Who Knew History Could Be So Delicious?

Discovering the history of umami in the Science History Institute’s archives.

Discovering the history of umami in the Science History Institute’s archives.

In the Papers of Georg and Max Bredig at the Science History Institute, there is a group photograph of the University of Leipzig physical chemistry department’s Christmas party from 1900 (above). The majority of the people pictured reflect the demographic that then dominated the field of science—white, European men. But because there is little representation of Asian scientists in this collection, two people stood out to the Bredig digitization team: Japanese chemists Kikunae Ikeda (1864–1936) and Yukichi Osaka (1866–1950).

Upon further research, the team learned there was a history of Japanese chemists who traveled to Europe to study under scientists such as Wilhelm Ostwald and Walther Nernst. They also discovered that Ikeda, who studied with Ostwald in Leipzig from 1899 to 1901, had a surprising legacy: he had identified and synthesized the flavor umami.

Growing up, Ikeda loved dashi, a Japanese soup stock, and he noticed a unique flavor in his favorite childhood food that wasn’t any of the four basic flavors. It wasn’t sweet and it wasn’t salty; it was something more complex. While studying at the University of Leipzig, he also noticed that the tomato-based German dishes had the same savory flavor as Japanese dishes.

A postcard to Georg Bredig from both Japanese and German scientists attending a conference in Kyoto, Japan, 1924.

After returning to Japan, Ikeda became a professor at Tokyo Imperial University. In 1907, while eating seaweed intended to make dashi, he became inspired, if not obsessed, with understanding the unique flavor in kelp and in the tomatoes he’d tasted in Germany, as well as in meats and cheese. He studied the properties of dashi and realized that this flavor was not a combination of sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. No, this was a fifth element.

Ikeda described the flavor in his paper “On the Taste of the Salt of Glutamic Acid,” writing, “Those who pay careful attention to their taste buds will discover in the complex flavor of asparagus, tomatoes, cheese and meat, a common and yet absolutely singular taste which cannot be called sweet, or sour, or salty, or bitter.”

By 1908 Ikeda successfully isolated the amino acid glutamate to which he attributed kelp’s unique savory flavor. He named his discovery “umami,” which means “deliciousness.” Today, umami is considered the fifth basic taste.

According to the Umami Information Center, umami is a mild, subtle taste consisting of three properties: spreading across the tongue, persistence or lingering in the mouth, and promotion of saliva. What exactly does that mean for flavor? Think of savory foods, cooked and cured meat and fish, tomatoes, mushrooms, cheese, fermented foods, and soy sauce.

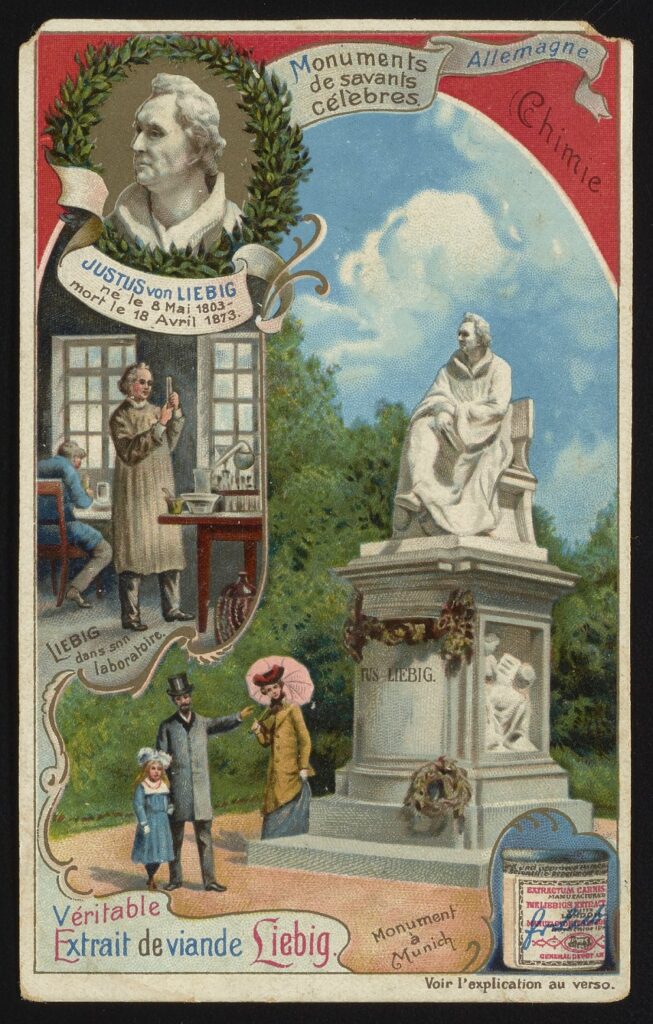

After his discovery, Ikeda wanted more; he wanted to change Japan. While in Germany, Ikeda noticed how much bigger and taller German people were than his fellow Japanese. He was inspired by German chemist Justus von Liebig, who had developed a beef extract as an affordable and nutritious alternative to meat.

