Why do we still talk about Louis Pasteur?

It’s been 200 years since the pioneer of germ theory and modern vaccines was born, and still his reputation endures. Though he never visited the United States, the Frenchman’s memory has persisted here not only among natural scientists but with the general public as well. But why? What made him more memorable than so many other worthy scientists of the past?

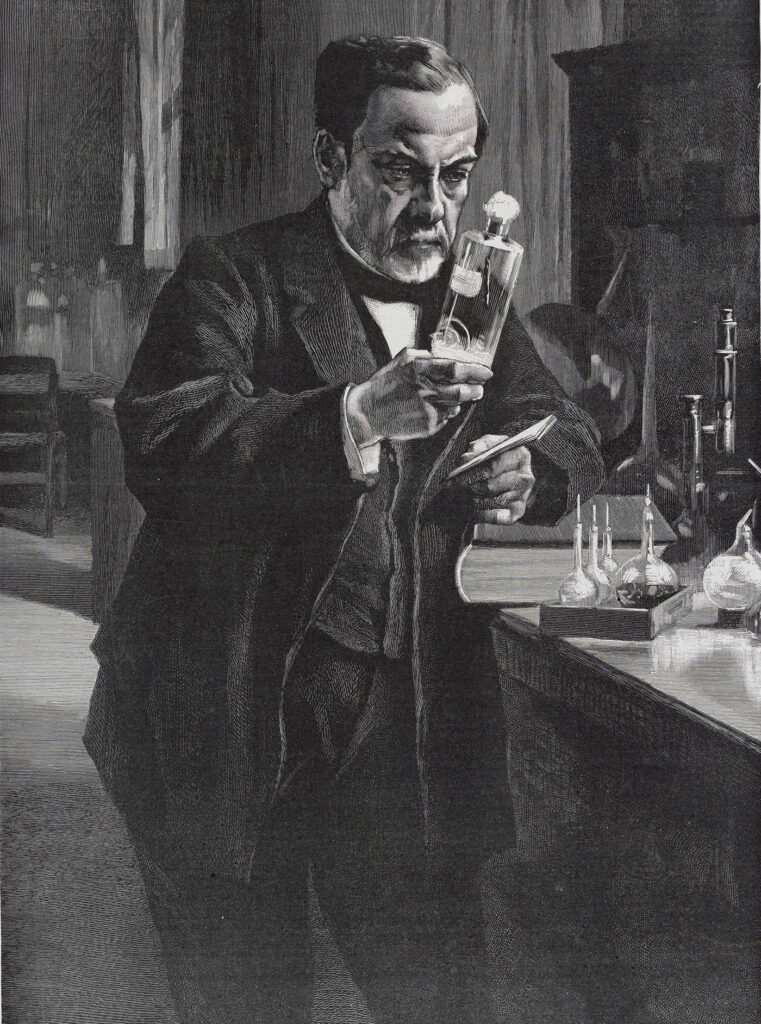

Reproduction of Edelfelt’s famous Pasteur portrait as it appeared in Harper’s Weekly, 1885.

Pasteur’s legacy is built in part on a foundation he engineered himself. Well before other scientists recognized the value of fame, Pasteur cultivated relations with popular magazines and daily newspapers, and he worked closely with artists and photographers to create and guide favorable images into the press. Such initiatives had no precedent in science. Instead Pasteur took inspiration from friends in the art world, including William Bouguereau, Jean-Jacques Henner, and Paul Dubois, and closely followed reviews of the annual Paris Salon. He observed firsthand how artistic success depended on press coverage, often writing his friends about their reviews, both favorable and not.

Coverage of Pasteur’s practical achievements helped guarantee the government’s support of his research, and public familiarity helped ensure his innovations for industry, agriculture, and human health would become more than dusty reports on library shelves.

