During World War II, as American airmen bombed Germany and marines stormed Pacific islands, Disney animators in California were drawing educational cartoons. The company’s beloved characters had been drafted into service, too.

While Donald Duck learned how to file his income taxes in The Spirit of ’43 (“taxes to defeat the Axis”), most of the studio’s work went into creating specialized military-training films. In 1944 88% of the 150,500 feet of film Disney produced went to the highest-tech parts of the armed services: the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics, the Army Signal Corps, and the Army Air Forces. (Disney’s prewar production had been just 27,000 feet per year.) These films, which combined technical drawings with cartoon characters, veered in tone from serious to silly. The drawings were also printed in paper booklets, allowing soldiers and pilots to study in their down time.

Disney’s work was part of an unplanned experiment that spanned the American armed forces. Elsewhere artists put comics to the task of teaching crews how to maintain guns and pilots how acceleration and oxygen deprivation affected their bodies during flight.

Military training is just one example of how comics have been used in informal education for generations. But despite having taught us scientific principles and helped us understand the weather, comics have maintained a persistent reputation for being crude, cheap, and unsophisticated, if popular and fun. Advocates for comics have never been able to shake the vague suspicion that someway, somehow, a medium like that can’t possibly be good for serious learning.

Americans first learned to love comics by reading the newspaper. American publishers, hoping to duplicate the success of Punch and other British comic weeklies, began introducing comic art into their papers in the late 1870s. The arrival of the newspaper comic strip in the 1890s made comics a cultural and financial phenomenon.

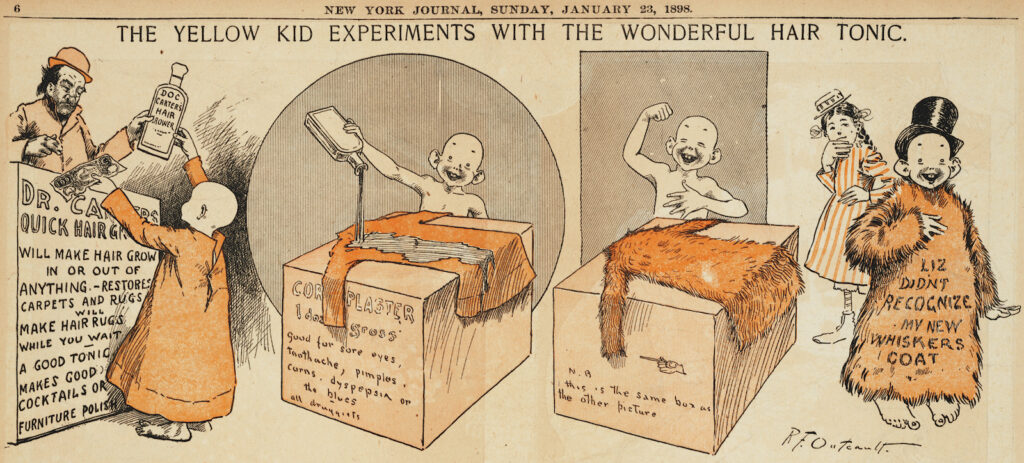

The most notable early example of this success was the Yellow Kid, a character created by Richard Outcault, who had previously worked as a technical illustrator for Thomas Edison. (The popularity of Outcault’s character and his signature color spawned the term yellow journalism for the sensationalist, sometimes fabricated news that accompanied the cartoons.) Comic strips became powerful weapons in the sales and circulation battles between Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Morning Journal. In experiments, one newspaper removed sections and tracked complaints: 88% of its subscribers complained when they didn’t get the comic section, while only 4.5% complained about a missing news section.

Cartoon characters soon became valuable commercial properties. Competing newspapers poached cartoonists and their strips from each other, while cartoonists began to license their characters for commercial use. The Yellow Kid, for instance, had his own line of chewing gum, toys, even cigarettes. But no strip was attached to more products than another Outcault creation, Buster Brown. The strip’s characters would become the mascots for a line of popular children’s footwear and serve as the basis for a Broadway production, films, and radio and TV shows. For his part, Outcault maintained a sense of humor about the mania for his comic. In one cartoon Buster looks across a Christmas scene littered with 21 different Buster Brown–branded products and asks, “My! Is it as bad as that?” His dog, Tige, replies, “Santa Claus ought to pay you a royalty, Buster.”

