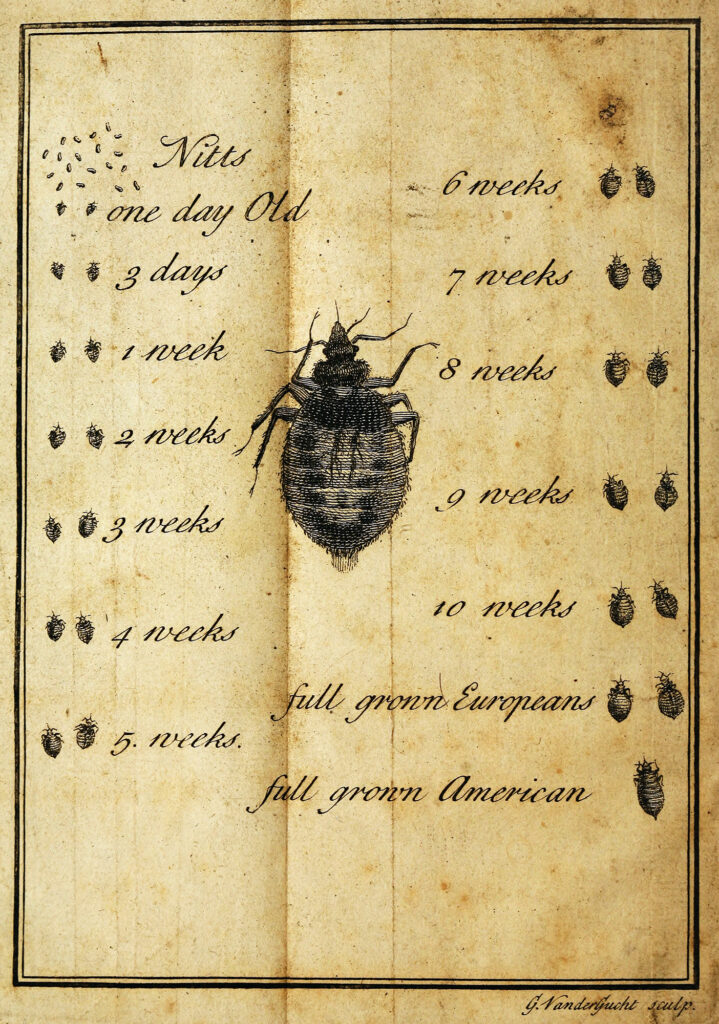

Naturalists William Kirby and William Spence both agreed bedbugs had come to England via international trade: “Commerce, with many good things,” they wrote in the 1818 edition of their Introduction to Entomology, “has also introduced amongst us many great evils, of which noxious insects form no small part.” Kirby and Spence concur with all who described bedbugs from the 17th century on—their subject is nauseating.

They are among those 18th- and 19th-century naturalists and others who linked a lack of cleanliness with the prevalence of bedbugs. Indifferent and poor Londoners caused their own infestations, according to Kirby and Spence: “however horrible bugs may have been in the estimation of some, or nauseating in that of others, many of the good people of London seem to regard them with the greatest apathy, and take very little pains to get rid of them.” The 1863 edition of Miss Leslie’s Lady’s House-Book warned that, when moving into “an old house which has had various occupants, these disgusting and intolerable insects frequently make their appearance.”