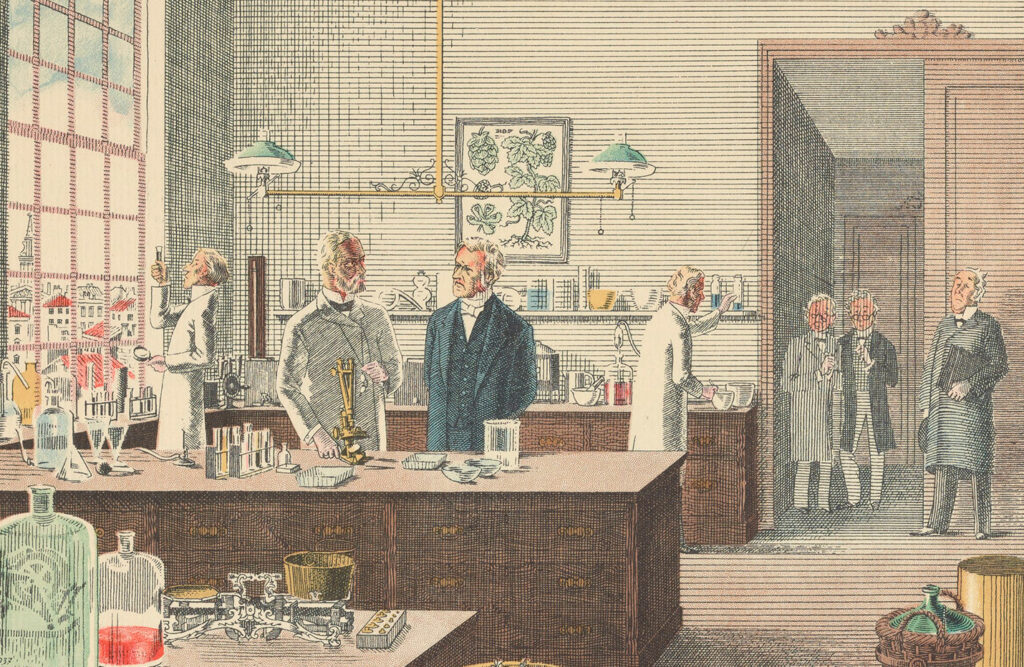

Cultivating ties to industry bolstered Pasteur’s reputation as well. Early in his teaching career, the chemist took on new questions industrialists brought to his attention. He began applying techniques from basic scientific research to solving a series of real-world problems. In time, he moved from puzzles in alcohol and vinegar production to a study of the microscopic and unnoticed living organisms in the air. He was able to demonstrate that these invisible life-forms caused both useful fermentations and spoilage and decay; he dubbed them microbes. He imagined that such living “germs” rode on dust particles—even in apparently clean air—and were the source of the wound infections that killed so many people after serious injury and surgery. English surgeon Joseph Lister used this notion, fully credited to Pasteur, to develop antiseptic treatments for surgical wounds and eventually aseptic operative techniques that saved countless lives and established the first formulation of germ theory.

Pasteur consulting for London’s Whitbread’s Brewery in 1871. Engraving by Mark Severin, 1937.

Gradually, Pasteur’s research moved from chemistry to biology and the medical realm, where he achieved breakthrough results in immunizing animals and humans against certain infectious diseases. He defined these immunizations as a general process he named vaccination to honor Edward Jenner’s cowpox vaccine, the only such procedure before Pasteur’s vaccines for fowl cholera, anthrax, and the dreaded hydrophobia, or rabies.