The popularity of comic art continued to grow in the decades that followed. A 1930 survey by George Gallup made clear that comics were the most read part of the newspaper across demographics. They were loved by laborers and doctors, factory workers and engineers. Advertisers took note and began to run comic strip–style ads where characters discussed a product. Comic strips allowed advertisers to integrate dialogue, product information, and a sequential narrative into static media, such as magazines and newspapers. Comic books, introduced in 1934, also became a staple for younger readers. As the world slid toward a second world war, comic art had become a universally recognized form in American media.

Not everyone was happy about the pervasiveness of comics. As their popularity grew, so too did criticism of the medium, especially among educators and religious authorities. According to Amy Kiste Nyberg, author of Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code, educators felt comic books distracted students from higher quality material, taught them unrealistic behaviors, exposed them to art of inferior quality, and celebrated lewd, lascivious, and rule-breaking behavior. Comics were low culture, vulgar and cheap; their readers were dim and poorly educated. As one critic put it in 1908, the comic supplement appealed to people “who don’t care for fine shades of humor, because they can’t appreciate them.”

For other critics, comic strips were another example of how reading skills had been damaged and devalued by the fast pace of modern life. University of Wisconsin professor Harry Glicksman complained in 1923:

A 1930 study of the newspaper-reading habits of seventh-grade girls in Brooklyn revealed that 39 out of 40 read the comics, while only 3 read the news headlines. “In general,” an education researcher concluded, “newspaper reading was not as such might be considered educationally advantageous.” To many educators, comics were a degraded medium for fun and commerce, not learning.

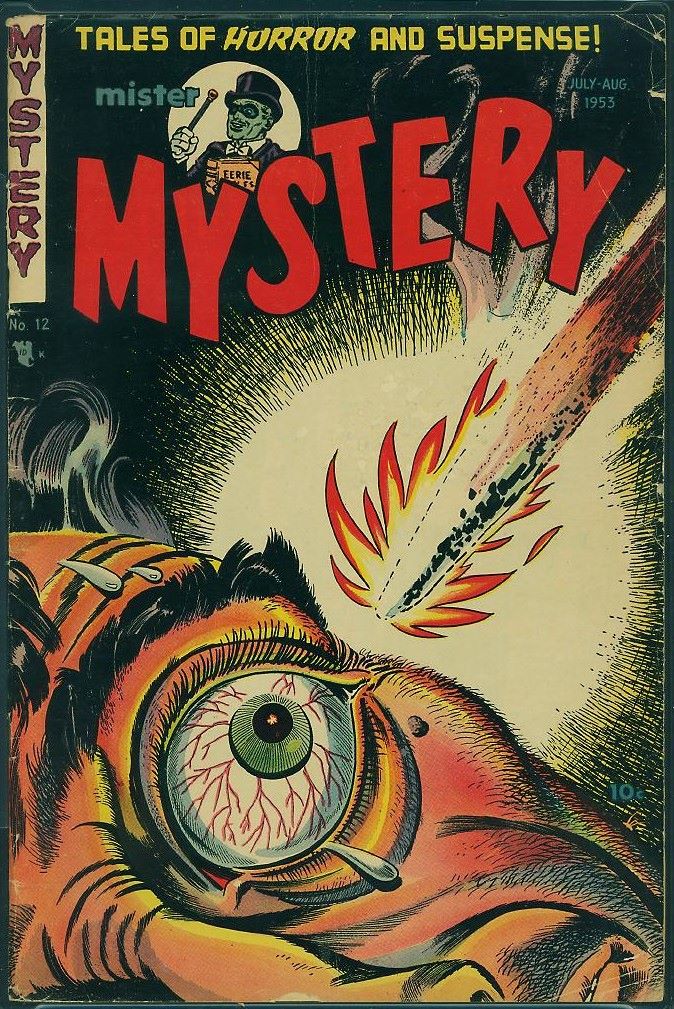

Comic books were even worse. The late 1930s saw an explosion of cheap comic magazines and the arrival of many of the superheroes who populate our movies today. But comic books printed in the 1930s and 1940s also featured a great deal of horror, explicit violence, and sexually suggestive content.

