In 1785 William Herschel was one of the most famous people on Earth, a self-taught astronomer and the first person in well over 2,000 years to add a new planet to the cosmos. Acclaim came quickly, and it won Herschel the backing of the curious and eccentric King George III, who loved to peer into Herschel’s exquisite, homemade observing instruments.

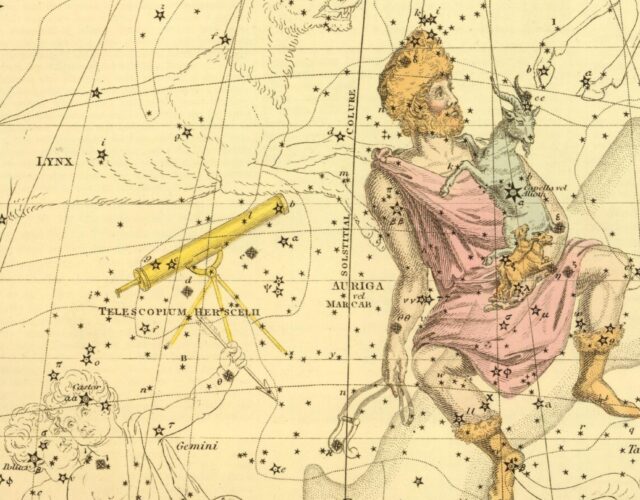

Herschel first noticed Uranus in the reflection of a 6-inch mirror housed inside a 7-foot-long reflecting telescope he made himself; however, he identified the curious object as a planet only after tracking it with a telescope nearly three times that size. Herschel went on to use this 20-foot telescope to describe distant clouds of light—star clusters and nebulae. If such an instrument could locate faraway galaxies, what secrets could an even larger telescope uncover?