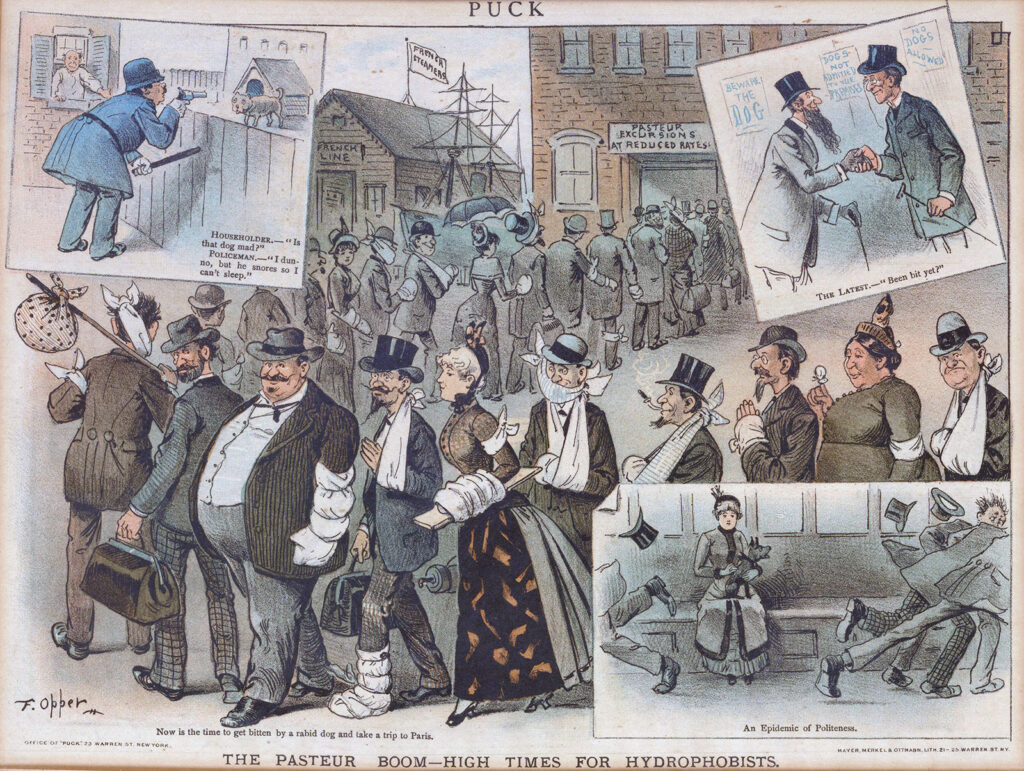

Pasteur’s rabies shots were a perfect story for the international press in 1885 and made sensational headlines everywhere. Reporters and illustrators followed the throngs of new patients into his laboratory. He made time for both kinds of visitors. Pasteur shared a laugh with the Paris correspondent of the New York Herald, who brought him a new issue of Puck magazine with a caricature titled “The Pasteur Boom—High Times for Hydrophobists. Now Is the Time to Get Bitten by a Rabid Dog and Take a Trip to Paris.”

“The Pasteur Boom—High Times for Hydrophobists,” from a December 1885 issue of Puck.

With the breakthrough rabies vaccine, Pasteur no longer needed to hustle his likeness into the daily press, but he still worked to sustain his visibility in popular culture and high culture alike. He carved out time to sit for many paintings and sculpted busts. He was often active behind the scenes in burnishing his reputation, working closely, for example, with his son-in-law on a book-length biography that appeared in 1885, though neither of their names appeared on the title page.

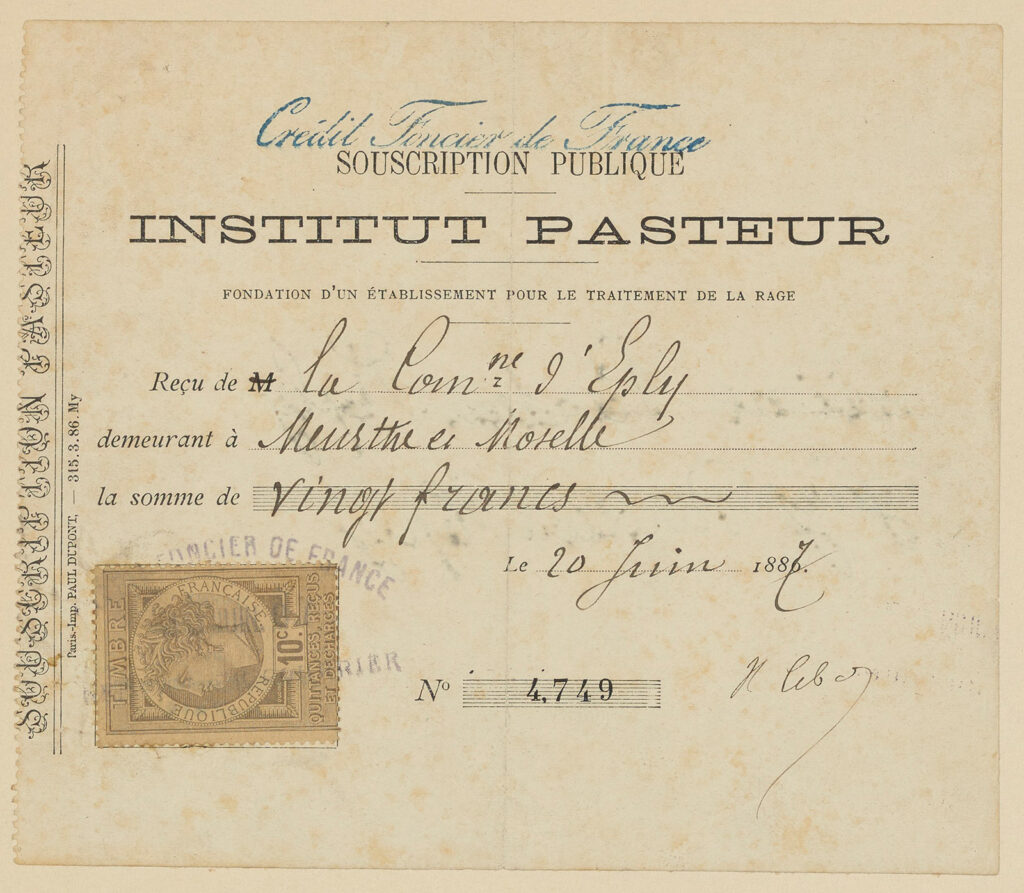

Receipt from the Pasteur Institute to the small community of Éply in the Lorraine region of France, June 1887.