In 1940 writer and critic Sterling North published an essay that helped whip up public concern. After reading a selection of comic books, he concluded that “these lurid publications depend for their appeal upon mayhem, murder, torture and abduction—often with a child as the victim. Superman heroics, voluptuous females in scanty attire, blazing machine guns, hooded ‘justice’ and cheap political propaganda were to be found on almost every page.”

North seemed almost equally offended by the unrefined artwork and the cheapness of the paper as by the sex and violence. Like many others, he framed his critique in “think of the children” terms:

As the gyre of World War II widened and armed forces expanded, military commanders set about the task of training millions of draftees from across the social and educational spectrum. Training materials and military manuals evolved to meet these new demands. In the United States and Britain, comic art became an integral strategy for teaching the technical tasks essential to modern warfare.

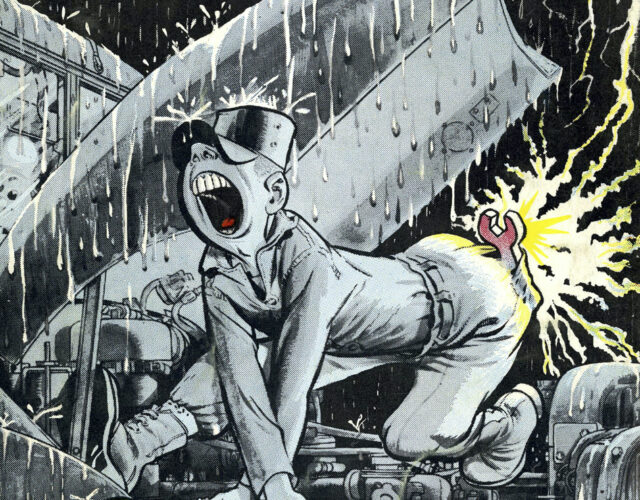

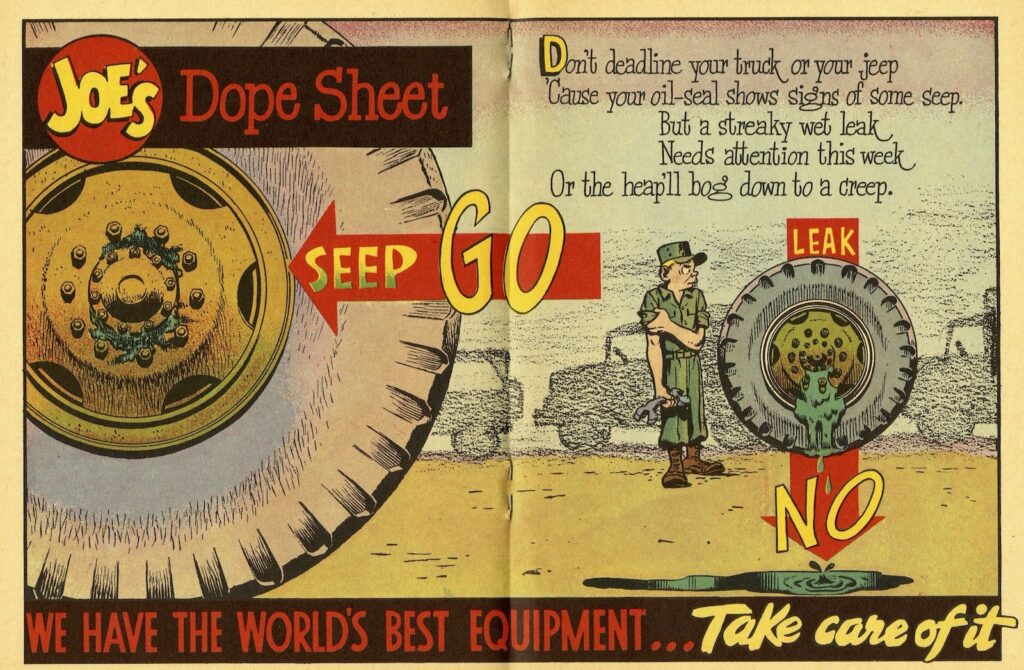

Comic book legend Will Eisner was among those who made comics central to army training. Eisner had created The Spirit—a comic book series full of voluptuous women and hooded justice—before being drafted into the U.S. Army Ordnance Department. In 1942 he became the artistic director for a minor publication, Army Motors, which promoted preventative maintenance of military vehicles. He created a lovable loser, Private Joe Dope, who always did things wrong, showing his readers what not to do. As the army’s ranks swelled, so did its need for training materials. Eisner became responsible for developing instructional comic strips for the army’s Technical Manual series.

After encountering a military unit largely composed of illiterate soldiers, Eisner realized training manuals needed to reach their readers at the most basic level—through simple and clear visuals. While photographs could offer exact illustrations of a machine and its parts, comic drawings could exaggerate important elements and annotate the actions needed to operate or repair such a machine. This integration of image and text, combined with humorous elements familiar to comic art, made essential lessons easy to absorb and remember. Comics were also cheap to print and easy for soldiers to carry.

Comics might be useful in reaching the poorly educated; could they also be used to communicate sophisticated scientific concepts, such as in physiology or meteorology?

As a young man, Eric Sloane painted the insignias on pilots’ planes at Roosevelt Field on Long Island, New York, and learned to fly from Wiley Post, the first person to fly around the world solo. He sold a painting of clouds to Amelia Earhart, and the sky became a subject the artist would return to throughout his life. He even informally studied meteorology at MIT under Sverre Petterssen, one of the foremost weather forecasters of the mid-20th century and a key member of the team that created the D-Day invasion forecast.