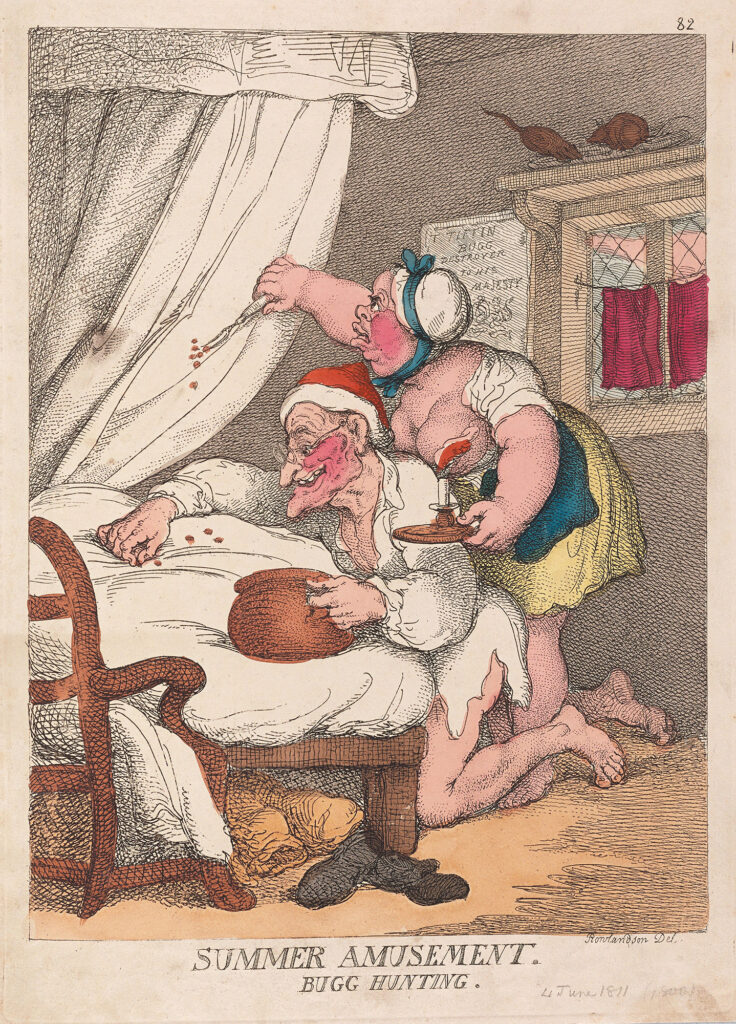

Summer Amusement, Bugg Hunting, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1811.

Kirby and Spence were among the many cleric-naturalists who viewed nature as revealing God’s design, but this view of a divine harmony in nature did not necessarily include bedbugs. They took their cues on the matter from Linnaeus, the great Swedish naturalist, who described the bedbug as a “troublesome and nauseous inhabitant of most houses in large Cities: crawling about in the night-time to suck the blood of such as are asleep, and hiding itself by day in the most retired holes and crevices.”

An 1819 dictionary reprinted this description verbatim and further depicted the bedbug as “a perfect glutton, never ceasing . . . till it is completely gorged and can hold no more.” Judgment on the bedbug—and on those whose homes harbored it—was dispensed by many, including the Harvard entomologist and botanist Thaddeus William Harris, who maintained that the insect inherited its name from the “bugbear” of earlier times, which were “objects of terror and disgust by night.”

Modern science has revealed the bedbug in all its goriness. In one feeding, bedbugs can suck up enough blood to last them several days. If their host vanishes, the bedbug can hibernate without food for more than a year. It takes a dryer running on the highest possible heat setting for 30 minutes—or a home heated to a temperature of 118°F for 70 minutes—to definitively kill bedbugs. But, as the University of Minnesota Extension Service explains, bedbugs are “great hitchhikers,” and such efforts don’t prevent them from reinfesting a location at a later date.

The hunt for an effective eradication method goes back to at least the 18th century. John Southall, a bedbug aficionado and Britain’s first professional exterminator, recognized that bedbugs could survive a cold winter and reappear with warm weather. For two shillings Southall would sell the beleaguered a secret elixir, the recipe for which he claimed to have wheedled from a former slave. French encyclopedist Noel Chomel offered other solutions. He recommended arsenic, euphorbium, and bay leaves, but the best way to get rid of bedbugs, in his opinion, was to use a cat.

Such remedies faded slowly from folk memory. In the 19th century, scientists, entrepreneurs, entomologists, and home economists continued the war against bedbugs with old and new tools. Most recommended mercury, turpentine, gasoline, and arsenic, weapons also used by bug killers in the 18th century. Leslie recommended these substances but also added powdered camphor and sweet spirit of nitre (the latter now called ethyl nitrite and banned by the FDA for over-the-counter sales). A growing reliance on science crept into the bedbug trade. As an exterminator named Tiffin declared about his method, “I may call it a scientific treating of the bugs rather than wholesale murder.” One inventor even pitched a steam engine, the Bedbug Exterminator, as a way to fight off the “remorseless cannibals.”

By the 20th century, pyrethrum, hydrogen cyanide, and other chemicals were added to the arsenal. But most of these treatments killed only mature bedbugs, leaving their offspring to flourish another day. Then DDT arrived in the middle of World War II. Fred Bishopp, the head of the U.S. Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine, while cautioning against indiscriminate use, described DDT as a “magic insect killer” that wipes out flies, lice, and, of course, bedbugs. In fact, the annihilation of “these disgusting pests is almost unbelievable.” Bedbugs had inhabited almost one-third of London homes before World War II and happily roomed with patrons of railway inns, barracks, movie theaters, brothels, and other common meeting places. Now they were vanquished without the bother of squishing them.