Pasteur’s work had often been awarded scientific prizes, but after the success of the rabies vaccine the scale of his honors grew several-fold. The Pasteur Institute in Paris opened in 1888 with small donations from tens of thousands of ordinary people, millions of francs from business and banking families, and special gifts from the czar of Russia, the sultan of Turkey, and the emperor of Brazil. At a celebration of Pasteur’s 70th birthday held at the Sorbonne in 1892, he was escorted to the dais by the French president to the applause of 400 dignitaries.

At his death in 1895 Pasteur was given a state funeral but was not buried in the Pantheon, where many of France’s cultural heroes are enshrined. His family instead constructed a chapel-like crypt beneath the Pasteur Institute and decorated it with neo-Byzantine mosaics, thereby treating him like a saint and turning the Pasteur Institute campus into sacred ground. Cities around the world responded in the decades that followed, erecting memorial statues and monuments, which kept his image in the public eye.

In the United States, Pasteur’s writings had made him known first to scientists and physicians. But his fame as an innovator and a miracle worker was widespread among the general populace. As early as 1869, a California winemaker’s letter to the editor claimed that “Pasteur is as popular amongst the viniculteurs as the President of the United States; and if he were here they would elect him to high office.”

Statue of Pasteur by Laurent Marqueste at the Sorbonne (left) and the interior of his tomb at Pasteur Institute (right), from a series of postcards, ca. 1920.

Pasteur became a household name in 1885 when his new rabies shots saved the lives of four American children rushed to Paris for treatment. After his death he was widely memorialized in the American press, with large images and major tributes in a diverse range of venues, from Harper’s Weekly and the Literary Digest to The Household, a monthly magazine devoted to “the interests of the American housewife,” where his photograph was captioned, “The Famous French Chemist, One of the World’s Practical Benefactors.”

Pasteur’s practical discoveries made him an agreeable hero to Americans steeped in “can-do” culture and prompted posthumous celebrations of his career. But unlike in France, where the Pasteur Institute has acted as a powerful lobby for Pasteur’s remembrance, American recognition has been as eclectic as it has been common over the past hundred years, with a variety of independent enterprises calling on his story to serve their purposes, guaranteeing that his name and work have remained familiar on this side of the Atlantic.

