At the tail end of World War II, Irma Materi left Seattle for Korea to join her husband, Joe, an army colonel. The couple and their new baby moved into a white stucco house with a red tile roof—and scores of nooks and crannies for insects to hide in. Fortunately, Materi had packed just the thing to address the problem: a grenade-shaped canister containing the new insecticide DDT, which she sprayed on high shelves, in dark corners, and under furniture and cabinets.

A few days later the Materis received a visit from the army’s DDT detail: a lieutenant and a dozen men wearing white jumpsuits with large spray packs strapped to their backs. As Materi scrambled to carry the family’s clothes, linens, utensils, and food to safety, the team doused the home with a solution of kerosene and DDT. Materi later wrote about the experience:

The army detail’s enthusiastic use of DDT is a familiar part of the pesticide’s postwar story. So too are the stock images from the late 1940s and 1950s that show American housewives drenching their kitchens with DDT and children playing in the chemical fog emitted by municipal spray trucks. Newspaper articles and advertisements called DDT “magic” and a “miracle”—which is likely why Materi took DDT along on her transpacific journey.

But articles and ads also cautioned that DDT was a substance to be handled with care—which is why there were limits to how much DDT Materi would tolerate in her home and why some Americans, such as Georgia farmer Dorothy Colson, wouldn’t tolerate DDT at all. Colson spent the late 1940s trying to launch a movement against DDT, convinced it was making Americans sick and killing off chicks and bees. To her it made no difference that the pesticide had—as the 1948 Nobel Prize committee put it—saved the “life and health of hundreds of thousands” from such insect-borne diseases as typhus, malaria, yellow fever, and plague. Where such diseases didn’t threaten people, Colson argued, DDT wasn’t worth the risk.

Materi’s anger at the overuse of DDT and Colson’s outright rejection of the pesticide don’t typically appear in the story of the now-infamous chemical. From history books to the recent news reports on Zika virus, accounts of DDT remind us that postwar Americans were so enamored with the pesticide’s potential to kill disease-carrying and crop-destroying pests that they quickly and enthusiastically embraced it. Nary a question about its toxicity or long-term risks was raised, we are led to believe, until Rachel Carson outlined them in her 1962 book, Silent Spring. DDT’s history is frequently invoked not only because the powerful pesticide was considered one of the most important technologies to emerge from the war but because we still struggle to control deadly and debilitating insect-borne diseases—Zika being the latest case in point.

We simplify the pesticide’s story because that stripped-down version of DDT’s history buttresses our understanding of the past. DDT’s powerful ability to control disease made the pesticide a hero of the war, and its development by American scientists still stands as proof that the United States earned its superpower status in large part through its scientific and technological prowess. The public’s acceptance of the chemical captures American postwar faith in scientific expertise. And its vilification by environmentalists serves as a powerful and lasting illustration of the baby boomer generation’s antiauthoritarian turn. Here, in short, is one chemical whose story illustrates some of the most profound social and cultural shifts in 20th-century U.S. history.

