Praise from Fritz Haber was high praise indeed. So people listened when the man who won a Nobel Prize for turning air into fertilizer wrote, “Max Albert Bredig rates among the most intelligent and best-trained young colleagues I have met. Not easily will anyone be found who surpasses him in industry and thoroughness, good will and professional interest.”

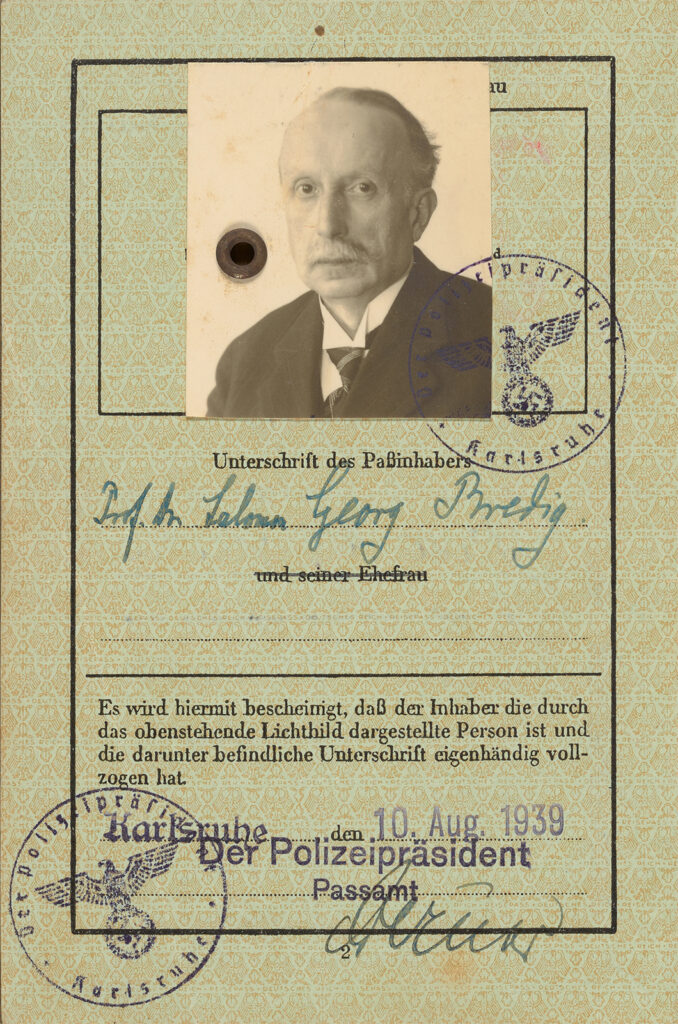

The 24-year-old’s path into the German chemical industry seemed already paved, following that of his father, Georg Bredig, a well-known professor and scholar of physical chemistry who himself had trained under some of Europe’s greatest chemists. Georg provided Max with the foundational knowledge to be an outstanding physical chemist, but it was in Berlin, under the tutelage of Haber, that Max engaged with the world’s most renowned scientists, including Albert Einstein, Max Planck, Erwin Schrödinger, and Eugene Wigner. In late-1920s Germany, Max’s future seemed bright indeed.

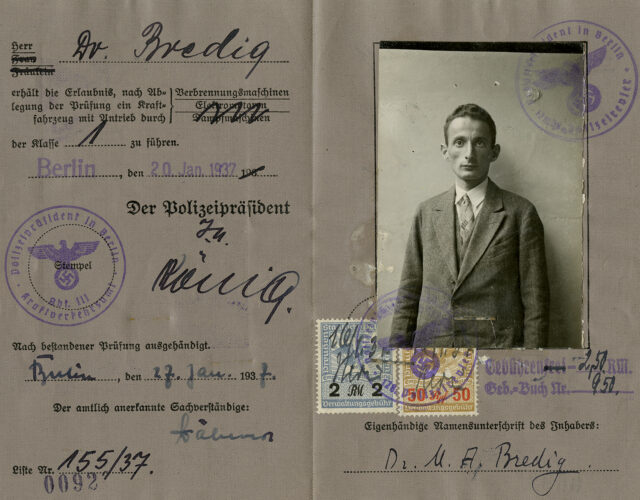

Max Bredig was born in 1902 and raised alongside his younger sister, Marianne, in Karlsruhe, where his father served as the director of the Institute of Physical Chemistry at the Technical University of Karlsruhe. Showing an early aptitude for physical chemistry, Max began his training under his father at the university. Georg went out of his way to avoid any appearance of nepotism as his son’s instructor, even refusing him an assistantship despite his qualifications. Max earned the equivalent of a master’s degree in 1925 from Karlsruhe and received his doctorate in 1926 under the direction of Haber, a friend and colleague of his father’s, at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin.