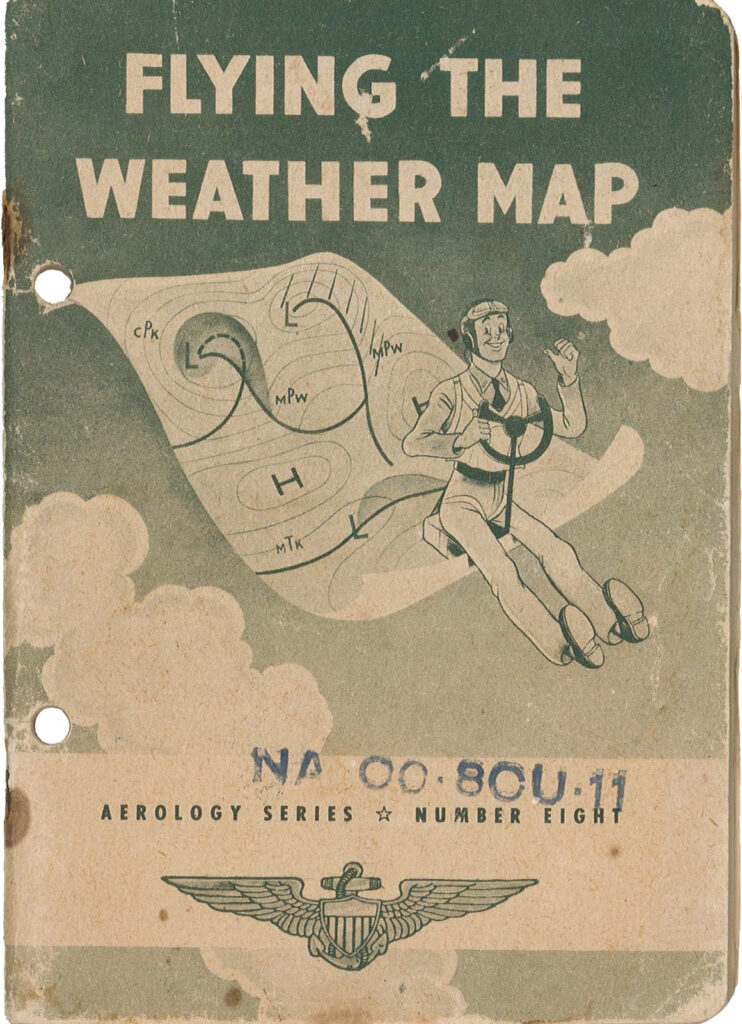

Sloane’s work for the military—comic book–style manuals such as Clouds, Air and Wind (1941) and Your Body in Flight (1943)—helped pilots remember the welter of information necessary to fly and fight effectively.

