Thinking Outside the (Search) Box

You say “Walchin,” I say “Wallich.” Let’s call the whole thing off.

You say “Walchin,” I say “Wallich.” Let’s call the whole thing off.

I recently spent a month at the Science History Institute as a practicum student working primarily on the Scientific Biographies initiative. The experience was a fantastic one. As an aspiring historian of science and current master of information student at Dalhousie University in Canada, the Institute’s focus and collections represent the perfect intersection of my interests. I spent much of my time in the library, working on biographies and thinking about how information is conveyed to users both digitally and in person.

I started my practicum by trying to familiarize myself with the Institute’s collections—archives, museum objects, and modern and rare books and journals. The goal was to identify possible people and subjects of interest whose stories could contribute to the Institute’s scientific biographies resource. I immediately knew, though, that this would be a tall task. Although my undergraduate education in the history of science had exposed me to many people and many events, I knew that there was far more that I didn’t yet know. I found myself wondering where to begin when I didn’t even know exactly what I was looking for; I needed a research method that would be efficient and useful.

One of the first ways I tried to search was by using the name and subject headings in the Institute’s library catalog and digital collections. This helped me begin to understand the scope of the collections and what I might be able to find (or not find). But if an author or subject of a work was already tagged or their work digitized, then odds are the person or subject was already on someone’s radar. My goal was to identify people and subjects that weren’t.

I turned, then, to bibliographies. You might be familiar with the concept of a bibliography as something that comes at the end of a paper or article, listing the sources an author used to create a work. But bibliographies also exist to document and catalog as much of a subject as possible. Today, bibliographical projects such as IsisCB (for which the Institute’s Judith Kaplan is the current newsletter editor) are often produced by organizations and societies. In the past, published bibliographies were created by individual collectors and scholars.

The Science History Institute’s Othmer Library has many different bibliographies of chemical and alchemical works published before 1900. I decided to go through several volumes of these, figuring works published after 1900 would be better documented or catalogued.

Older bibliographies, like the thick tomes I used, were often created by a private collector in order to document their own collection, as well as related collections they knew of elsewhere.

Sometimes, one bibliography would include a book that another didn’t, even though both volumes tried to capture the same information. This meant that I needed to be diligent in evaluating each bibliography, as each author had their own stylistic quirks, citation styles, and inclusion criteria.

My goal was to note down citations to any works that were written by a woman or an author from outside the United States and Europe. There are several limitations to this, of course. First, many citations did not include an author’s full name or any name, and second, this method relied on my being able to identify traditionally feminine names—and I learned quickly that many names I expected to be feminine are not: Margarethus / Margareti Verloren, for example, is a man. I was also limited to identifying only non-Euro-American authors whose names had not been Europeanized: while I could identify that Ibn Sīnā was Arabic, if a non-Euro-American author had a Romanized or “European” name, I could not identify them.

Once I had gone through the bibliographies, I was left with a list of names—mostly of women—who works hadn’t yet been digitized in the Institute’s digital collections. My next goal was to see if the Institute possessed any of these individual’s works. This was where I encountered my next challenge.

Although many of the authors I had found were included in the collections of the Institute, several were not. I had worked through this process by searching by author name in the library’s online catalog. I had a string of successes until I searched for Dorothea Juliana Wallich, a 17th-century alchemist. Her name appeared in one of the bibliographies I’d consulted, but not in a second. When I searched for her in the library catalog, her name didn’t appear. This wouldn’t have surprised me, since I was used to searching through non-standardized resources, but it hadn’t happened in any of the other searches I had made.

Whether it was premonition or instinct, I thought to myself that perhaps her name had been misspelled. But Wallich published several books, and with much more obscure works held by the Othmer Library, I figured the odds of the library not having works by her were low.

