In 1865 a celebrated British army surgeon died of dysentery. There was nothing strange about the death—dysentery was a common killer. Instead, it was the scandal that followed that rocked British society.

According to reports, the surgeon, James Barry, had not been all that he had seemed. While washing the doctor’s body after his death, a charwoman discovered that he was, in her words, “a perfect female.” The Manchester Guardian responded to this news with gusto: “Were not the truth capable of being vouched for by official authority, the narration would certainly be deemed absolutely incredible.” Some of Barry’s acquaintances reacted with shock; others claimed to have always suspected Barry was not a man. Two years later, none other than Charles Dickens wrote that it was “a mystery still” as to how the good doctor had fooled so many people for so long.

More recent writers have taken a different view of Barry’s so-called deception—now it is seen as the “exquisite subterfuge” of an ambitious woman ahead of her time. Today we’re much more inclined to celebrate women who broke barriers, and we even relish the thought of a woman outwitting the sexist establishment that looked down on her. Some historians have called Barry the first woman to become a qualified doctor in the United Kingdom and have placed Barry in the same category as other daring women who had donned men’s clothes to seek their fortunes and serve their countries.

As tempting as this narrative may be, what if it is still fundamentally misrepresenting James Barry’s life and identity?

Barry was most likely born Margaret Ann Bulkley in Cork, Ireland, in 1789. The Bulkleys ran a successful grocery business, but the eldest child, Jeremiah, liked to spend lavishly to impress his rich friends. By 1806 he had bankrupted the family and landed himself in prison. Their luck changed later that year after Barry’s uncle died and left the family a surprise inheritance. With the help of this newfound wealth, in 1809 Barry and his mother set off for Edinburgh. In the early 19th century, Edinburgh was the place to be for anyone wishing to study medicine—the university there was considered the finest medical school in the United Kingdom and one of the best in the world. In Edinburgh, Barry could begin a new life. He enrolled in medical school, and after graduating and passing his examinations for the Royal College of Surgeons, he joined the army. His career lasted 50 years and was spent in outposts across the British Empire, from South Africa, to the Caribbean, to Canada, and nearly everywhere in between.

Slight of stature and known for a love of flamboyant clothes and stylish wigs, Barry’s dapper appearance belied a toughness and a hard-nosed, often belligerent dedication to his job. (He was known also to carry a rapier.) He had a habit of infuriating people in power in his quest to improve sanitation and medical care in the communities he served. As the medical inspector in Cape Town, South Africa, he cracked down on quack-medicine hawkers, worked to improve access to clean water for rich and poor alike, and drew up strict rules for the humane treatment of patients at a local leper colony. He also performed one of the first documented cesarean sections in which both mother and infant survived.

Barry took this same crusading spirit to other outposts of the British Empire. While stationed in Canada, he demanded that the living conditions and diets for soldiers be improved and that all ranks have access to recreational facilities and libraries. He had a reputation for shouting, swearing, and insulting those who got in the way of what he saw as necessary reforms, shocking even Florence Nightingale with his brutish nature. As one observer later put it, “Although it is quite certain that for these ‘interfering ways’ many of the senior officers disliked Barry, there must be still many officers and a great many of the ex-rank and file who remember [him] with gratitude.”

By 1859 the 70-year-old Barry’s health was failing. He returned to England, where, over his objections, the medical board forced him to retire. He died a few years later, leaving behind a remarkable professional legacy and a simple request: that his body remain unexamined after his death and that he be buried in the clothes he was wearing when he died. Had that request been followed, Barry likely would be dimly remembered today for his crusading medical work. Instead, people have spent the last century and a half hypothesizing about his gender—speculation based not on how he lived, but on the nature of his body when he died.

Today we might call Barry a trans man: someone who was assigned female at birth but who identified as a man and transitioned their name and appearance to align with that understanding of themselves. Barry could not have used the word trans to describe himself—it was first used in this context in 1974—but his story has many elements that transgender people today might find familiar. As historian David Obermayer observed, “My experiences allow me to see a kinship with Barry’s identity and his struggle, particularly at the end of his life, to make sure that identity was respected.”

Yet most historical accounts still refer to Barry as female, placing him in a category much beloved in the popular imagination: that of the woman who dresses as a man to chase fortune or love. It’s a very old, sometimes apocryphal, tradition that includes 6th-century Chinese legend (and modern-day Disney hero) Mulan as well as the protagonists of “Sweet Polly Oliver” and other broadside ballads from 16th- to 19th-century Britain. In these traditional songs and their modern interpretations, women dress as men to join their true loves at sea or on the battlefield. Historians, such as Peter Boag and Catherine Baker, have pointed out that, in reality, women who cross-dressed probably had more practical reasons for doing so. For example, a woman might have dressed as a man in the 19th-century American West to travel safely, or in 17th-century England to support her family after her husband’s death.