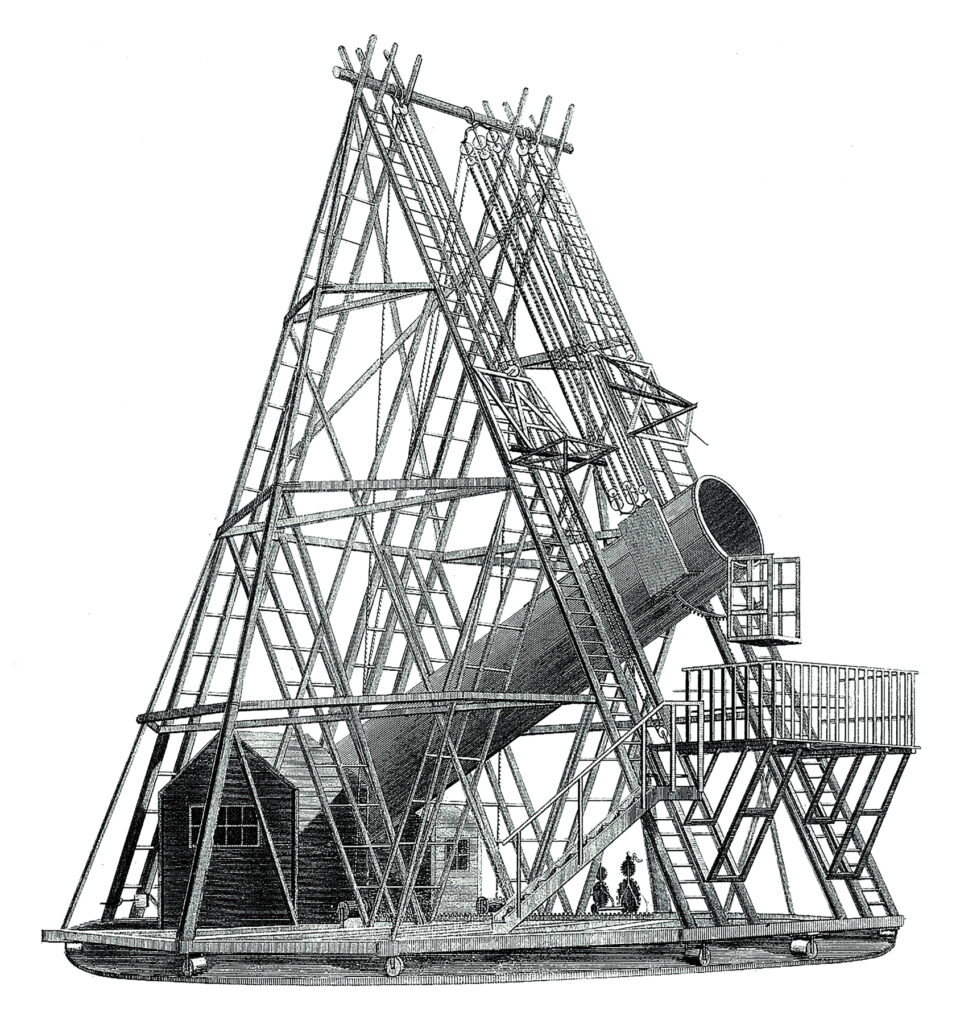

In 1785 Herschel began constructing an unprecedented 40-foot reflecting telescope to search out those secrets. The project would take years to complete, cost thousands of guineas, and test the limits of Herschel’s royal patronage. Once finished, though, the telescope was a sensation. Nobles and commoners alike made their way to the tiny village of Slough to see the colossal structure. Artists immortalized the telescope, depicting a massive cylinder pointed at the heavens and held aloft by a lattice of wooden beams. These illustrations were reprinted in books and pamphlets distributed around the world, giving people a glimpse at the largest scientific instrument ever built. Just as the French Revolution and ratification of the U.S. Constitution demonstrated an evolution of government and politics, so too did Herschel’s telescope provide evidence of humanity’s progress in science. In a letter to Herschel, German astronomer Johann Schröter gushed that the 40-foot telescope “shows how far human perseverance and zeal for the sublimest science can attain.”

But for all its acclaim the telescope as Herschel intended it was a failure. It did not see any farther or clearer than the telescopes that came before, and in the end the symbolism of the telescope was more remarkable than its gaze into space. How did Herschel’s telescope become one of the most celebrated disappointments in history?

Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel first came to England in 1757 not as a stargazer but as a sickly 19-year-old German deserter fleeing the Seven Years’ War.

Herschel was brought up in a family of army- band musicians, and that background provided his living during his early years in England. He gave lessons on many instruments, including the violin and the oboe. Herschel performed as a soloist, composed music (including 24 symphonies in his lifetime), and in 1766 was installed as the organist of a wealthy church in Bath.