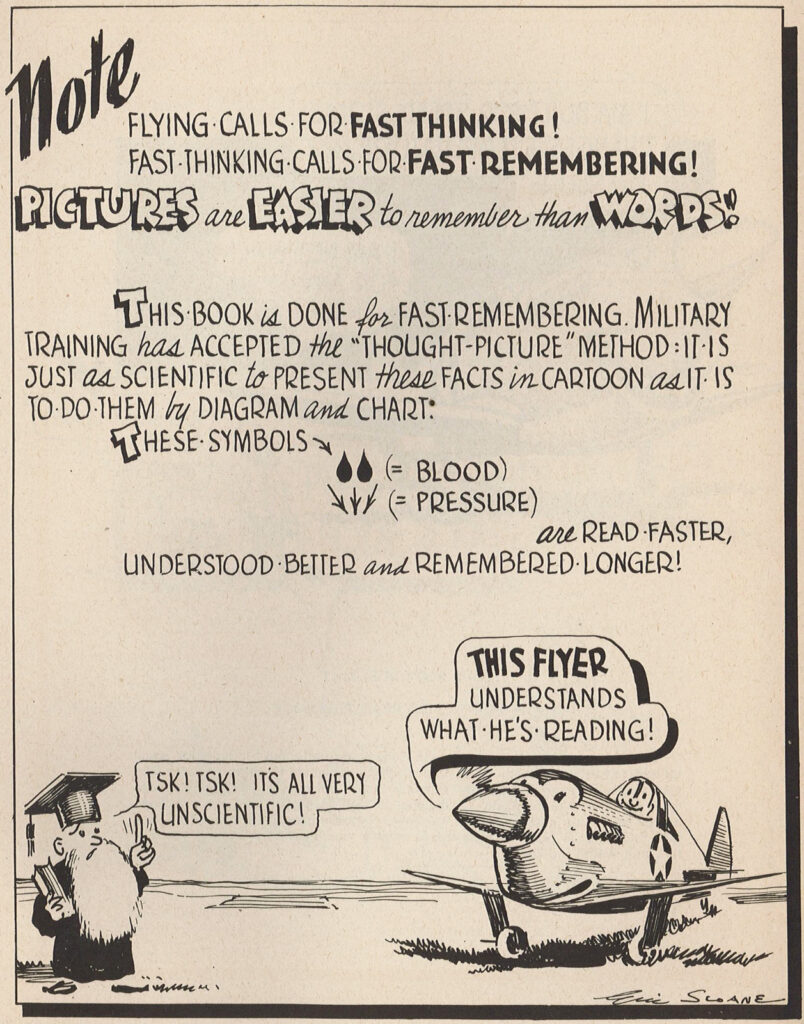

“Pictures are easier to remember than words!” Sloane writes in Your Body in Flight. “Military training has accepted the ‘Thought-Picture’ method: it is just as scientific to present these facts in cartoon as it is to do them by diagram and chart.”

