he lied.

Approaching the French barricade on the road to Paris, Pash tracked down the officer in charge. As Sam Kean writes in his chronicle of the Alsos Mission, The Bastard Brigade,

It wasn’t long before the major realized his mistake and informed his superiors that the Americans were making a break for Paris. Kean writes, “[The French] were furious—those dirty Americans! They had no choice but to start marching. In a roundabout way, then, Pash’s trick spurred the liberation of Paris.”

Readers of Kean’s previous books can see from even these snippets that his playful, sparkling voice is alive and well, even though The Bastard Brigade is a departure on two fronts (no pun intended). First, it returns him to an early love: physics. Kean majored in the subject in college, but his previous books are about chemistry, neuroscience, the atmosphere, and genetics. Like any good storyteller he was waiting for the right material to come along, and the history of the Alsos Mission was too good to pass up.

Second, while Kean’s other books comprise vignettes on a given subject, with The Bastard Brigade the author takes a novelistic approach. The book follows not only the Alsos Mission but two other nuclear subplots: the numerous sabotage missions conducted by the Norwegians and British on the Nazi-controlled Vemork heavy-water plant in occupied Norway (heavy water being used in nuclear research, and Vemork being the only plant in the world that produced it), and the military adventures of Joe Kennedy Jr. and his missions targeting potential atomic sites. Most of the time, however, we’re with the men of the Alsos Mission on their various assignments—and they make for a motley crew.

Pash was born in San Francisco in 1900, the son of a Russian Orthodox priest. After moving to Russia with his family during his teenage years, he returned to the United States, got a degree in physical education, and started teaching chemistry and coaching baseball at Hollywood High School. He also joined the Army Reserve and began working in intelligence.

Pash may have had a Russian upbringing, but he was “passionately and belligerently anti-communist.” So when he was assigned to the Manhattan Project and given security duty, he was eager to root out communist spies—particularly, he believed, Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory. “We never let Oppenheimer out of our sight,” he said. “We knew his every step. Every letter was read, every telephone call was overheard, every contact checked and studied.” (Not all those tactics were legal, by the way.) General Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project, was impressed by Pash’s thoroughness and tapped him to be the military commander of the newly formed unit dubbed Alsos. (Alsos means “grove” in Greek, an inside joke that enraged the general, who feared the brigade might be traced back to him.)

The scientific head of the Alsos Mission was a man named Samuel Goudsmit. Born in the Netherlands to Jewish parents, Goudsmit had discovered quantum spin when he was only 23 years old, but he later struggled to live up to this early promise. His connections to other physicists, particularly his friend Werner Heisenberg, a German theoretician, made him an attractive prospect for the new Alsos Mission. But mostly, according to his personnel file, “Dr. Goudsmit has been recommended principally because he is available.” Ouch. He was also personally invested in a way other members of the brigade were not: his parents went missing from their home in The Hague in 1943, and their last known whereabouts indicated they were in a concentration camp.

Goudsmit and Pash had very different personalities and didn’t get along—until August 1944, that is. At the moment Pash was accidentally spurring the liberation of Paris, he was supposed to be meeting Goudsmit at the airport in Cherbourg, more than 200 miles away. Goudsmit had to scrounge around for a ride to the army headquarters in Rennes, where he assumed Pash would be. No Pash, as it turned out, and the soldiers in Rennes were no help. As Kean remarks, “A scientist didn’t merit a ride anywhere, let alone Paris.” Goudsmit wasn’t even supposed to leave the area, though a general lent him a jeep and a driver for errands around town. Goudsmit asked his driver what the general’s orders were. “He told me to take you wherever you want to go,” the driver replied. “Paris!” cried Goudsmit. They went, and the angry general reported the jeep stolen. Word got to Pash, and when Goudsmit arrived, he desperately tried to explain himself—until he saw Pash, a bit of a rule breaker himself, grinning. This little caper finally endeared Alsos’s scientific commander to its military commander.