In 1976 pioneering entomologist J. R. Busvine warned that bedbugs had grown increasingly resistant to pesticides and were poised for a comeback. This resurgence was bolstered by the banning of DDT in most developed countries. By 2008 bedbugs had again become common companions in households and businesses. Entomologists suddenly found themselves sought after; exterminators were viewed almost as saviors.

Rather than roasting cats, modern bug killers hunt out bedbugs with trained dogs (though some trainers have been accused of falsely identifying bedbug infestations). The smart device industry is also on the bedbug trail. The Automated Insect Monitoring system detects crawling bugs, identifies them by the sound they emit, and then sends an alert to subscribers.

Still, scientists face considerable problems in devising new strategies for controlling and ending the onslaught. Until recently, much of our knowledge of bedbugs was based on old stock that was far less pesticide-resistant than the breeds we now encounter in our bedrooms. It takes 10,000 nanograms of the insecticide acetamiprid to kill 21st-century bedbugs as opposed to the 0.3 nanograms for earlier bugs.

But research continues. Scientists have sequenced the bedbug genome and now understand how the creatures outgrew their vulnerability to pyrethroids, synthetic pesticides similar to a chemical found in the chrysanthemum plant, as well as the most common insecticides. Other researchers are finding new substitutes for these insecticides in the natural world, including neem oil and various essential oils derived from oregano, basil, thyme, cloves, and lemongrass. Many of these are already for sale and have demonstrated various degrees of effectiveness. A more popular and successful class of pesticides are the neonicotinoids, similar in composition to nicotine—though bedbugs don’t have to smoke them to suffer their deleterious effects.

Some researchers have suggested that pheromones may be the key to a life free of the bloodsuckers. Bedbugs reproduce by a method called “traumatic insemination,” in which the male burrows a hole and injects its sperm into the abdomen of the female (which has no genitalia of its own). The males don’t discriminate in their sexual advances—they will attack other males and immature nymphs, killing them. So when these males advance, potential targets pump out alarm pheromones that both repel the males and send their compatriots scurrying. Scientists may be able to use these chemical signals to drive these maddened bedbugs onto traps infused with desiccant dusts, drying them to death.

There may be a downside to dousing bedbugs with manufactured pheromones. Entomologists have suggested the blood sucked up by bedbugs could be used to catch criminals using DNA analysis. (And let’s not forget, they do provide employment opportunities for exterminators and dogs.)

On a less practical but perhaps more profound level, bedbugs may offer a way to better understand evolution. “For something that is so hated by so many people, it might just be a perfect model organism for evolutionary questions,” University of Tulsa biologist Warren Booth told the New York Times in 2015. Using DNA analysis, Booth and his fellow researchers discovered that the bedbugs living on humans may be mutating into a new species as they become resistant to pesticides.

If bedbugs don’t carry disease and their bites are relatively harmless, why do people hate them so much? Partly it’s because they attack when we are asleep and at our most vulnerable. They also challenge our sense of entitlement and independence. Bedbugs surged on the rising wave of globalization and pre-COVID international travel. They tag along in our luggage and backpacks, crossing borders with such ease as might make anti-immigration folks crazy.

Indeed, a guest who stayed in a luxury suite at the Trump National Doral Miami in March 2016 sued the resort for bedbug-inflicted injuries. “Trust me when I tell you it is horrible to wake up in the morning and understand that bugs were crawling all over you all night,” the injured party declared. That case was settled for an undisclosed amount before the 2016 election. The accusations against the Miami hotel resurfaced in newspapers after President Trump suggested it as the meeting place for a G7 conference. The president responded by venting on Twitter: “No bedbugs at Doral. The Radical Left Democrats . . . spread that false and nasty rumor.”

Bedbugs mock human superiority. Above all others, the creatures rebuke modern pretenses. People take for granted their power to sleep and travel where they want, to mold nature and the environment to their liking. Not so, says this tiny and cunning insect: You may try to use science to control and kill me, but I will outwit you. Drive me away and I’ll come back and occupy the home of the neighbor next door to boot.

Such vulnerability makes us paranoid. In a post-9/11 zeitgeist ever sensitive to symbols of a world out of control, the bedbug is the most horrifying of insects. But perhaps another pervasive threat—the coronavirus pandemic—can impede bedbug hysteria. As the New York Times columnist Jane Brody wrote, “Given the drastic pandemic-induced reductions in travel . . . the chances of being bitten by or bringing home these uninvited guests have been greatly curtailed.”

That may be true, but we can be sure that once COVID-19 is fully defeated, the bedbug will resume its merciless march across our pillowcases and skin.