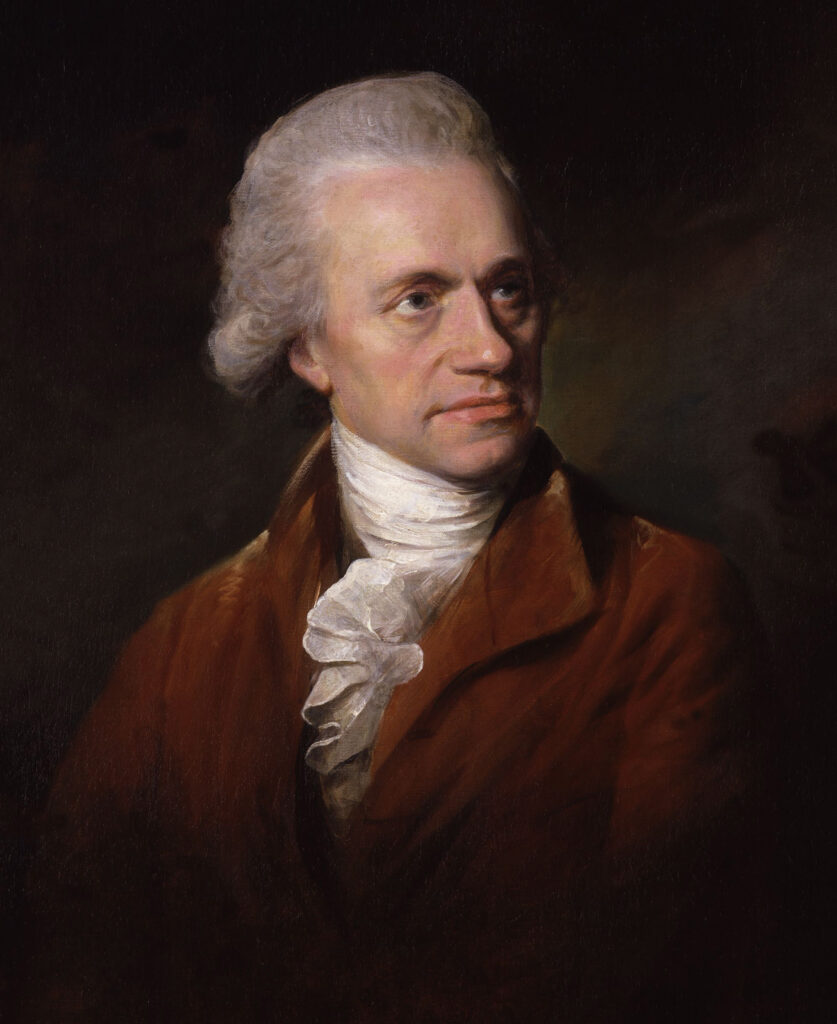

Portrait of astronomer William Herschel (1738–1822) by Lemuel Francis Abbott, 1785.

As Herschel circulated in English society, he began to encounter amateur astronomers who piqued his interest in the heavens. He studied the work of the Scottish astronomer James Ferguson and taught himself to build his own telescopes, which Herschel used to track the movement of moons and comets in the night sky.

Once Herschel was on solid financial footing, he reached out to his sister Caroline, who would be his constant collaborator in the years to come. In The Age of Wonder, Richard Holmes writes about Caroline’s childhood illnesses, including a smallpox infection that left her badly scarred and a typhus infection that stunted her growth. Her mother and older siblings deemed her too poor and unattractive to marry. Instead, she was expected to spend her life as the family’s unpaid servant, washing laundry, cooking meals, and fearing her mother’s retribution if she did not obey. During her bouts of illness she was left to fend for herself and on at least one occasion was forced to crawl down the stairs from her bedroom to eat because no one in her family would help her. Herschel offered his sister an escape from this drudgery: come to England to work as his assistant and have a more independent life. She accepted.

After an arduous journey, including a storm that knocked down the mast of the ship she was on, 22-year-old Caroline arrived in England in 1772 and moved in with Herschel. To her dismay Caroline was asked to perform the household chores, but she was repaid with an intensive curriculum administered by her brother that included lessons in English, music, math, astronomy, and singing. Within a few years she was fluent in English and was earning steady money as a singer.

At night Caroline learned to read the stars. Together brother and sister took detailed notes of the night sky and built telescopes using Isaac Newton’s designs from the 1660s. Most telescopes at the time, such as sailors’ spyglasses, used a convex glass lens that refracted light through a tube. One problem with this design was something called chromatic aberration, a distortion of the image caused by light being split into its component wavelengths by the lens, not unlike a prism. The separated colors resulted in a blurred image.

By the time Herschel was building telescopes, an English optician named John Dollond had mostly fixed the problem by combining two separate lenses that together corrected for the distorted light. But Herschel wanted to peer deeper into space than even the improved refractors of the day could reach. Reflector telescopes, like the ones built by Newton, used a single concave mirror that could collect more light than the smaller-aperture refractor lenses and so better capture far distant (and thus weaker) light sources. The light gathered by the concave mirror was reflected onto a flat mirror at the other end of the telescope, allowing Herschel to see farther than any one before him.

Newton only ever built small reflector telescopes—his first primary mirror was just 1.3 inches in diameter—because large, symmetrical mirrors were difficult to grind and polish. The tiniest flaw in a mirror led to blurriness that rendered the telescope unusable. (One advantage refractor telescopes continued to have over reflectors was that a lens was more forgiving than a mirror, thus refractors’ popularity.) Even in Herschel’s era no one was making telescope mirrors much bigger than 3 inches in diameter, and Herschel estimated he would need something at least twice that size to make deep-space observations. Herschel decided if no one could sell him the mirror he wanted, he would make it himself.