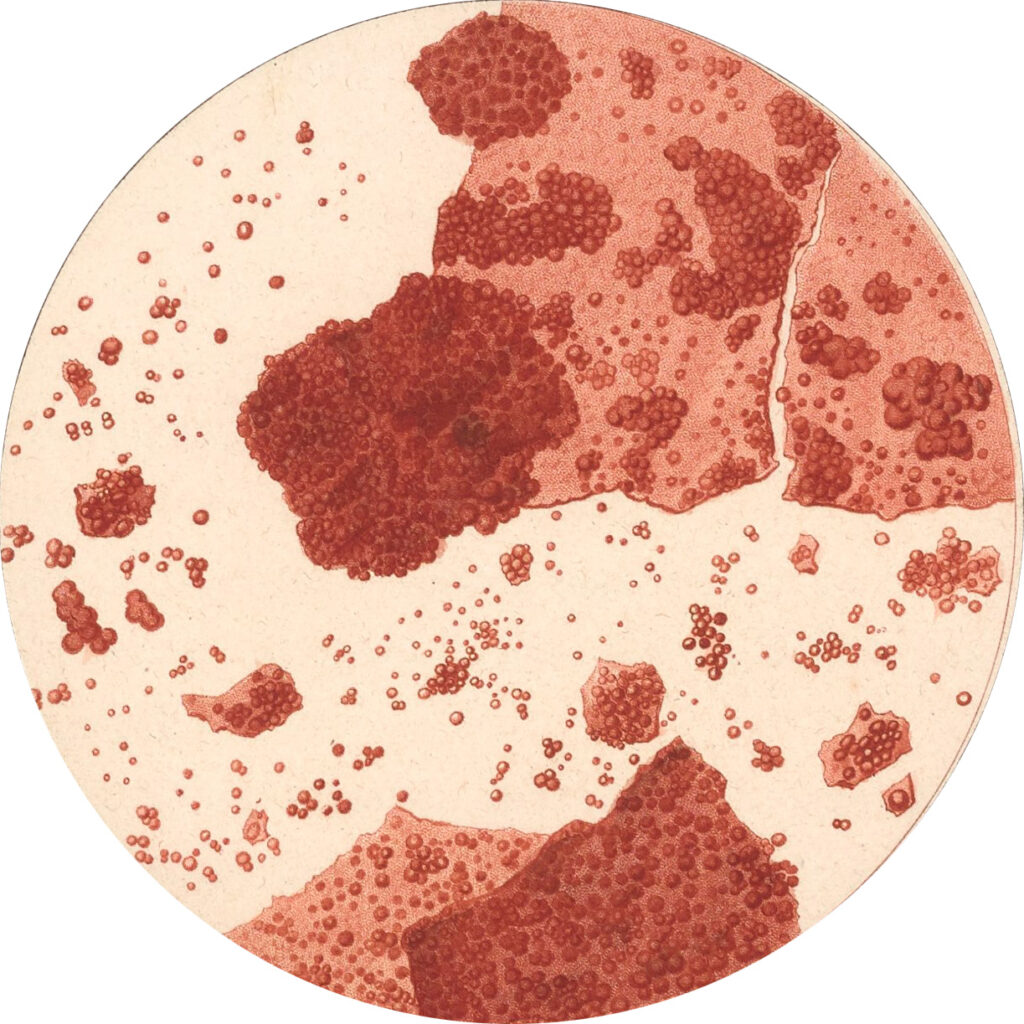

Microscopic view of healthy wine, from Pasteur’s investigations of wine diseases, Études Sur Le Vin (1866). Illustration by Pasteur’s regular artistic collaborator Peter Lackerbauer.

Early in the 20th century, American repute for Pasteur received a boost when the oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller, guided by his adviser Frederick T. Gates, established the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in 1901 to emulate the revolutionary, laboratory-based medical research being done at the Pasteur Institute. In 1912, when Rockefeller heard the town of Dole was trying to preserve the house where Pasteur was born to establish a museum, he bought the building and gifted it to the town, freeing up local donations to maintain the museum.

Poster advertising an exposition commemorating Pasteur’s centennial in Strasbourg, France, 1923.

Anticipating the 100th anniversary of Pasteur’s birth in 1922, American scientists and public leaders planned speeches, conferences, and exhibitions in several cities, with a national celebration in Philadelphia. In addition to talks by leading scientists, messages were read from President Warren Harding, Chief Justice William Taft, and former President Woodrow Wilson. The afternoon session aired nationally on the Wanamaker Radio Broadcasting Station.

France celebrated this centennial with a variety of publications and special events, some of them linked to the United States. Notably, at the University of Lille, where Pasteur held his second university post, a dean from the University of Pennsylvania’s Towne Scientific School was presented with several pieces of original glassware from Pasteur’s years in Lille’s chemistry department. These were not personal souvenirs, but quasi-sacred relics of Pasteur’s life, destined for sanctified display in seven American universities.

In 1926 a new popular book thrilled readers with the breathlessly recounted adventures of researchers in medicine and the life sciences. Paul de Kruif’s Microbe Hunters was a hit and has remained in print for nearly a century. Pasteur was the only figure given two chapters in this book, which dozens of prominent scientists have claimed as key inspiration in their youth. In 1996 the editor of New Scientist observed that the 70-year-old book “must have drawn hundreds of thousands of young people into either biology or medicine.”

Publicity still of actor Paul Muni reenacting the famous pose from Albert Edelfelt’s portrait of Louis Pasteur.

A decade later Americans flocked to see a melodramatic biography, The Story of Louis Pasteur. Despite the typical Hollywood mélange of invented subplots, characters, and conflict, the film succeeded in bringing to life many key historic episodes, such as the public demonstration of the anthrax vaccine, Pasteur’s insights about germs living in the air and on people’s hands, the treatment of the first rabies patient, and Pasteur’s birthday jubilee at the Sorbonne in 1892. For the film’s premiere, studio publicists brought over Joseph Meister, Pasteur’s first rabies patient who had been only nine when he received the vaccine. His ship was met by William Lane, one of Pasteur’s four initial American patients. A surprise hit, the film won Oscars for leading actor, best story, and best screenplay.