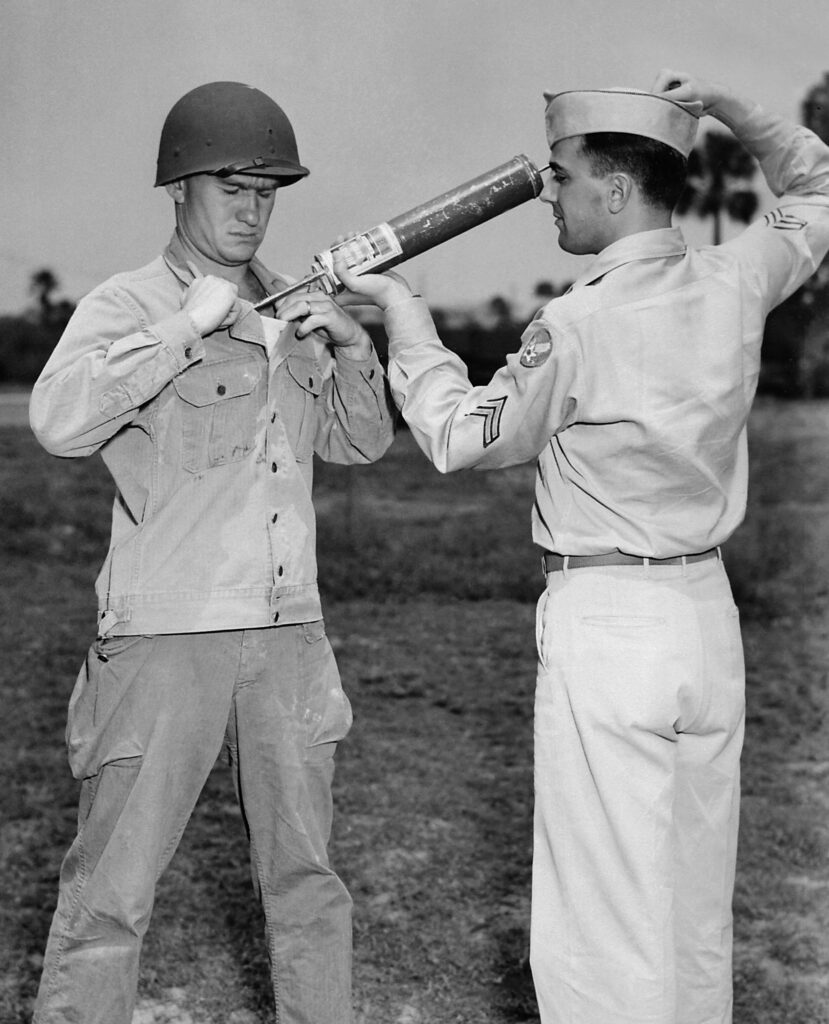

Soldier in an Italian home spraying a mixture of DDT and kerosene to control malaria, 1945.

But what happens if we tell DDT’s story differently, by leaving out the Nobel committee, for example, and instead tuning into what Materi, Colson, and like-minded Americans were saying during the pesticide’s heyday? This side of the story reveals a public more circumspect about DDT than many of the experts and authorities promoting its use. This version reveals a citizenry accustomed to thinking of pesticides as life-threatening poisons, worried about this new insecticide’s toxicity, and uncertain about how to interpret assurances of its safety. This story shows that many Americans needed to be convinced that DDT was a technology worth adapting to peacetime use. And this story calls into question the claim that the nation wholeheartedly accepted DDT. Government agencies (some more than others) did turn to it with increasing frequency, and so did our industrializing agricultural industry. The American public bought into DDT, too—but more unevenly than we’ve been led to believe.

The American public first heard about DDT in early 1944, when newspapers across the country reported that typhus, “the dreaded plague that has followed in the wake of every great war in history,” was no longer a threat to American troops and their allies thanks to the army’s new “louse-killing” powder. In an experiment in Naples, Italy, American soldiers dusted more than a million Italians with DDT, killing the body lice that spread typhus and saving the city from a devastating epidemic. It was a dramatic debut.

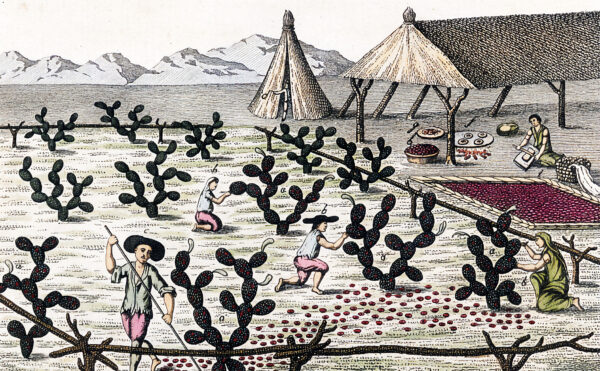

DDT quickly began to work its magic on the home front, as well. In the seasons that followed, newspapers reported that in test applications across the United States the pesticide was killing malaria-carrying mosquitoes throughout the South and preserving Arizona vineyards, West Virginia orchards, Oregon potato fields, Illinois cornfields, and Iowa dairies—and even a historic Massachusetts stagecoach with moth-infested upholstery. A peacetime vision for DDT bloomed: here was a wartime discovery that would prevent human disease and protect victory gardens, commercial crops, and livestock from infestations as it turned schools, restaurants, hotels, and homes into more comfortable, pest-free places for people and their pets.

DDT was a poison, but it was safe enough for war. Any person harmed by DDT would be an accepted casualty of combat.

In October 1945 National Geographic ran a feature on the “world of tomorrow,” in which transatlantic rockets would speed mail delivery, stores would sell frozen foods from exotic lands, clothes would be coated in waterproof plastic, and electronic “tubes” and “eyes” would do everything from stacking laundry to catching burglars. Health and medicine would be vastly improved, too, thanks to sterilizing lamps, penicillin, and, of course, DDT. “But scientists are treading with caution in their use of DDT, because it kills many beneficial insects as well,” the authors added. In an accompanying photo—an image that’s now iconic—a truck-mounted fog generator coated a New York beach in DDT as young children played nearby. The pesticide had halted a typhus epidemic in Naples, the caption read, but it “also has a drawback—it kills many beneficial and harmless insects, but it does not kill all insect pests.” Crops, flowers, and trees dependent on pollinators could die off, as could birds and fish.