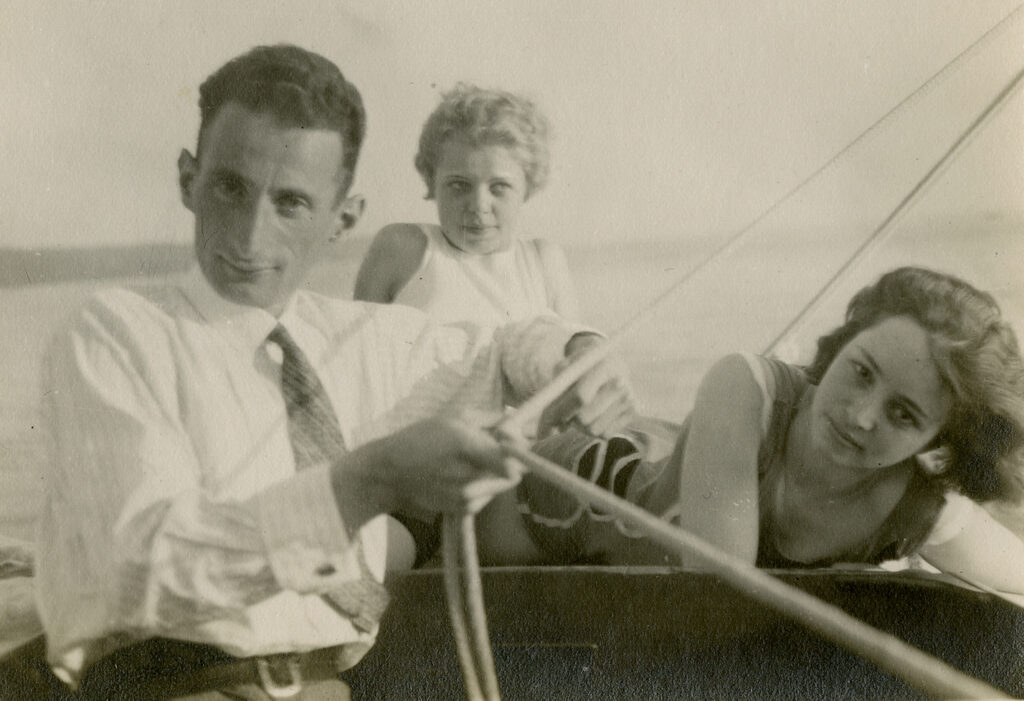

Armed with Haber’s recommendation, Max obtained employment as a research chemist at the Bavarian Nitrogen Works. These were halcyon days for Max, who oversaw the company’s X-ray and optical division and spent his free time sailing, hiking, and playing the piano. But Max’s good fortune began to turn once the National Socialists seized power in 1933. He, like all Germans of Jewish heritage, increasingly became the target of anti-Semitic attacks. In the short term, Max’s position at the Bavarian Nitrogen Works was secure, but others close to him were hurt, including his father, who was forced into an early retirement after the Nazi government banned Jews from teaching at German universities.

Each day seemed to bring a new indignity, as the Nazi regime continued to strip away rights from German Jews until only their citizenship remained. Then the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 took that away.

At the Bavarian Nitrogen Works, Max’s colleagues warned him that the firm would soon be aryanized and that he would lose his job. Max took the warnings seriously and prepared to flee Germany. He asked his father to join him in emigrating, but Georg refused, still hoping for a return to the Germany he had loved. Nonetheless, he encouraged his son to leave.

