When General Robert Bullard took command of the 1st Division of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) at Ansauville, France, on February 5, 1918, he told his soldiers not to wait for the enemy to fire first. “There are no orders which require us to wait for the enemy to fire on us before we fire on him,” he said. That very day two heavy batteries engaged German gun positions. “Gave them plenty of gas,” the gunners noted. In return the 2nd Battalion Battery C 7th Field Artillery was shelled and gassed by its German foes. But Bullard’s orders had only amplified U.S. artillery activity; they had begun firing cyanogen chloride and phosgene shells on February 1, the day before the first recorded German chemical attack on American forces.

American readiness to swing first in this tit-for-tat exchange of chemical shells underscores the AEF’s participation in the “Chemists’ War.” By the time the United States entered the war in December 1917, the use of chemical weapons by both sides was widespread. The United States swiftly developed its own infrastructure for the development and production of chemical weapons. The 1,900 scientists and technicians mobilized by July 1918 composed the largest government research program to date. By the end of the war 10 facilities in the United States employing more than 10,000 men and women were producing over 140 tons of gas per day, more than Germany, Great Britain, and France combined.

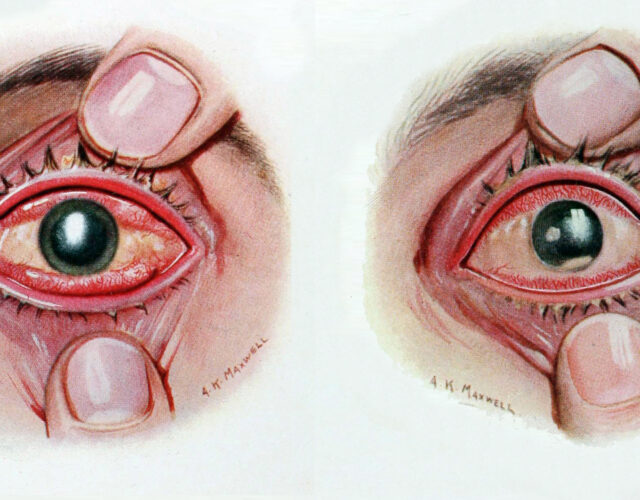

An artifact in the rare-book collection of the Othmer Library bears sad witness to the human dimension of chemical warfare. In 1918 the American Red Cross published An Atlas of Gas Poisoning for the AEF. Thin and gruesomely illustrated, it was meant to help inexperienced officers recognize the characteristic effects of exposure to phosgene and mustard gas (dichloroethyl sulfide), the two predominant battle gases. Its 13 colored plates are drawn from life and depict burns, blisters, and pallor on faces, torsos, buttocks, and genitals. Sparely written case histories accompany the illustrations and note the progression of the injuries and how long the victims lived or whether they recovered.

The victims of chemical warfare were not restricted to troops engaging the enemy. In 1918 there were 925 casualties and 4 fatalities related to gas production at Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland. Of course not all industrial accidents occur during wartime, and such chemicals as phosgene have industrial uses to this day. It is a fitting tribute therefore that an anonymous donor adopted CHF’s copy of An Atlas of Gas Poisoning and dedicated it “In memory of chemical workers who died by accidental exposure to phosgene.”