He sought out a man in Bath who made telescope mirrors as a hobby. After the man taught Herschel the basics of the craft, he bought the man’s tools and materials, including a metal disk composed of copper and tin; with Caroline’s help he ground and polished it into a 6-inch mirror. He then inserted the mirror into a 5-foot-long tube. Holmes writes that on the first night of observation with the new telescope “it was immediately apparent that Herschel had created an instrument of unparalleled light-gathering power and clarity.” Thanks to the high resolution, Herschel soon discovered that certain stars that appeared to be extremely bright, such as the North Star, were actually two stars with their light combined. He became obsessed with astronomy. Beginning with the construction of that first telescope, Herschel transformed their home from a music studio into a workshop full of hazards, all in pursuit of bigger and better mirrors. Caroline grieved for what became of their once-beautiful drawing rooms and bedrooms, now cluttered with “turning patterns, grinding glasses, and turning eye-pieces,” not to mention a basement furnace that was constantly threatening to explode. According to his sister, Herschel slept only when the clouds made it impossible to see the stars.

One night in 1779 Herschel was standing in the street near his house, examining mountains on the Moon with a new 7-foot reflector telescope he had built. A well-connected doctor named William Watson happened to pass by, and Herschel allowed him to look through the telescope. After speaking to Herschel about his observations, Watson realized this musician was doing more important astronomical work than anyone he knew at the Bath Philosophical Society. Watson encouraged Herschel to submit his findings to the society, and the doctor eventually sent the best research to his friends at the Royal Society in London.

In the years that followed, Herschel made a series of monumental observations. Over the course of a few nights in 1781, while studying a group of stars, he found something bigger (and therefore closer) than the points of light of the stars. Herschel initially thought it was a comet, but he soon suspected he had discovered a new planet, the seventh, and the first to be found since the ancient Babylonians recorded the movements of the other five (besides Earth) with their naked eyes. Once confirmed, the news stunned the world, and Herschel became a household name. In a canny move for royal patronage the ambitious astronomer named the planet Georgium Sidus (the Georgian star), though by 1850 it had been renamed Uranus.

Around the same time, Herschel was pursuing an even more eccentric proposal: evidence for life on the Moon. He claimed his new telescopes revealed vast forests, rich soil, and cities in craters designed to collect energy from the Sun. But Herschel could not find concrete proof and so never published his theory of an inhabited Moon. (In later publications, however, he repeatedly made reference to the idea that living beings resided on the Sun and every other planet. Why else, Herschel supposed, would God hang the sky with these celestial bodies? Although few astronomers went as far as Herschel, many shared his religion-based hunch that God wouldn’t create planets without populating them.)

Herschel became friendly with many of Watson’s connections at the Royal Society, and eventually the society’s president, Joseph Banks, a naturalist who had sailed with Captain Cook, became Herschel’s most vocal advocate. Banks was eager to connect Herschel with King George, who was known to have his own fascination with stars. In 1782, after learning about Herschel’s discoveries and exceptional instruments, the king offered Herschel a paid position as his personal astronomer. (The job description included entertaining the king whenever he wanted a look through Herschel’s telescopes.) William asked Caroline to give up her singing career and the high society of Bath and move with him to Datchet, just outside London, where he could practice astronomy full time. Grudgingly, she agreed and threw herself into the work of an astronomer’s assistant.

For years the Herschels collaborated to change the accepted understanding of the cosmos. They accomplished this through close observation and the creation of larger telescopes, including a 20-foot instrument with an 18-inch mirror finished in 1783. Through the heat of summer and cold of winter, Caroline sat at a desk, squinting over a half-covered candle to record her brother’s observations and confirm measurements and angles. The siblings rarely took a holiday or a night off from analyzing the sky inch by inch or, when clouds prevailed, grinding and polishing new mirrors. Caroline also began observing the sky on her own; her discovery of a new comet in 1786 made her a minor celebrity, and William convinced the king to give Caroline a salary of her own.