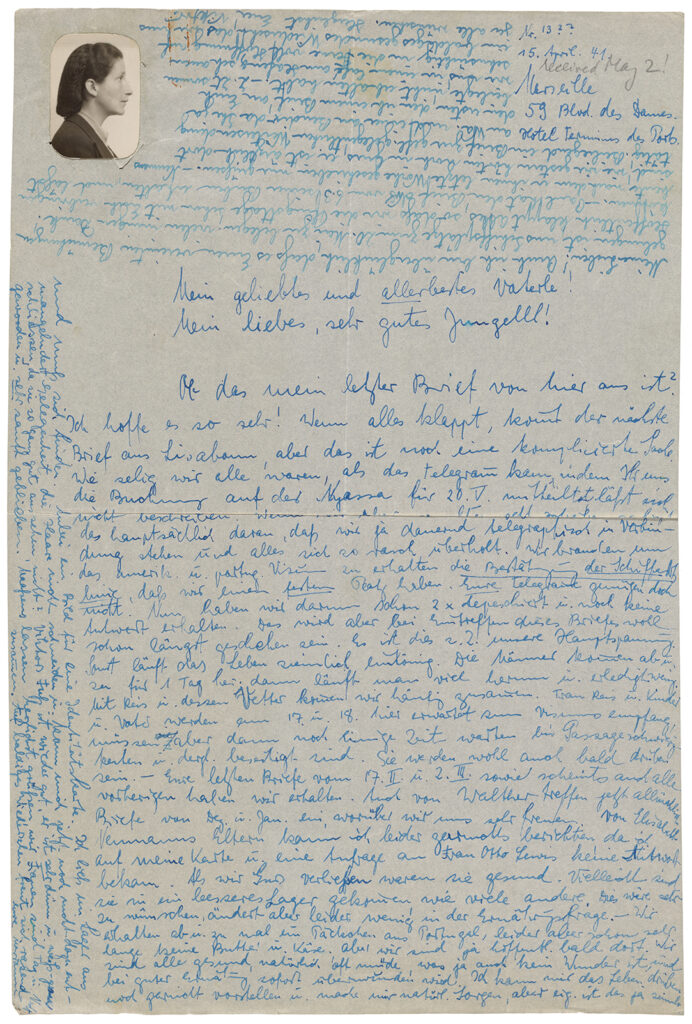

Max fled in 1937, travelling first to Sweden, and then to England, before finally arriving at the University of Michigan’s Department of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering, where he had been offered a fellowship. Having landed safely, his thoughts now turned to those left behind. He corresponded frequently with his father and sister and encouraged them to leave Germany and join him in the United States. Both Georg and Marianne were reluctant to leave. Marianne had just married and was raising three stepchildren. She was also unwilling to leave her father behind. “My biggest worry these days is dad,” she wrote Max. “Although he is healthy, he is very sad, and of a sadness that is difficult to cure. . . . I do not want to separate from him.”

But then came Kristallnacht, a pogrom that hit the city of Karlsruhe particularly hard. Georg, his son-in-law Viktor Homburger, and about 500 other Jews in the city were arrested, beaten, and publicly humiliated. Viktor’s family bank was ransacked and later confiscated by the state. Although Georg was released the following day, Viktor was sent to the recently opened Dachau concentration camp, where he was imprisoned for six weeks and released only after proving his intention to emigrate.

After Kristallnacht, it was no longer a question of whether to leave Germany, only how to leave. Viktor and his family were in line to get American visas, but with so many people trying to immigrate, it would be years before their turn came. Certain that conditions in Germany would worsen, Marianne insisted her three stepsons be sent out of Germany as quickly as possible. Peter, Wolfgang, and Walter, ages 10, 12, and 14, respectively, travelled to England as part of the Kindertransport, in which 10,000 Jewish children were taken in by families across the United Kingdom.

The events of Kristallnacht also convinced Georg to leave Germany. He made it to the Netherlands in 1939, but it was then up to Max to get him across the Atlantic. Max set out to secure his father a teaching position at an American university—only with that in hand could Georg obtain a coveted visa. Princeton University responded with a pro forma position of research associate, with a salary that was to be funded entirely by Max. Georg, thrilled and relieved to receive the appointment, replied to Princeton’s president with a short and succinct telegram: “Highly honored. Accept. Coming as soon as possible.” He arrived in the United States just months later.

Max also labored to bring Marianne and Viktor to the United States, although this task proved far more challenging. In October 1940, the couple, along with 11,000 other Jews from the Baden region of Germany, were forcibly deported to Vichy France. They were brought by train to Lyon, and then sent to the Gurs internment camp, built years earlier for refugees of the Spanish Civil War.

The French running the camp were not nearly as cruel as their Nazi counterparts, but they had no means to help the 11,000 people in desperate need of food, water, and clothing. At first the camp was only loosely a prison—individuals were permitted to leave for the day to obtain food and other essentials. Marianne used this time to visit Viktor, who was kept in a separate camp for men, and to send letters to Max, who was working to secure immigration visas.

The archives at the Science History Institute hold many letters written by Marianne while she was interned at Gurs. “As long as the sun shines, it is bearable here,” one early letter reads. “If it rains and gets cold, it is quite terrible. What people here are suffering cannot be expressed. The poverty is unbelievably huge.” She continued,

Max was able to arrange shipments of food and clothing to the camp. He wired cash payments to a contact in Portugal, who would in turn send shipments of nonrationed dry goods to Gurs. Money was also sent to bribe local officials and anyone else who could assist in securing Marianne and Viktor’s release.

