Benjamin Gross. The TVs of Tomorrow: How RCA’s Flat-Screen Dreams Led to the First LCDs. University of Chicago Press, 2018. 288 pp. $40.

I watch a lot of TV, probably much more than I should admit as the author of a book review. Yet despite the hours spent gazing happily at the screen, I have never actually purchased a television. All of my TVs have come as hand-me-down gifts—from friends, family, or former roommates—as everyone around me upgraded. Black-and-white TVs gave way to color, and smaller sets with grainy resolution were followed by larger screens with better pictures. My most recent TV, which gave up the ghost just last year, came with the house: the previous owner had decided the old tube television was too heavy to move. The 40-inch Mitsubishi console set, encased in an oak cabinet and clearly top of the line when new in 1989, fit perfectly with the shag carpet and paneled walls of my 1964 split-level.

As I contemplated a replacement set, I realized how much my viewing habits had changed over the past decade. Long ago I cut the cord with cable, and I rarely watch real-time broadcast TV anymore. I stream almost everything on my laptop, tablet, or even my phone. Flat-screens are the new normal. Today I’m not even sure I could purchase a tube television outside of a secondhand shop, and in recent years I have seen more of them made into aquariums than used as functioning sets. The fact that I can carry in my hand a screen with such beautifully clear resolution, significantly better than that old behemoth in my living room, seems all the more improbable now that I have read Benjamin Gross’s book The TVs of Tomorrow.