Eighteenth-century botanist Jeanne Baret combined these romantic and pragmatic motivations. In the 1760s, her lover and fellow botanist, Philibert de Commerson, was given a job as a plant collector on a scientific sailing expedition. The pair quickly decided that Baret should join him as his “assistant,” a move that would allow them to stay together and give Baret an opportunity to pursue her scientific passion. She bound her chest in linen, donned breeches, and joined the ship’s crew as a man named Jean. Over the next two years she circumnavigated the globe in disguise, collecting botanical samples all the while. Most notably, she was the first European to discover the bright pink bougainvillea in Brazil, which she named after the captain of the ship, Louis Antoine de Bougainville. The ruse was eventually discovered, though, and the couple were left in the French colony of Mauritius, where they married. Baret went back to living as a woman for the rest of her life.

Like Baret, many of those assigned female at birth who later dressed as men did so for a short time only. They returned to their lives as women when they could support themselves again, were no longer in physical danger, or could be reunited with their loved ones. In these instances, historians usually lack a clear basis for judging how a person might have self-identified. Some of these “cross-dressers” may have, in fact, been trans in the contemporary sense, even if they did not spend the majority of their lives living as men. Others may have unquestionably identified as women, seeing their cross-dressing as merely a short-term solution to a serious problem.

Presented with only the vague sketch of a person’s life and no record of their thoughts or emotions, diligent historians grapple with which pronouns and gender categories to bestow on people who can’t be asked how they identified. “I tried to choose terms that conformed to what I reasoned the person I was writing about would have wanted,” writes Boag in his exploration of cross-dressing in the American West. Boag ultimately found that he had to do “what all historians do at some point or another, taking a leap of faith and hoping the evidence is there to support one’s landing.”

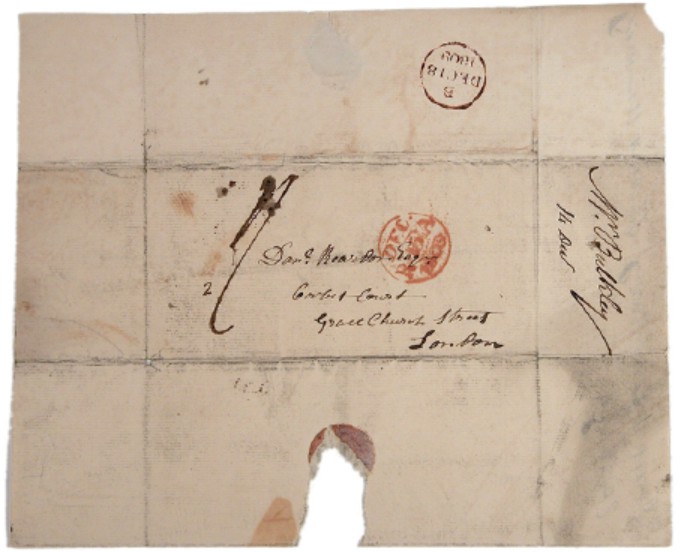

In sharp contrast, though, Barry’s story presents no such ambiguity. The very last mention of Margaret Bulkley in the historical record appears in a letter Barry wrote to the Bulkley family solicitor shortly after settling in Edinburgh; though the letter was signed James Barry, the solicitor wrote “Miss Bulkley” on the envelope, as if reminding himself that Barry and Bulkley were the same person. Barry never returned to his previous name and never presented as a woman again, living both publicly and privately as a man, signing his letters as a gentleman, and using male pronouns to describe himself. In his medical school thesis he tellingly wrote, “Do not consider whether what I say is a young man speaking, but whether my discussion with you is that of a man of understanding.”

Yet many historians, including multiple biographers, still assert that Barry was a woman who tricked everyone. This emphasis on the gender Barry was assigned at birth and fascination with his so-called subterfuge parallel the ways trans people are often discussed outside of history books. The idea that a trans person isn’t really who they say they are is built into a lot of anti-trans rhetoric, both subtly and unsubtly. It shows up in popular film representations, where trans women are still depicted as unstable murderers, men in dresses, or as a shocking punchline. When people advocate for so-called bathroom bills that would force trans people to use the restroom that matches the gender they were assigned at birth, or when organizations argue that trans men suffer from “internalized misogyny,” they are essentially claiming that trans people are lying about who they are.

This perspective on trans identity isn’t just offensive—it literally gets people killed. Cisgender men who have attacked and killed trans people will often claim that they were provoked into doing so by the realization that the victim, usually a trans woman of color, was “lying” about their gender. While such murderous acts may make a historian’s speculation seem of little consequence, both stem from a fundamental rejection of a trans person’s clearly stated identity. Whether the response is a criminal act, a cruel joke, or—in the case of so many historians who have written about Barry—a condescending dismissal, these claims of subterfuge and trickery show an unwillingness to imagine trans people as people and fully worthy of respect.

For his entire adult life, James Barry gave no indication that he was anything other than a man. Let’s take him at his word.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated Barry’s branch of military service.