Ikeda believed that flavor was the key to improved nutrition and that if he could synthesize this flavor, he would significantly advance nutrition in Japan. In 1908 Ikeda filed a patent for monosodium glutamate, or “MSG,” a seasoning based on glutamate.

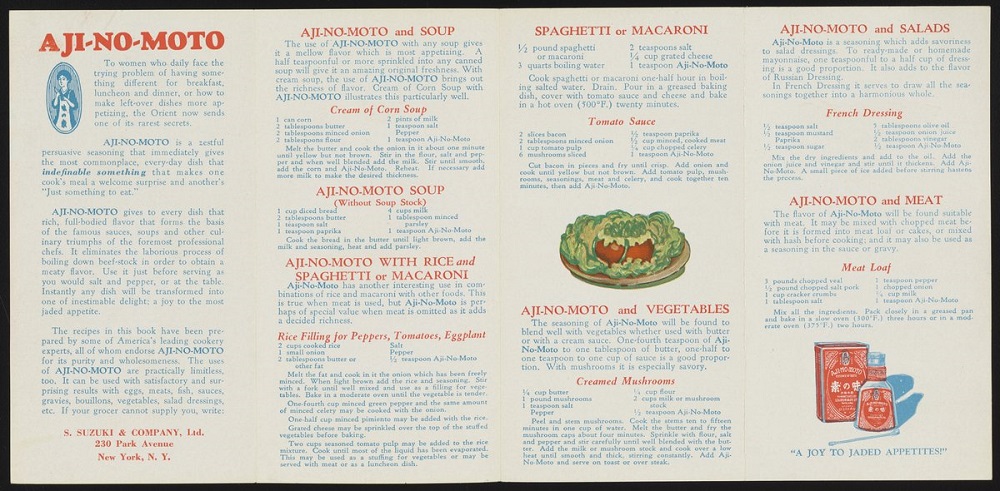

After his patent was approved, he went to Saburosuke Suzuki, then head of Suzuki Pharmaceutical Company, to produce and market MSG. The seasoning was called “Ajinomoto” or “essence of taste.”

The recipes in this 15 Delightful Recipes Prepared in a New Way promotional pamphlet sought to introduce aji-no-moto to a non-Japanese audience, 1930.

MSG became wildly popular in Japan. It was marketed to housewives and recently graduated female students, and eventually became a staple on the emperor’s table. By the 1930s, MSG had found its way to America and became a staple in American cooking. MSG could be found in soups, baby food, and cookbooks.

In the 1960s, as awareness of nutrients, preservatives, and food additives grew, people began taking a closer look at what was put in their food. In 1968 a Chinese American doctor published a letter in the New England Journal of Medicine documenting the adverse effects—including radiating pain in his arms, weakness, and heart palpitations—he noticed every time he ate at a Chinese food restaurant. These effects were attributed to MSG and were called “Chinese restaurant syndrome.”

After a 1969 study reported that mice injected with MSG developed brain damage, the food additive gained a reputation it seemingly couldn’t become free of. Although it was never banned or regulated by the FDA, the American public quickly became averse to MSG in their food, convinced it was toxic.

Recently, Ajinomoto Co., Inc. (today’s name for Suzuki & Co., who began manufacturing MSG in 1909) have begun rebranding their product as an “umami enhancer.” Concurrently, new studies have rejected previous research that MSG causes brain damage. Even mild side effects such as headaches and nausea can only be obtained through consuming extremely large amounts of MSG without food. Ajinomoto is still producing MSG to this day and it is slowly being embraced once again.

In 1985 the Japanese patent office named Ikeda one of the “Top Japanese Great Inventors.” It is safe to say that he made a monumental impact—and it’s all due to a unique and unyielding love of soup.

The Science History Institute’s Othmer Library announces the winners of its 2025 After Hours comic book caption contest.

Collaboration, connection, and critique over pizza.

How to read a book when the pages are out of order.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.