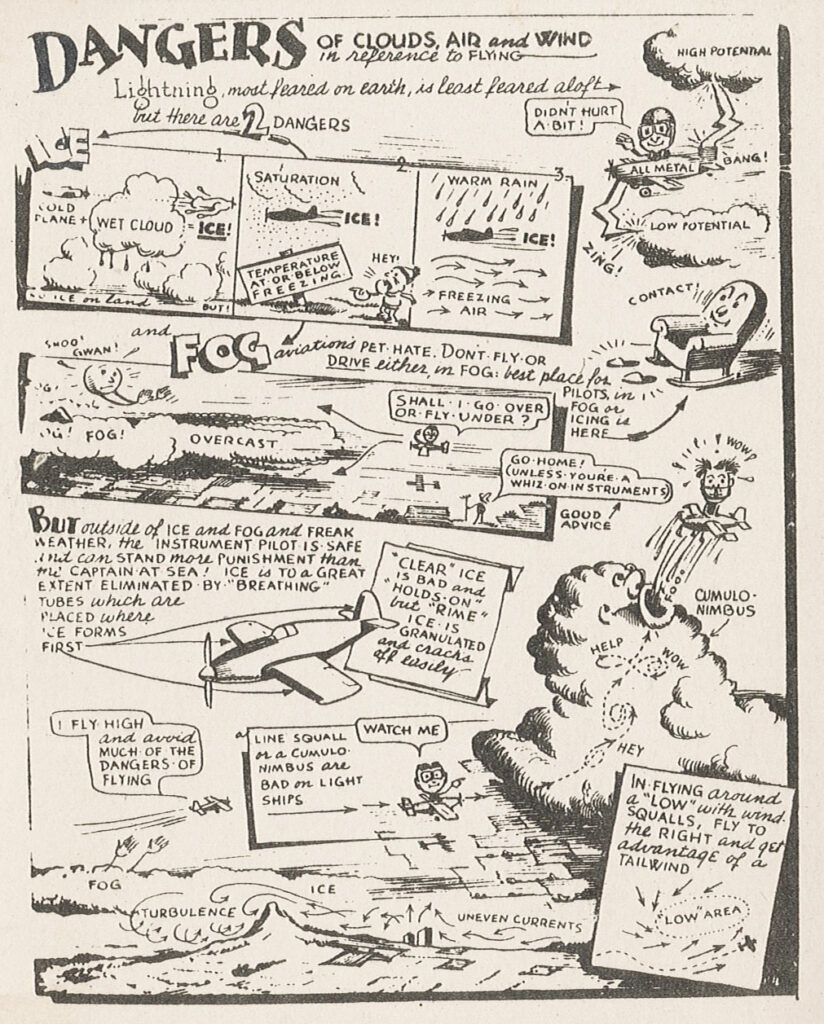

The power of this method is revealed in an illustration from Clouds, Air and Wind that lays out natural dangers pilots might confront. Sloane shows why pilots need not fear lightning but should worry about fog and ice. He describes the varieties of ice that threaten planes, how they form, and the mechanical devices used to combat them. He shows where dangerous turbulence can be found and how to avoid it. Finally, he throws in a tip for gaining an advantageous tailwind. All this is achieved through the conventions of comic art, including dialogue balloons, motion lines, a sequence of frames, expressive lettering to suggest sound, personification of inanimate objects, and visual cues for depicting emotion. In a single page, he conveys a wealth of flight safety information far more memorably than the column of prose set on the facing page.

Despite comics’ success in military training, Sloane betrays a defensiveness about his work in one scene from Your Body in Flight. “Tsk! Tsk!” chides a professor in his mortarboard, “It’s all very unscientific!” But a grinning fighter plane shoots back, “This flyer understands what he’s reading.”

Others in the military picked up and used these comic tools to relay dry, technical information. Maud Greenwood was one of about 100 Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) who received advanced training as weather forecasters during the war. WAVES forecasters and another 6,000 weather officers briefed pilots about the weather they were likely to encounter, a task crucial for pilot safety and for ensuring planes would arrive at the right target at the right time.

After completing a nine-month program at the University of Chicago, Greenwood was posted to the Naval Air Training Base at Corpus Christi, Texas, where she briefed student pilots on the conditions they would face during training hops. But Greenwood struggled to hold the attention of her recruits while explaining intricate synoptic maps layered with isobars and weather station observations. She started illustrating her forecasts with cartoons. As she remembered it, “The commander of the aerology office saw my drawings, liked them and put me to work painting weather pictures on the walls and special stands around the base. Next thing you know, I’m on my way to Washington, D.C. as a meteorologist/artist to help with aerological publications.”