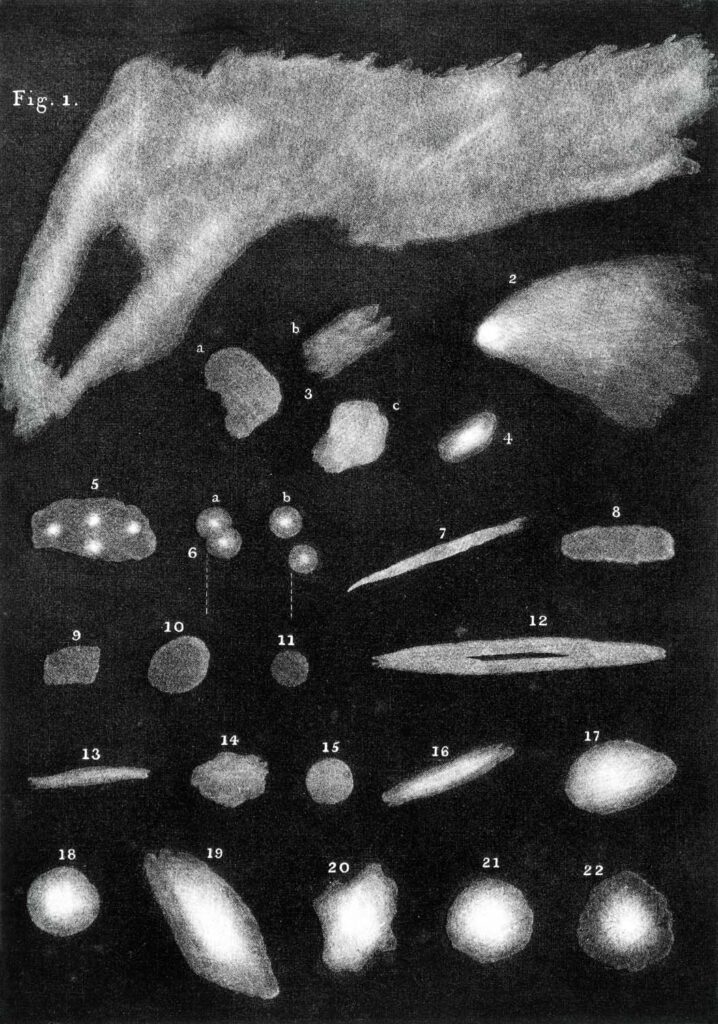

In addition to studying comets Caroline identified a handful of new nebulae, which were understood to be clouds of gas or star clusters too far away to see clearly. Inspired by Caroline’s discoveries, Herschel began studying nebulae more closely, which led to a paper challenging the prevalent conception of the universe.

Nebulae drawn by Herschel and published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1811. Herschel believed these nebulae might represent different stages of the life and death of stars.

Most astronomers at the time saw the heavens as a static dome embedded with stars, rotating around the solar system. Herschel, instead, suggested the universe was a vast, three-dimensional space where stars existed at varying distances. He also believed Earth’s solar system was not necessarily at the center of that universe and that nebulae were evidence the universe was constantly changing. He speculated that different types of nebulae were at different stages of life; some were partially collapsed clouds of gas that used to be stars, whereas others re-formed into different kinds of celestial objects. Because the Milky Way appeared to share many of the same characteristics as nebulae, his logic went, our galaxy was likely formed from a nebula too, and therefore one day it would collapse again and turn into something else. Essentially, Herschel was predicting the end of the universe.

Herschel was confident his theories about the shape and nature of the universe had merit, but he knew he would never be able to confirm them with the telescopes he had available. In 1785 he asked King George for funding to construct a new 40-foot telescope, which would be the largest and most expensive scientific instrument ever made. Thanks in part to an endorsement from Banks, Herschel received a grant to begin building later that year.

To prepare for the telescope, Herschel first insisted on moving to a larger estate in Slough, about 20 miles west of London. Herschel commissioned the casting of a 40-foot iron tube and the slab of speculum (an alloy of copper and tin) that would be polished into a mirror nearly 4 feet in diameter. He then oversaw construction of a gigantic rotating platform that would be used to reposition the telescope. Not surprisingly, the 5-year project went over budget. The king gave Herschel more money but not enough to complete the work.