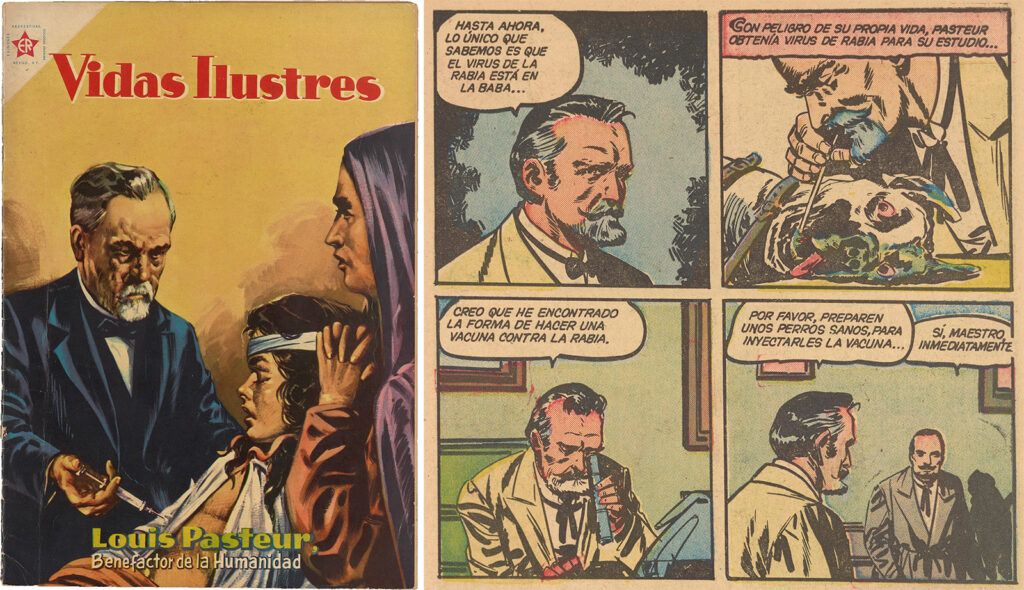

In the 1930s and 1940s, Pasteur also cropped up in several of the era’s popular radio dramas, but his biggest audience came through children’s comic books, a totally new form of storytelling. Beginning in 1937, these cartooned stories of criminals, detectives, superheroes, and funny animals took America by storm. By 1941, historical figures appeared in titles such as True Comics, Real Life Comics, and It Really Happened. Pasteur and disease-fighting U.S. Army doctor Walter Reed each made it into several comics. While sales of these true-adventure books, which averaged about 700,000 copies monthly, couldn’t compete with the millions sold by Superman and Batman, it’s fair to say that these books must have been the most widely disseminated medical history publications of any era.

Cover and panels from theissue #4 of the Mexican comic book Vidas Ilustres featuring Pasteur, May 1956.