After the war, comics changed in complicated ways.

Following the urging of Sterling North and other critics, parents, teachers, and politicians banded together in an effort to rein in comic books. In 1954 Senator Estes Kefauver chaired congressional hearings into comic books and their connections to juvenile delinquency. The leading comic book publishers responded to this pressure by agreeing to follow the Comics Code, a self-censorship policy very similar to the Motion Picture Production Code of the 1930s. This constrained how comics would depict sex, violence, and forms of social “deviance,” making the comic book a considerably more conservative medium then it had been in the 1930s and 1940s.

Some comic book publishers responded to public concern by pivoting from entertainment to education. One such figure was Max Gaines, a former school superintendent. Gaines ran All-American Comics, which had created Wonder Woman and Green Lantern, among other characters. Believing the superhero fad was ending, in 1945 he sold his stake to his partners and organized Educational Comics. Gaines aimed to publish a series of “frankly educational materials in comic form,” though his plans did not outlast his death, in 1947, at age 52.

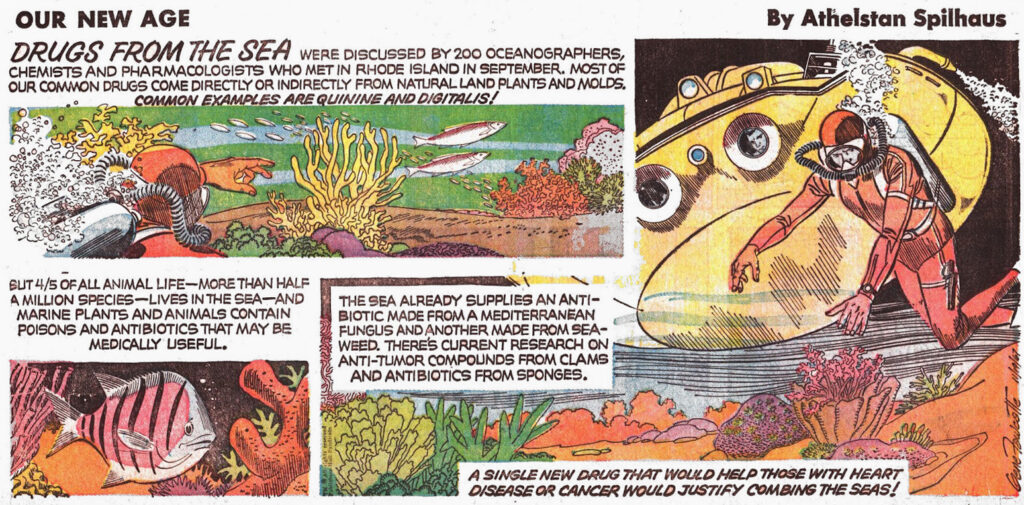

Some scientists also turned to comics as an educational medium. Athelstan Spilhaus had taught meteorology during World War II before parachuting into Nazi-occupied territory to establish a covert weather-reporting system. From 1958 until 1973, Spilhaus wrote Our New Age, an educational Sunday comic syndicated in more than 100 newspapers. Each strip explained a recent advance in science or technology, describing the implications for the daily life of Americans, such as in a 1967 strip that explained how satellite-mounted spectrometers might increase fishing harvests.

Spilhaus sometimes faced skepticism from his fellow scientists. But to the professors who questioned the value of writing comics, Spilhaus said, “Which of you has a class of five million every Sunday morning?” When Spilhaus met President John F. Kennedy in 1962, Kennedy told him, “the only science I ever learned was from your comic strip in the Boston Globe.”

The TV weather report may be where the comic art of World War II has had its most significant long-term influence. This style of reporting was largely invented by ex-military meteorologists who had been trained in the same wartime programs as Maud Greenwood.