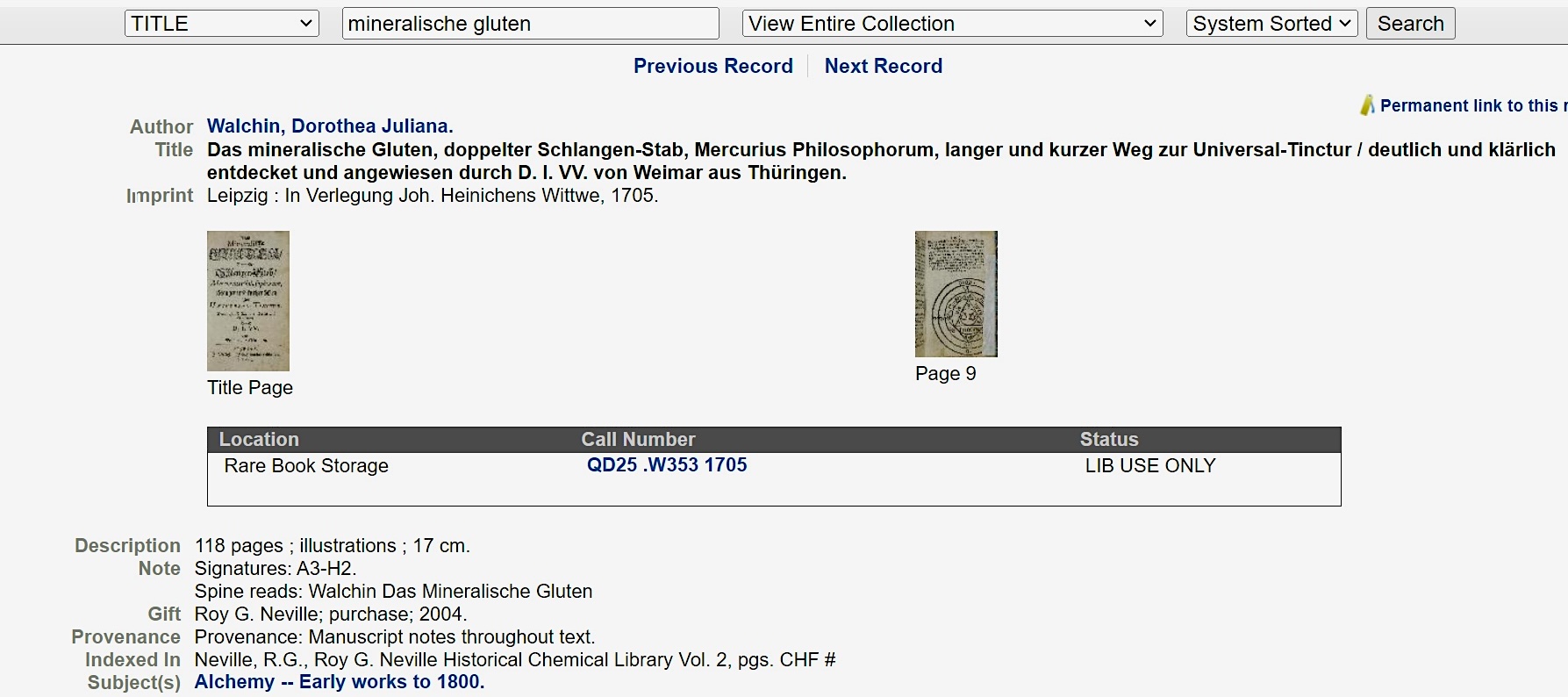

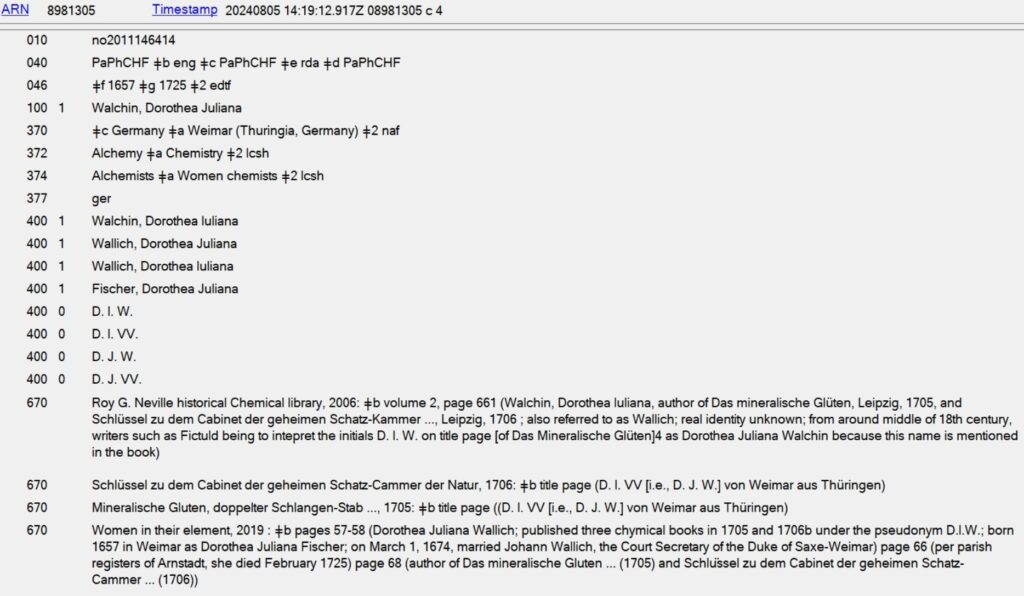

So I searched instead for the title of her book, Das mineralische Gluten. It showed up! Indeed, as I had thought, the Othmer Library did have her works, but her last name came up as “Walchin” instead of “Wallich.” According to the catalog record, her name was even listed as “Walchin” on the book’s spine.

