There Are More Fish in the C

The CD drive, that is. Meet some of our newest born-digital collections.

The CD drive, that is. Meet some of our newest born-digital collections.

Welcome to Storage Media Speed Dating! This is a lighthearted new series in which we quickly get to know some of the digital storage media in our archives—their likes, their dislikes, and the kinds of stories they tell.

I’m your host, Sarah, the digital preservation archivist at the Science History Institute. My job includes managing all the born-digital historical materials in our archives. Born-digital materials are materials created with a computer that require a computer to access them, as opposed to paper-based materials or most analog materials, which you can read or interpret without needing any additional technology.

Think about the difference between getting information from a book—which you can look at and understand even if it’s 500 years old—and trying to get information off a CD-ROM from 1992, which may require software, operating systems, and hardware that are all obsolete today. In short, born-digital archives are really complicated and every storage format (not to mention file format) has particular needs and requirements for access and care.

Now let’s get to know the beautiful, messy variety of historical digital storage methods on Storage Media Speed Dating!

Today’s contestant is…

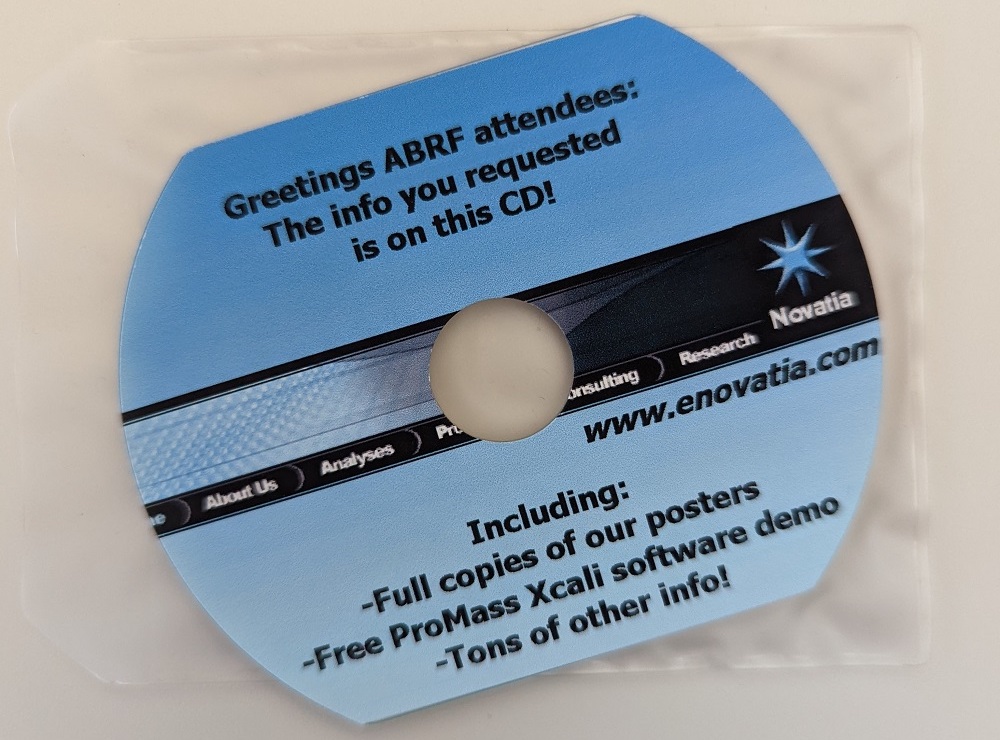

A business card shaped CD made by Novatia, LLC.

Name: Shaped Compact Disk

Birthday: Mid-1990s

Likes: CD drives with spindles, brands and musicians with quirky marketing gimmicks

Dislikes: Tray or slot CD drives, large amounts of data

Shaped CDs can contain software, audio files that you can play in a CD player, or data that you can access on a computer such as image files, PDFs, or spreadsheets. Their physical shape can get pretty elaborate! This thread has some great photos of shaped CDs; my favorite is the one shaped like French fries that Burger King inexplicably released in the mid-1990s.

The catch (sometimes literally) is their bananas (also sometimes literally!) shape. A computer reads a CD by spinning the disk, pointing a laser at its shiny underside, and detecting which extremely small spots reflect the light back and which don’t. This reflection/no reflection—or yes/no distinction—is read as binary code, which a computer translates into files such as a song, PDF, or digital photograph.