As the end of the decade neared, the telescope was still not finished. Caroline recorded detailed descriptions of the hectic life on Herschel’s estate:

King George brought the archbishop of Canterbury for a tour during construction. Herschel walked them through the enormous metal tube before it was raised into place. Caroline later recalled in a letter how the king offered to help the archbishop inside. “Come, my Lord Bishop,” he called. “I will show you the way to Heaven!”

Once the main tube was locked into place and surrounded by a permanent scaffolding and viewing platform, Herschel spent the next several months perfecting the mirror’s focus. There was only one way to check the progress: hoist the half-ton mirror into the telescope and try to make observations with it. When Herschel determined where the mirror needed adjustments, his workmen would take it down, polish it, and then bring it back up. Unlike refractor telescopes, where the viewer would peep through the narrow end close to the ground, large reflector telescopes necessitated looking at the mirror itself. Herschel would make his observations while leaning over the lip of the suspended tube, looking down into the maw of his telescope.

An illustration of Herschel’s 40-foot reflecting telescope from Charles Hutton’s A Philosophical and Mathematical Dictionary, 1815. At the time it was completed in 1789, the telescope was one of the largest and most expensive scientific instruments ever built.

In 1789 Herschel finally declared the telescope finished; the mirror was as symmetrical as it was going to get. But he was unhappy with his creation’s performance.

As might be expected, moving the telescope to see different areas of the sky was time consuming and difficult. Gone were the days when the siblings could work by themselves: the 40-foot machine’s track required multiple people to turn it.

The 4-foot mirror alone weighed 1,000 pounds but was only 1- to 2-inches thick; it deformed under its own weight, forcing Herschel to commission a second, thicker mirror. This time Herschel used a harder alloy that included more copper. The new alloy was less likely to bend, but it caused the mirror to tarnish faster than the original in humid conditions. Throughout the telescope’s life Herschel constantly swapped out the two mirrors for reshaping or polishing.

Even when everything was working perfectly, the 40-foot telescope didn’t help Herschel confirm his theories about a changing universe where stars were born and died. Distant nebulae still appeared to him as undefined blobs, although that wasn’t necessarily the telescope’s fault; it’s unlikely that any mirror, no matter how large and perfect, could clearly capture the image of a nebula through Earth’s atmosphere. (It took the Hubble Space Telescope—launched in 1990 with its own mirror problems—to confirm that many of Herschel’s nebulae were actually distant galaxies.) One of the few discoveries Herschel made with the 40-foot instrument was identifying two new moons of Saturn, but he later admitted he could have made the same discoveries with his smaller telescopes.

Although Herschel’s historic telescope ultimately added very little to our astronomical understanding, scientists, writers, and the general public were enamored with it. In retrospect it is clear people were as impressed with the sight of the massive telescope itself as they were concerned with what the telescope could see.

According to Kathleen Lundeen, professor of English at Western Washington University, the telescope gave people a physical place and a recognizable symbol to represent the advance of science. Drawings of the massive contraption were printed in popular magazines, where it was described as a wonder of the modern world. The telescope was referenced in poetry, including in the writings of Erasmus Darwin and William Blake. In the 1804 epic poem Milton, Blake writes,

And every Space that a Man views around his dwelling-place:

Standing on his own roof, or in his garden on a mount

Of twenty-five cubits in height, such space is his Universe.

For Lundeen these lines allude to Herschel’s grandiose viewing platform atop his telescope; she points out that the 25-cubit mount matches the length of the 40-foot tube.

King George, far from disappointed by the lack of astronomical discoveries, was pleased the telescope drew tourists and foreign dignitaries, especially those from France, a frequent enemy that recently had outshone England in many fields of science, including astronomy. Finally, the king had a scientific instrument impressive enough to entice even arrogant French scientists to cross the Channel.