By then Alsos had found Frédéric Joliot-Curie. He hadn’t been at the family home in the coastal town of L’Arcouest, and he hadn’t been at his home in the Paris suburbs. Pash’s mad dash through the lines had been in the direction of the Joliot-Curie lab. Most intelligence reports had painted Joliot-Curie as a Nazi collaborator since his lab was overrun by German scientists, but it turned out he was part of the French Resistance and used his considerable chemistry skills to make Molotov cocktails. He knew his reputation, though, and greeted the Americans with much enthusiasm, relieved to set the record straight.

Joliot-Curie wasn’t the only jewel in the brigade’s crown. Alsos collected several of Enrico Fermi’s colleagues from Italy along with most of Germany’s elite atomic scientists: Otto Hahn, Max von Laue, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, and Werner Heisenberg. Goudsmit’s friend Heisenberg, in fact, was almost assassinated by an Alsos agent while delivering a speech at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology on December 18, 1944. The agent’s instructions were to pose as a physicist, attend the lecture, and, if Heisenberg incriminated himself by spouting anything about the German weapons program, assassinate him where he stood. Fortunately for Heisenberg, his topic of choice that day was S-matrix theory and the hope that it could reconcile quantum mechanics and general relativity. Heisenberg lived to be captured by Pash the following May.

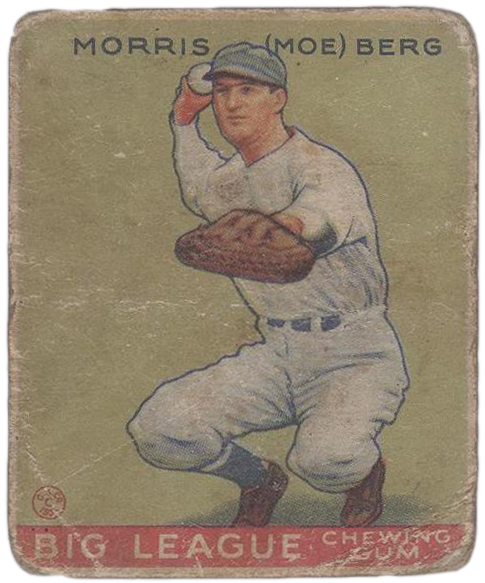

In one of the weirder aspects of this whole story, the would-be assassin was a man named Moe Berg—a former Major League Baseball catcher. Famed manager Casey Stengel once called him “the strangest man ever to play baseball.” Berg had a penchant for taking classes at the Sorbonne in the off-season, he skipped spring training to go to Columbia Law School, and he often read 10 newspapers at once. His facility with languages and his connection with Japan through baseball made him a skilled if unconventional recruit to the Alsos Mission, even if he was a bit of a flake when it came to his official espionage duties. Nevertheless, Berg’s is the only baseball card on display at CIA headquarters.

It wasn’t just people that Alsos tracked down; sometimes it was uranium. When the Germans conquered Belgium, part of the prize was the largest stockpile of uranium in Europe. Most of it had been shipped to France, but there was a hefty portion left behind in a refinery about 30 miles from Antwerp. In September 1944 a group of Alsos commandos orchestrated an assault on the well-protected refinery. With walls on three sides, a canal on the fourth, and German machine-gun fire coming from across the canal, Pash and his team, like action heroes in a movie, used an elevated railroad crossing as a ramp to launch their vehicles into the refinery.

Once that uranium was secured, they headed to France to collect the remainder of the load. France was an ally, yes, but it was not at all disposed to give the Americans the uranium. Pash had to threaten its keepers with the machine guns mounted on his jeep before they’d let it go. Ultimately the French and Belgian uranium was shipped to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and ended up in the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima.

Kean delights in sharing these lesser-known stories of scientific derring-do in ways both fun and informative, an approach familiar to readers of his earlier books. Kudos to him for experimenting with a more novelistic approach, convincing me that he can tackle any format he wants. If I have a quibble, it’s that the book doesn’t stitch the Norwegian and Kennedy subplots into the greater whole. If you’re like me, you’ll want to know that in advance instead of wondering when the three stories will intersect—because they never will!