One of the most influential early “weathercasters” was Louis Allen, who had served as a sea-and-swell forecaster during the invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. In 1948 Allen developed a weather report for WNBW (now WRC) in Washington, D.C. He first sketched a simplified weather map during the broadcast, narrating the weather situation as he drew. Turning to a new page on his easel, he presented the forecast by drawing a “woodle” (a portmanteau of weather doodle) that represented the next day’s conditions. He finished the report by drawing a lucky viewer’s name from a jar to receive that day’s cartoon. As one viewer wrote in a letter to WNBW, Allen’s maps and doodles “make a subject, otherwise technical, very easy to follow.”

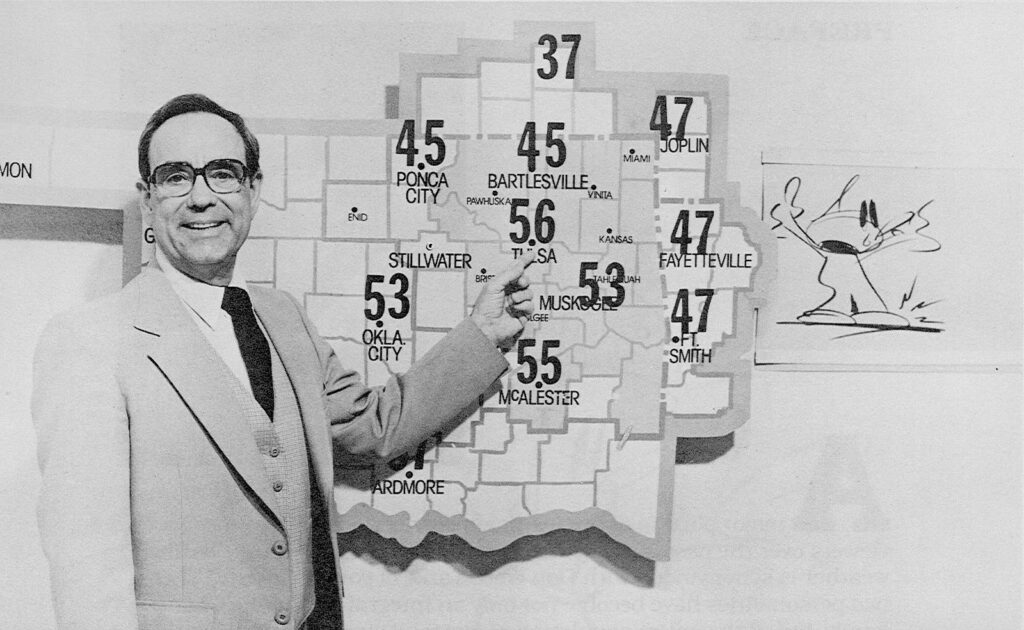

TV stations across the country noticed viewer interest in weather reports and the sponsorship opportunities that came with that interest. Allen’s program became a model for how to engage an audience while retaining a fairly sophisticated explanation of weather. Some TV station managers even made cartooning a job requirement. Meteorologist Don Woods got his first broadcasting job only after taking cartooning lessons. His signature drawings of a spritely swirl named Gusty made him a popular personality with Oklahoma TV viewers from 1954 until 1989.

While cartoons improved the public’s understanding of meteorology, the persistent association of comics with “low culture” has also devalued the work of weathercasters. During the 1950s and 1960s, station managers (and even a few weathercasters themselves) sometimes described the weather report as a “dull subject” in need of the “sugarcoating” provided by cartoons or clowning. In fact, repeated studies of TV weather reports across the decades have shown that viewers deeply value presenters who can engagingly deliver a bit of meteorological education mixed with the desired information about tomorrow’s weather.

Today comic art is as vibrant and popular as ever. Comic books remain widely read, and cartoons and comic book characters dominate summer blockbusters. Creators of graphic novels have succeeded in getting what Will Eisner called “sequential art” taken seriously as high culture. Yet that tone of defensiveness persists when educators talk about how they use comics to teach students. If it’s fun, it can’t be real learning. “Tsk! Tsk!” says Eric Sloane’s skeptical professor from somewhere inside our head, “It’s all very unscientific.”