Eventually Max did secure the visas, transit permits, and transport necessary to rescue his sister and brother-in-law from the camp. In a letter announcing his success, Viktor wrote,

Viktor and Marianne were among the lucky ones. Of the 11,000 Jews evacuated from Baden and sent to Gurs, only about 1,000 were released. Approximately 1,000 others would die in their first winter; most of the remaining 9,000 were sent to extermination camps in Poland and never heard from again.

With his family safe, Max pressed on, working to get Jewish colleagues out of Europe. He had several successes, such as chemists Alfred Reis and Fritz Hochwald, but despite his best efforts, Max could not save everyone.

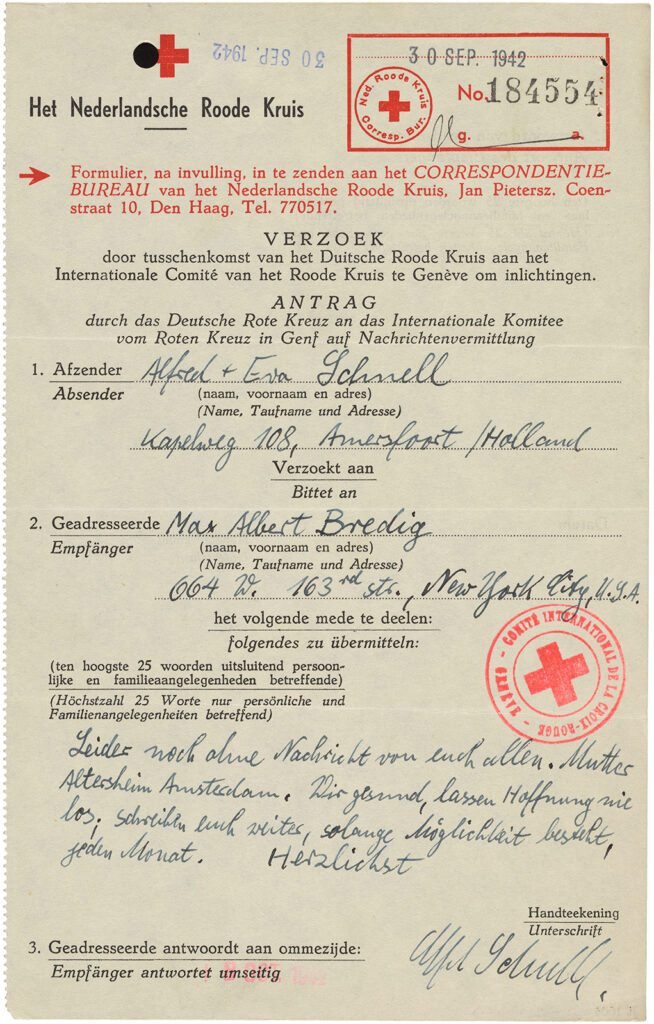

In 1938 Max’s former colleague Alfred Schnell married Eva Jolowicz, a primary school teacher from Homburg. The two then fled Nazi Germany to escape the persecution of Jews and took up residency in The Hague. When Germany invaded the Netherlands, life again became increasingly difficult. In 1943 they were ordered to report to a Nazi transit camp, but instead they went into hiding.

Their search for a suitable hiding place brought them to Otto Veening, a pastor and member of the Dutch resistance movement. Veening had created a network of hiding places in the countryside for Jews and young Dutch men who wished to avoid slave labor in German factories. With his assistance, Alfred and Eva were placed on a farm in Oldebroek, about 40 miles east of Amsterdam, with a widow named Hendrikje Blaauw-Flier.

While in hiding they sent short messages to Max through the Red Cross. Often writing in code and using aliases to protect their identities, these letters were their only lifeline to the outside world.

In autumn 1944 Max lost contact with the Schnells. According to eyewitness accounts, the Schnells were arrested by the Germans during a raid of the surrounding area. The couple were found in their hideout under a haystack and taken to a nearby town for interrogation. They were to be kept overnight and transported the following morning to Poland. But that night a pair of Dutch Nazis took Eva and Alfred from their cells, along with four other prisoners. They were taken to a park and told to dig six holes. When Eva protested, she was shot. The rest were murdered immediately after.

Max learned of the Schnells’ fate from a letter he received just after the war. Wim Wesseldy, who had been in hiding on a farm in the same area, gives a detailed description of the Schnells’ last 18 months and tells of the friendship he forged with the couple. The following is a small portion of that letter.