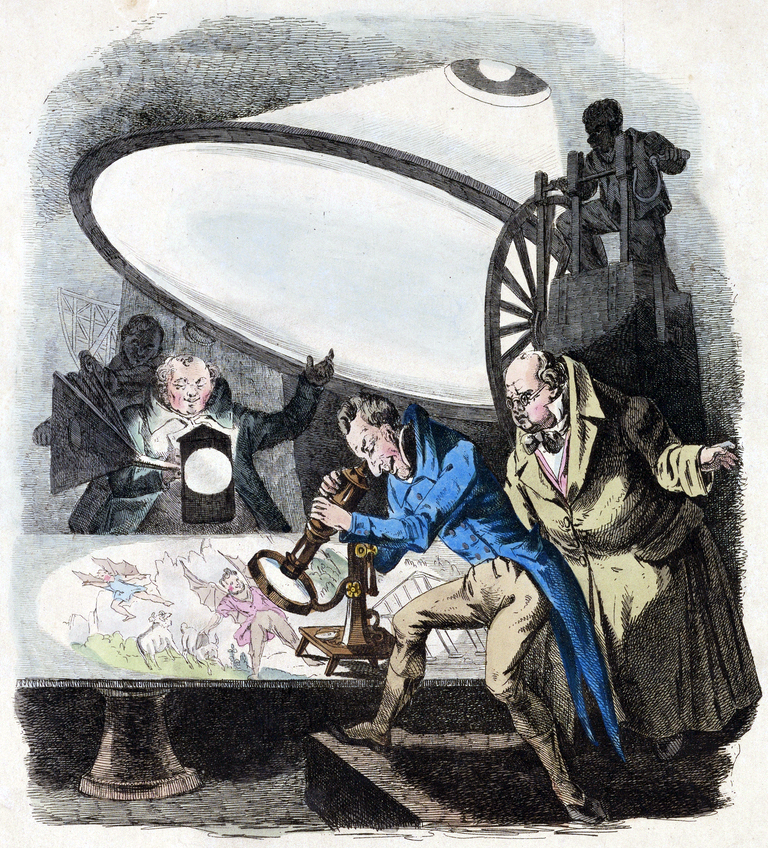

One of Herschel’s most unusual proposals was that humanoids lived in cities in the craters of the Moon and populated the surface of every other celestial body. In 1835 a New York newspaper published a satirical series of articles aimed at those who still promoted such ideas. The paper described a Moon populated with fantastical creatures, observations they attributed to Herschel’s son, John, himself a successful astronomer. But many readers missed the sarcasm, and the Great Moon Hoax became one of the best-known newspaper hoaxes of all time.

The fame of the 40-foot telescope made it a visual rallying point for discussions about religion and science. According to Richard Holmes, many prominent atheists, including Pierre-Simon Laplace and Jerome Lalande, increasingly used Herschel’s papers about nebulae and the origins of stars to justify an alternative genesis story that did not require God. These theories were initially met with fierce resistance; even Herschel backed away from his assertions about the nature and distance of nebulae, a move that, Holmes says, “may have partly reflected a growing fear of radical science in England.”

To Herschel the telescope was ultimately a failure. At first he believed it could be a model for future telescopes, but in 1815 he published a paper describing his disappointment in detail. A few years later he officially retired it from use. Herschel was getting too old to navigate the telescope’s massive superstructure, and falling mirrors had nearly flattened both him and Caroline on multiple occasions.

Meanwhile, Caroline continued her career as one of the world’s first paid female scientists and was awarded a medal by the Royal Astronomical Society for cataloging thousands of nebulae. She moved back to her hometown in Germany soon after William’s death in 1822 and spent the remainder of her healthy years sweeping the sky for new celestial objects. The memoirs she wrote offer great insight into astronomy in Georgian England. Today Caroline Herschel is frequently invoked as an empowering symbol for female scientists.

In 1839, 17 years after William Herschel’s death, the 40-foot telescope was disassembled for fear it would collapse under its own weight. Herschel had long ago advised his son, John, by this time a well-known astronomer in his own right, not to try rebuilding it. The image of the telescope remains on the seal of the Royal Astronomical Society, a symbol that represents a marvel of engineering but a failure of astronomy.

Correction: Descriptions of reflector and refractor telescopes have been updated to better describe how each telescope works.