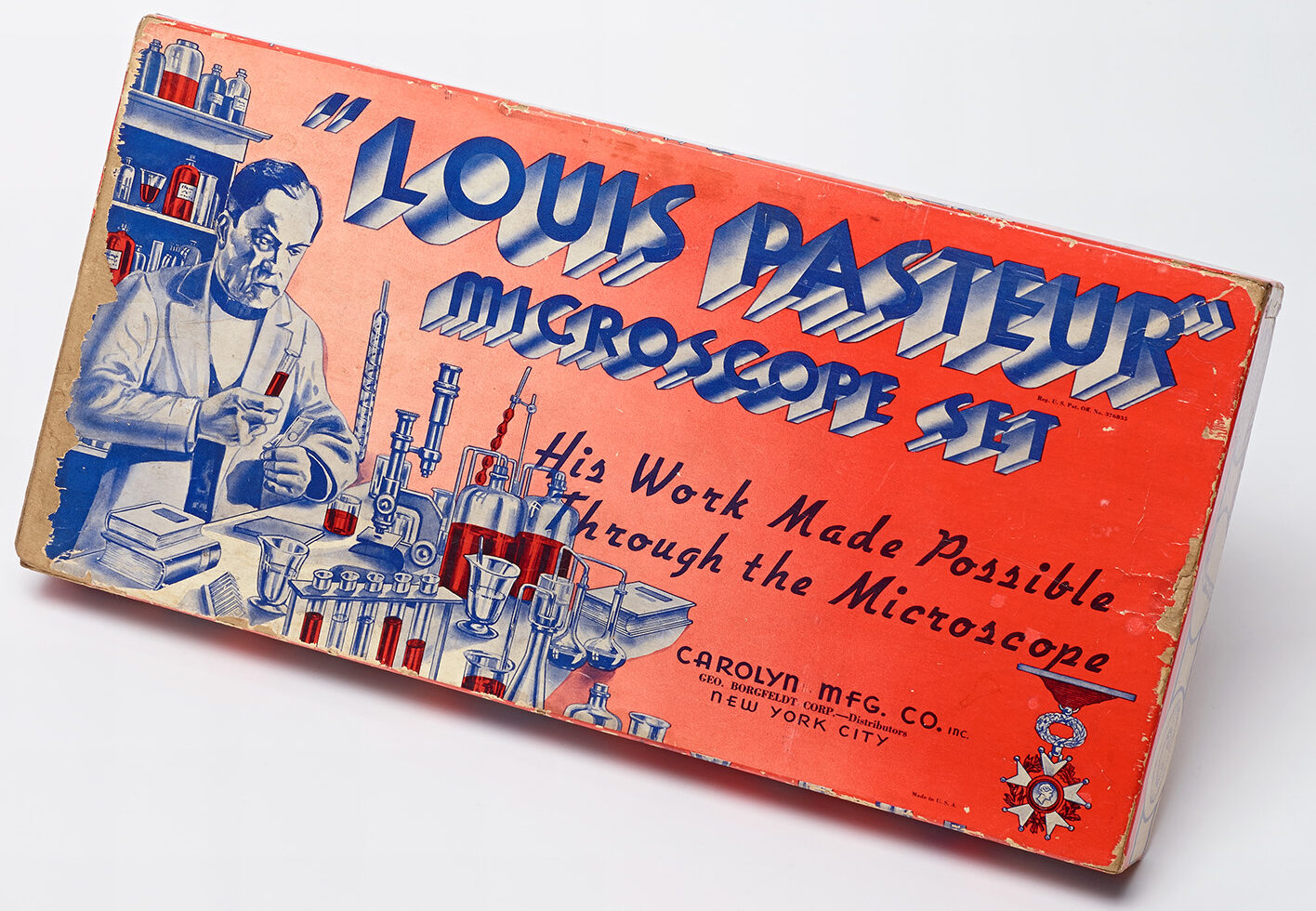

At just the same time, American parents began pressing educational toys on their children, especially boys, to help spark their scientific curiosity. In an image echoing Albert Edelfelt’s famous painting (and scenes from the Hollywood film), Pasteur dominated the vibrant red and blue box of the Louis Pasteur Microscope Set.

These efforts seemed lacking a decade later when the Soviet Union shocked Americans with the successful launch of Sputnik. The National Science Foundation took this as a wake-up call and pressed massive new funding on educators, thereby launching hundreds of initiatives to generate early enthusiasm for science careers among children and teenagers. The NSF funded competitive programs that sent high school students to study science on college campuses.

Lid for the Louis Pasteur Microscope Set, after 1920.

I happened to be one of those high school students in the late 1950s. I spent three summers on campuses, including an eight-week stint in a research laboratory so different from a classroom lab. We were welcomed as peers, not subordinates, but like everyone we were expected to learn techniques quickly and to perform operations, even repetitive ones, with precision and consistency.

A multitude of discoveries in biology and medicine in the 1970s and 1980s opened up unprecedented research areas centered on DNA and computing. Though this new scientific frontier was far distant from Pasteur’s lab-bench physiology and microbiology, his effort to bring lab science into medicine was recognized as a foundation for the new approaches. To mark the 100th anniversary of his death, the French government proclaimed 1995 “The Pasteur Year,” prompting hundreds of events worldwide. Americans sponsored many festivities to honor Pasteur and to celebrate the wealth of scientific developments growing from his work. The Pasteur Foundation in New York took the lead in organizing 90 exhibitions, meetings, lectures, film showings, and TV broadcasts across 30 states, plus Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C.

A display at Yale’s Pasteur at 200.