He describes how he came to meet Alfred and Eva and writes about their living conditions:

He continued:

Eventually, I came to spend nearly every evening with them and we became very good friends. They helped me a great deal with their friendship at a time when I had many difficulties. Often, we imagined how we should visit one another and stay with each other when peace and normal life, for which they were longing so much, should have returned. Our dreams will never come true.

Frequently, I am likely to ask, why they had to die, who so rightly deserved to have lived to see better times. I do not know the answer. The only thing I know, from experience, is that God loves me even when he seems to be chastising me. Rest assured that Eva and Fred will live forever in my memory. I am grateful that I have known them.

In 2001 a monument was unveiled honoring the six people murdered on the evening of October 3, 1944. A nearby primary school has adopted the monument, which is located in the park where the six were murdered. Students take care of the monument’s upkeep and take part in a memorial ceremony each year.

Such losses affected Max deeply. After the war he made a point of identifying former colleagues sympathetic to the Nazi regime. Of Wolfgang Ostwald—the son of his father’s mentor—he wrote,

Max would go on to scorn invitations from German universities and scientific societies that sought to welcome back German Jewish scientists after the war.

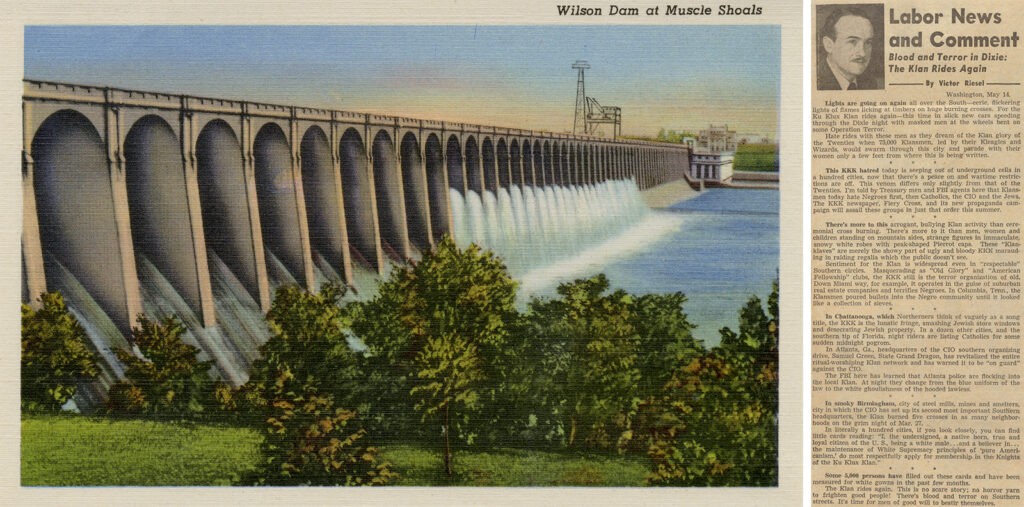

He also leveled a disdainful eye on the injustices in his adoptive country. In 1946 Bredig was offered a job with the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in Florence, Alabama. He was wary. After meeting Bertha Klenova, a fellow European immigrant employed by the TVA, he wrote to her with questions about the cultural climate in Alabama and about anti-Semitism within the TVA and surrounding area. Klenova’s response was withering:

Accompanying the letter was a newspaper clipping headlined, “Blood and Terror in Dixie: The Klan Rides Again.” The story describes, among other things, how the KKK smashed the windows of a Jewish store and desecrated Jewish property. It’s little surprise Max declined the TVA’s offer.

Max and his wife, Lydia, who he married in 1944, had one son, George. In 1946 Max was hired by Eugene Wigner, an old Berlin colleague who had become the director of research and development at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Max worked at Oak Ridge until his retirement in 1967 but stayed on as a consultant until his death, on November 21, 1977.

Today Max is remembered as a first-rate scientist. He published approximately 100 scientific papers and is probably best known in the field for his work on the interaction of molten metallic halides with their metals. The mineral bredigite, Ca7Mg(SiO4)4, was named in his honor for the work he did studying it. To this day, the Max Bredig Award is given out by the Electrochemical Society.

Still, few people know about the work Max undertook during the war. He rarely spoke of the hardships he and his family endured during the Nazi regime or his efforts to save family, friends, and strangers. Whether it was an unwillingness to relive painful memories or just personal modesty, even some members of his family never knew of Max’s wartime activities until after his death, when the contents of his archive surfaced. We now know that Max made the lives of others his personal responsibility and did so with no thought of praise or thanks but merely because it was the right thing to do.