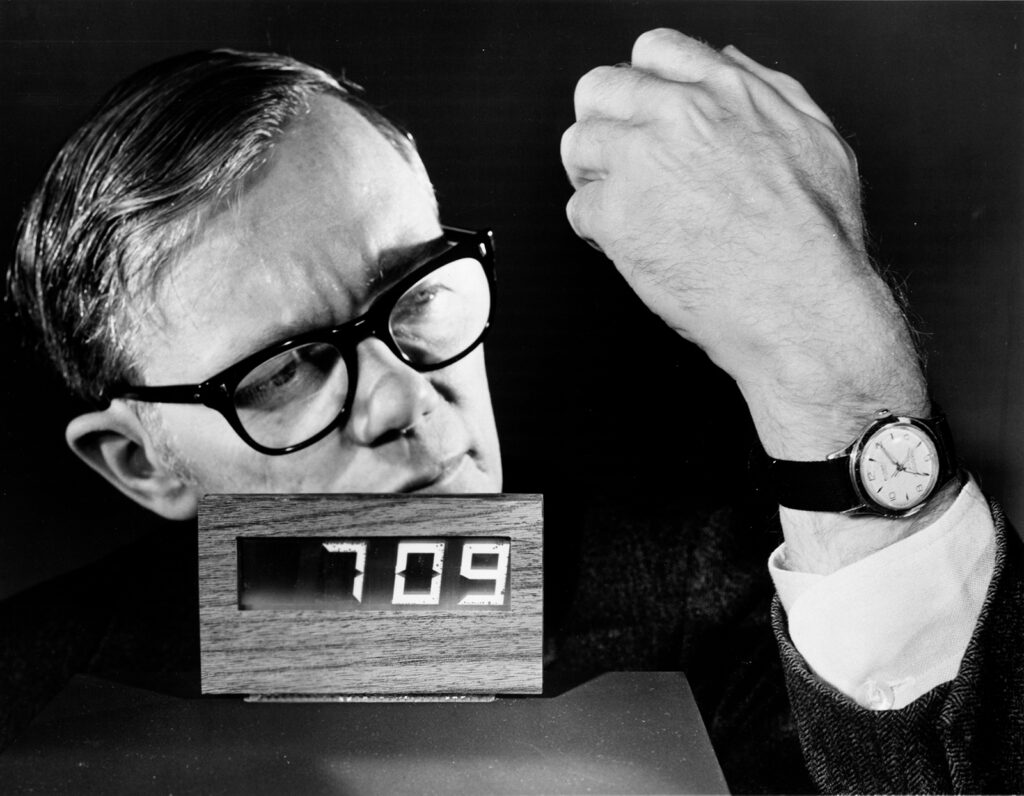

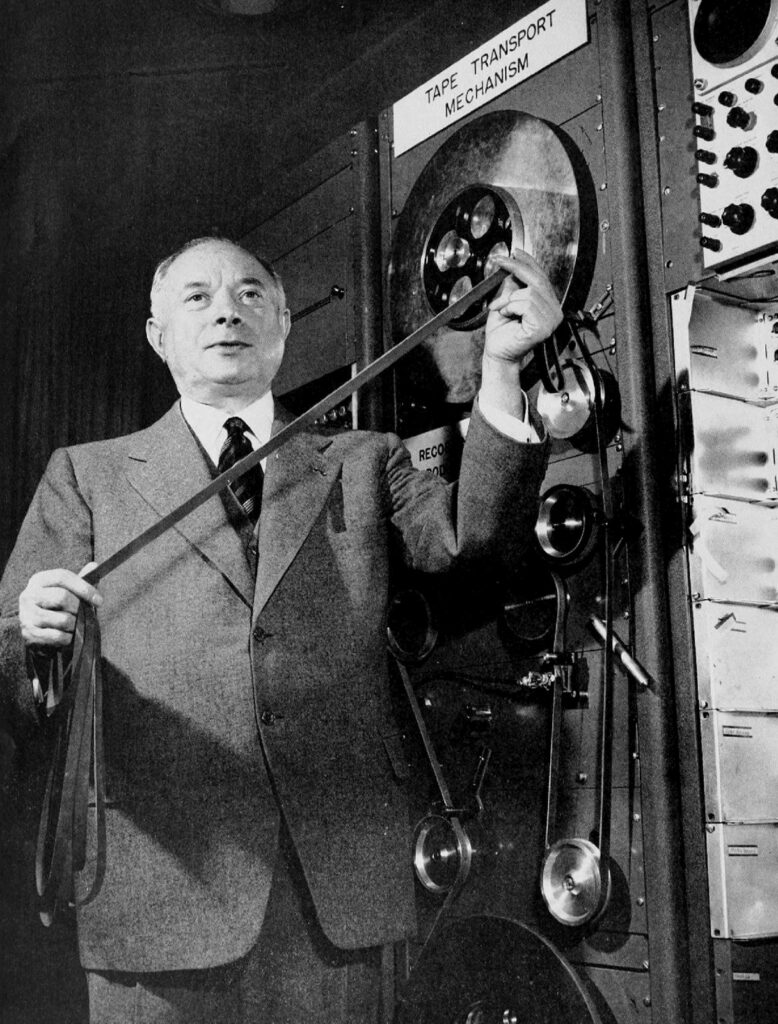

Gross begins his tale with a Radio Corporation of America (RCA) press conference held in 1968 that introduced to the world the curious properties and possibilities of liquid crystals. James Hillier, the vice president in charge of RCA Laboratories, packaged the announcement as a research breakthrough. He acknowledged it would be some time before applications hit the market, though he clearly hinted at future products. Scientists had been researching liquid crystals in academic labs for decades, but RCA researchers were the first to show how electric fields could be applied to manipulate light passing through liquid crystals and so create images on a relatively thin display screen. Predictions quickly followed for all manner of consumer electronic devices: clocks, calculators, even a television that could be hung on a wall like a picture frame.

In an era of heavy glass screens and bulky cathode-ray tubes, a flat-screen TV sounded fantastical. Perhaps even more absurd was the suggestion—made by Hillier himself—of a portable screen you could take to the beach! But RCA had a well-deserved reputation for innovation, so the press could be forgiven for thinking flat screens could be the next big thing. Similarly, today’s reader who knows only of the successes of liquid-crystal display (LCD) screens, in such products as televisions, computer monitors, tablets, and smartphones, might be forgiven for thinking this a story of natural progression in technology. Instead, Gross makes clear that nothing was inevitable. The result chronicles determination and struggles, with the research always teetering on the brink of breakthrough or immediate cancellation.

Gross frames his story around an ambiguous request made by RCA chair David Sarnoff at his 60th birthday celebration. Sarnoff, a commanding leader who liked to be called “the General,” looms large throughout the book. At the party he asked his “family” of researchers to discover “a true amplifier of light” that “would provide brighter pictures for television which could be projected in the home or the theatre on a screen of any desired size.” Sarnoff’s request became a strategic vision that led chemists, physicists, electrical engineers, and many others doggedly down a particular research path.

After introducing Sarnoff’s end goal of a flat-screen TV, Gross backtracks to 1951 as researchers begin to understand materials that have the mechanical properties of liquids but the regular molecular structure of a crystalline solid. The narrative tells of investment in basic research, with scientists who had the freedom to explore possible applications. But it is also a business history, with RCA looking to capitalize on inventions and scientists and engineers pressured to find potential markets. Still, what stands out is the length of time given to the LCD research group to pursue the dream of flat-screen TVs. For a company to invest in decades of research with little return on investment seems inconceivable in today’s climate of quarterly reports and instant Twitter updates.

As the realization of a flat-screen TV remained elusive, shifts in company priorities created challenges for the group. Complaints of budget and staff cuts echo through the years. With the clarity of hindsight sympathy for the struggling researchers comes easily. Perhaps if they weren’t worrying about next year’s budget or if they could have kept one more technician on the team, success might have come. Sometimes, though, it just sounds like whining from scientists who are no longer the General’s favored children.

But remember this is not a story of inevitable progress. Management’s justifications for cutting research funding are plain to see. The LCD team repeatedly failed to understand the differences between successful laboratory experiments and industrial-level production. It is, however, a story of lost opportunity. By focusing on the golden ticket of an LCD television, RCA missed smaller opportunities—using LCDs for digital clocks, watches, and calculator screens, for example.

RCA ultimately failed to capitalize on its LCD research, and I’d normally offer a spoiler alert before revealing that sort of information. But Gross states on page 4 that RCA abandoned its LCD research in 1976, long before consumer-level flat-screen TVs were finally realized. What kept me engaged is this foreknowledge of RCA’s failure along with a simultaneous wonder at the LCD’s success. After all, many readers will peruse Gross’s story of successful invention but failed innovation on a Kindle screen.

Gross has examined RCA’s lab notebooks and archival records in meticulous detail. He also knows his science, and the book gives comprehensive explanations of key developments, such as Wolfgang Helfrich’s proposal for a new type of LCD involving a twisted nematic helix inside a sandwich cell placed between a pair of crossed polarizing filters. These explanations might overwhelm a casual reader in search of a history of TV but will be a welcome change for those scientists and engineers who complain that historians skimp on the painstaking process of discovery.

In other words, this book is not about the content of television shows or about the infrastructure required to create television networks. (Gross never pretends otherwise.) It is about the engineers and scientists at a single company who doggedly pursued a technically difficult problem, even after RCA’s leadership lost interest in their work.