I double-checked that the bibliography I had used did indeed say ”Wallich.” Some research online led me to the understanding that Wallich is the accepted German way of spelling her name. The confusion had stemmed from the fact that she never fully identified herself in her works. When scholars began to study her work and to translate it, at least two different ways to interpret her name appeared: “Wallich” and “Walchin.”

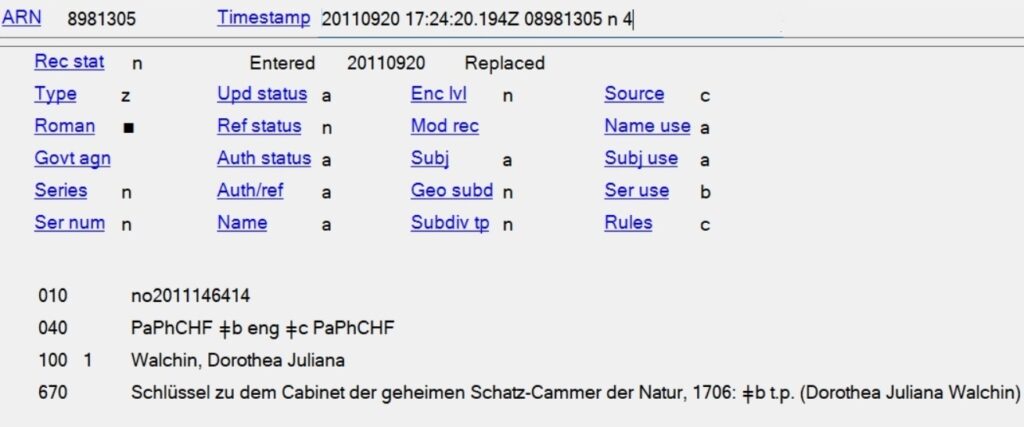

Excited by the idea of being able to change the library database, I went armed with my evidence to the library desk, where I laid out my argument for why I thought that the author’s name on the record needed to be changed from “Walchin” to “Wallich.”

I quickly learned that changing an author’s name in the library database is no small feat. Conversations behind the scenes needed to happen and corroboration of the name also had to be done.

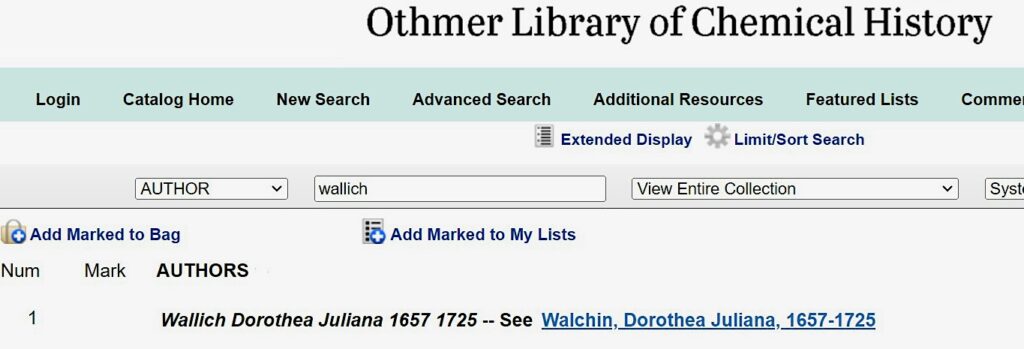

In the end, while her name heading couldn’t be changed, an entry for the “Wallich” form of her name was added to her name record. This means that now, if you do an author search for “Wallich,” you will be redirected to “Walchin” and will find the works written by this impressive 17th-century woman.

It turns out that the name form “Walchin” came from another bibliography, one I hadn’t consulted but which was used when her works had first been entered into the catalog. This brief adventure is a reminder that information is imperfect: it relies on humans to make decisions, to transcribe, to code, and to catalog.

So the next time you think that something doesn’t seem to exist, consider thinking outside the (search) box.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.