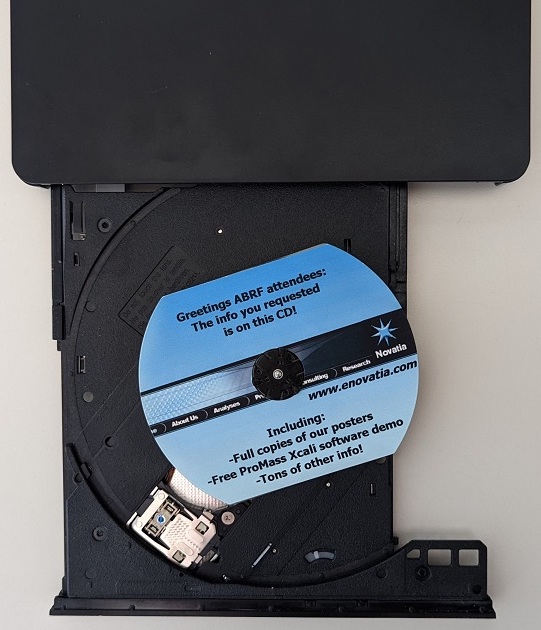

The shaped CD safely tucked into a disk drive with a spindle.

For a more in-depth look at how CDs work, read “Care and Handling of CDs and DVDs: A Guide for Librarians and Archivists,” a thorough and still relevant guide created by the Council on Library and Information Resources in 2003.

Because shaped CDs can have some really asymmetrical edges, you can’t put them into a tray or a slot CD drive and expect them to spin smoothly without a center anchor point to spin around. Without a center spindle built into the disk drive tray, your shaped CD might not move at all, it might get stuck in your machine, or (worst of all) it might rattle around, making horrifying noises and damaging the disk irrevocably so that data is lost.

The business card is the most popular form of shaped CD, and businesses still use them to advertise products and services. They’re easy to distribute and simple to pop into your pocket or bag (and forget about), just like a paper business card.

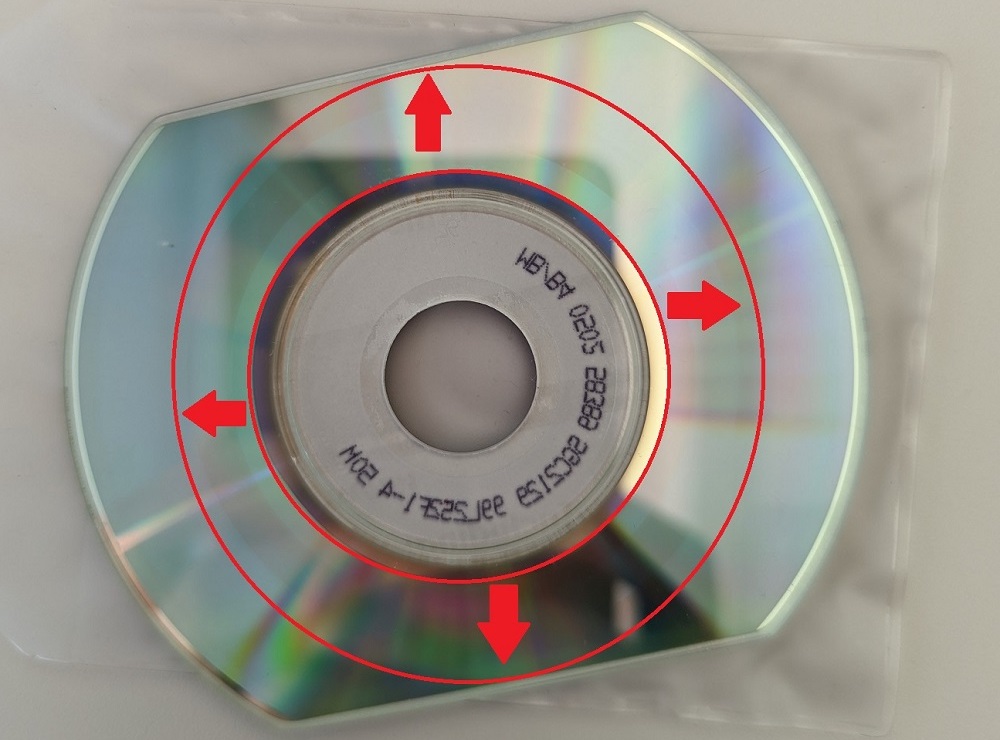

But data is written onto CDs in circles starting from the spindle and moving outward, so shaped CDs can only contain as much data as can be written in complete, concentric circles. In other words, only the area from the center hole out to the red circle on the CD below can contain data. This particular CD contains only 15MB of files.