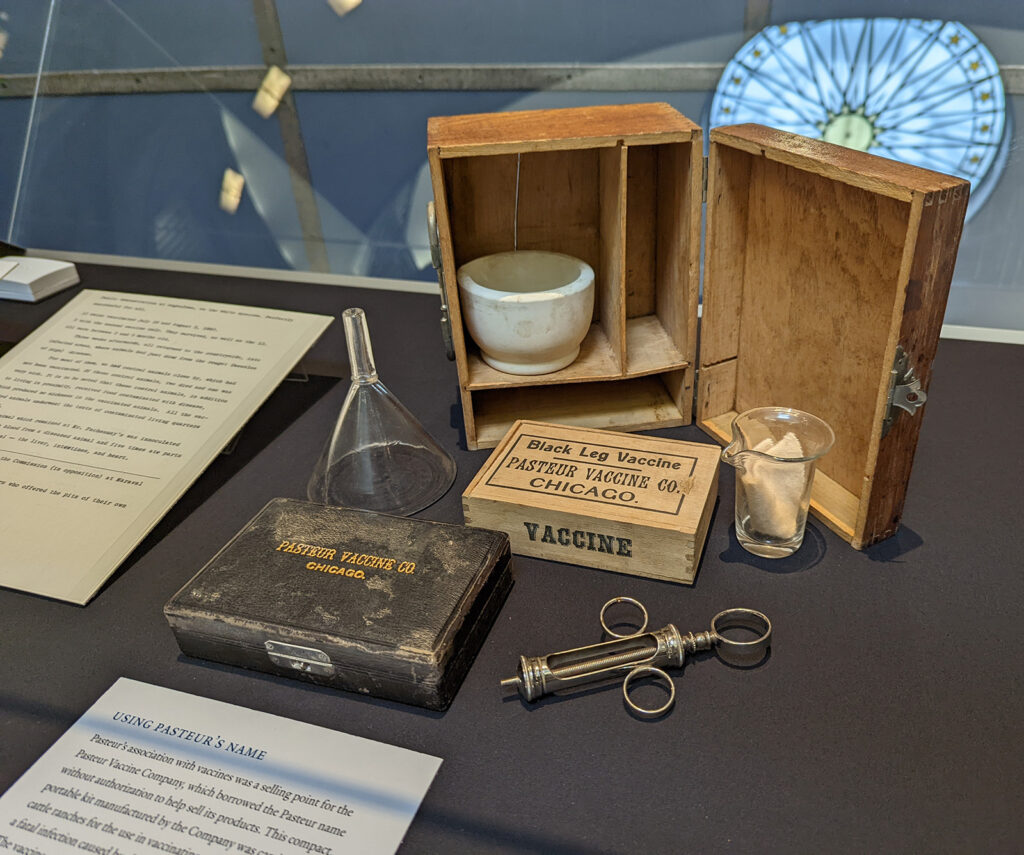

The latest entry among American appreciations is Pasteur at 200, a large exhibition at the Cushing/Whitney Medical Library of Yale University. (I advised the curator on the history of some of the items.) In presenting Pasteur’s investigations of spontaneous generation, fermentation, and vaccines and relaying the legacy of his discoveries and his near-mythic status in France and abroad, the show combines dozens of books and objects from American culture with objects touched by the scientist’s own hand, including a piece of glassware from his lab at Lille University, one of the sacred relics presented to American universities a century ago.

Although about 40 bicentenary activities have been announced abroad, Yale’s exhibition seems to be the only American commemoration. That being the case, it’s natural to ask—will the Yale display mark the end of Pasteur’s reign in American culture?

His prospects are not auspicious. For one thing, history is changing. Science historians have diversified the people we study, emphasizing social dimensions of science and abandoning a presentation of progress as the achievement of elite European men. Without denying Pasteur’s rare ingenuity or his contributions to global health, new approaches mean anniversaries and commemorations will be less common.

Perhaps more importantly, the way we engage with science has shifted as well. Advances in science and changes in science popularization have widened the gap between the sensual experiences of the natural world that laypeople and scientists long shared and the new abstract images and facsimiles that have displaced them. Today we’re more likely to study digitized and mediated models of natural phenomena than the genuine articles. Prior to this divergence ordinary people could both understand the ideas scientists such as Pasteur set forth and appreciate the hard work of manipulating slippery, uncooperative reagents and natural bodies in the laboratory.

Of course, the internal structures of an earthworm are plainer to see in the plastic models often used in today’s classrooms than when revealed via dissection. But without doing it for themselves, students fail to learn the many mundane but consequential difficulties working scientists must overcome. Cooks, craftspeople, and some engineers still know firsthand the unpredictable variability of natural substances and the difficulty of achieving precision. They and those of us who took lab courses several decades ago are better equipped to appreciate the skill of using just fingers and eyes to, say, find the right adjustments of light and focus and the perfect placement of a cover slip over a specimen to reveal microbes or cell parts clearly through a microscope.

Students and the public enjoy a new kind of access to nature at all scales, whether colorful virus particles or distant galaxies. These images feel realistic. Yet by building assumptions into computer algorithms, programmers and graphic designers are responsible for all the colors and many of the shapes. The gorgeous images are not false or fake, but our senses have no other access to the objects depicted. By contrast, with Pasteur’s microscope even the Empress and ladies of her court could see for themselves—in real life and in the Hollywood film alike—the invisible little plants causing diseases of wine.

Empress Eugénie and others take an interest in Pasteur’s microbes in this publicity still from The Story of Louis Pasteur, 1936.

Once science teaching came to be dominated by preternaturally uniform models, mysteriously sourced data, and gloriously clear images delivered on-screen, the world of 19th-century science no longer felt familiar or even real. Neither students nor the general public can connect with Pasteur’s material world like the nine-year-old son of a Warner Brothers studio electrician in 1936 who saw an early screening of the film and asked his father to buy him a microscope.

It is possible that in time we might see a rebound in people’s feel for the physical aspects of the material world that underlie science history. Climate change is expanding everyone’s awareness of the environment. The popularity of unprocessed and local foods is growing. Even the digital technology of easy photography and sound recordings has helped amateur naturalists identify wildflowers or recognize a birdsong from an app. Over time we might recover a feel for the sensuality of physical nature that is needed to appreciate earlier scientists’ heroic struggle to explain the colorful, smelly, textured material world—Pasteur’s included.