Only the area between the red circles on this shaped CD can contain data.

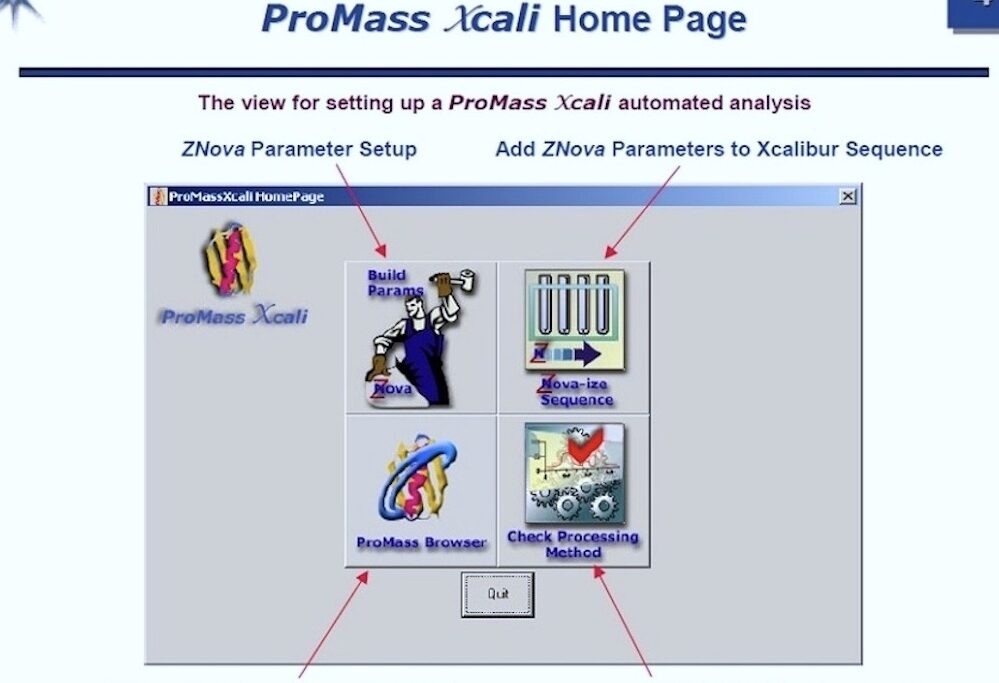

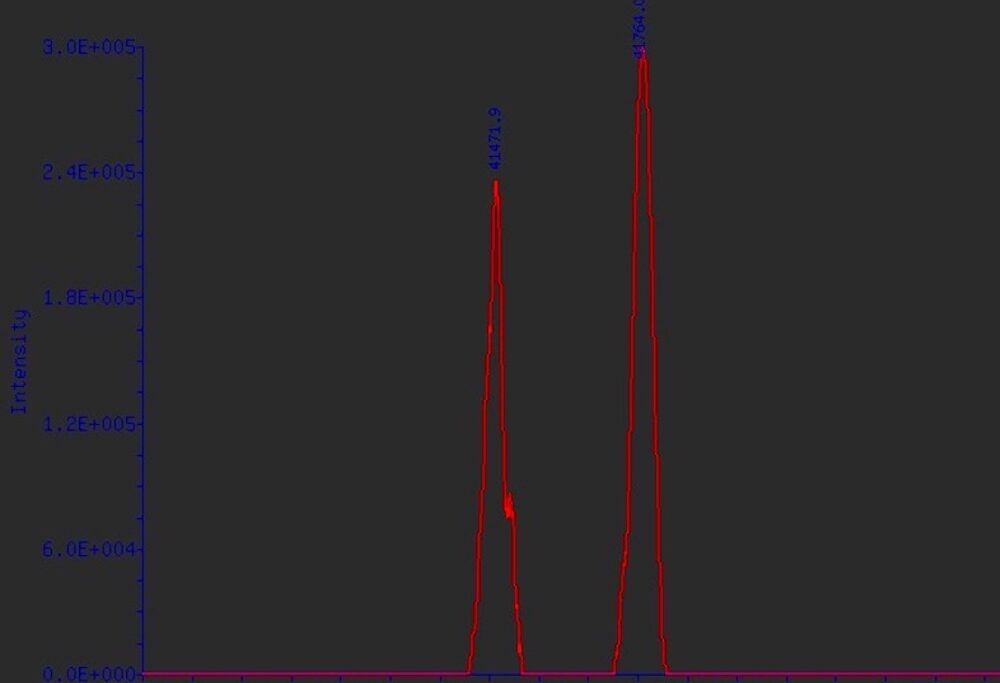

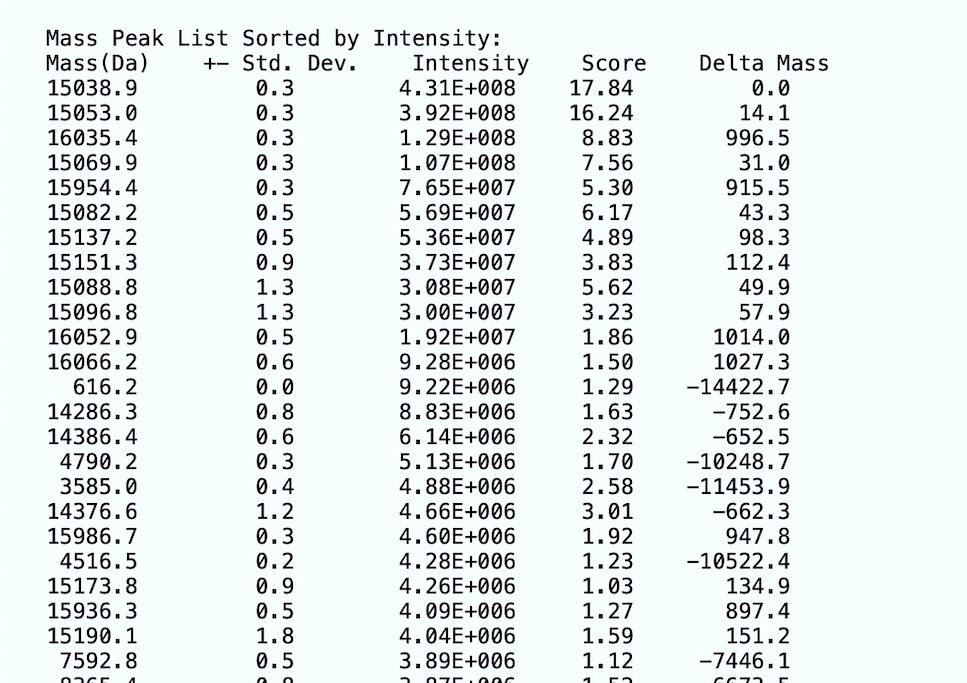

This one was distributed to attendees at the Association of Biomolecular Resource Facilities conference in 2002 by Novatia, a company that provides equipment and support for (among other things) mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. It contains software, data, images, and charts that promote Novatia’s capabilities.

Here are a few screenshots of the files on the disk:

This CD is part of the John B. Fenn Papers here at the Science History Institute. We assume this disk came into our collections with Fenn’s papers because he attended this conference, but without a handwritten note from him, it’s impossible to know for sure.

The audio/visual and born-digital materials in the Fenn Papers are still being processed and preserved, which means I’m still learning what files are on each piece of storage media, safely retrieving the files without altering them, and transferring them to our secure storage. Once that happens, I can add details about the disks and files to the collection guide and work with researchers who want to access them. So for now, you can read about the other paper-based and analog materials in the John B. Fenn Papers in the collection guide.

John Fenn (1917–2010) was an American analytical chemist and Nobel laureate. The collection of his papers mostly covers his career at Yale and includes biographical materials about his life, correspondence with other scientists, scientific research files, papers related to his professional life, and materials around legal proceedings and patents.

If you have questions about this or any other collection in the Science History Institute archives, contact us at reference@sciencehistory.org.

And watch this space to meet our next participant on Storage Media Speed Dating!

sidered the father of modern chemistry, Lavoisier promoted the Chemical Revolution, naming oxygen and helping systematize chemical nomenclature.

Mapping Philadelphia’s industrial past with digital tools.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Explore the history of science behind U.S. efforts to feed schoolchildren with Lunchtime exhibition curator Jesse Smith.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.