The Woman’s World of Pesticides

How killing bugs was gendered.

How killing bugs was gendered.

“Now any woman can transform whole rooms herself . . . No Expert Help Needed!”

As these insecticide-treated wallpaper instructions hint, keeping the home free from bugs was considered woman’s work in 1947. With the rise of new pesticides like DDT in the first half of the 20th century, companies rushed to make products that adapted these chemicals for home use. Men were marketed variations of these products to use in industries such as agriculture, but with the surging popularity of women’s magazines like Good Housekeeping, McCall’s, and Ladies’ Home Journal, housewives also became consumer targets.

The Science History Institute has a large pesticide collection, from cans and diffusers to promotional videos. This collection also contains a rich archive of advertisements that prominently feature women using these chemicals. What stories do these images tell? This ephemera offers a unique perspective into the relationship between pesticides and women’s domestic labor. The marketing of these new household products sheds light on how keeping a home pest-free was depicted, paradoxically, as both essential and trivial work because it was managed by women.

People, of course, have always sought new methods to rid their homes of pests. Early modern recipe books, like this 15th-century Italian manuscript, offer directions for concocting pastes and powders believed to eliminate vermin such as fleas, which irritated humans and pets alike. During the 19th and 20th centuries, however, synthetic pesticides became big business as pests were firmly linked with zoonotic disease. For example, when malaria transmission was definitively linked to mosquitoes, the U.S. military began large-scale fumigation in order to disinfect troops during World Wars I and II. After being deployed in conflicts abroad, these novel insecticides were adapted for domestic circulation.

At the same time, housekeeping transformed into a one-woman job. Changes to household technology during these decades softened the hard labor of cleaning. Middle-class homes, however, also became less able to rely on paid and unpaid servants, who were attracted by rising wages in factory and office work. Navigating these shifts, the housewife was increasingly the sole arbiter of domestic hygiene.

This 1947 advertisement for Thanite (above) links these military and domestic histories. Thanite was a synthetic pesticide derived from rosin and terpene, two chemicals also used to seal sailing vessels. In the ad, a group of men tend a ship while a solitary woman in heels crouches to spray under a sink. In this visual juxtaposition, the Hercules Powder Company traces Thanite’s development from ship caulking to home use. The comparison exhibits how pesticide companies framed the home as the woman’s frontline, where her savvy chemical use could defend against pests’ militarized health threats.

In another Thanite advertisement for a 1946 issue of Soap & Sanitary Chemicals (above), a woman stands at the ready with her loaded hand sprayer, maintaining eyesight on her target. Wearing a bow, an apron, and a serious look, she demonstrates how killing German cockroaches requires regimented determination. The household is her barracks.

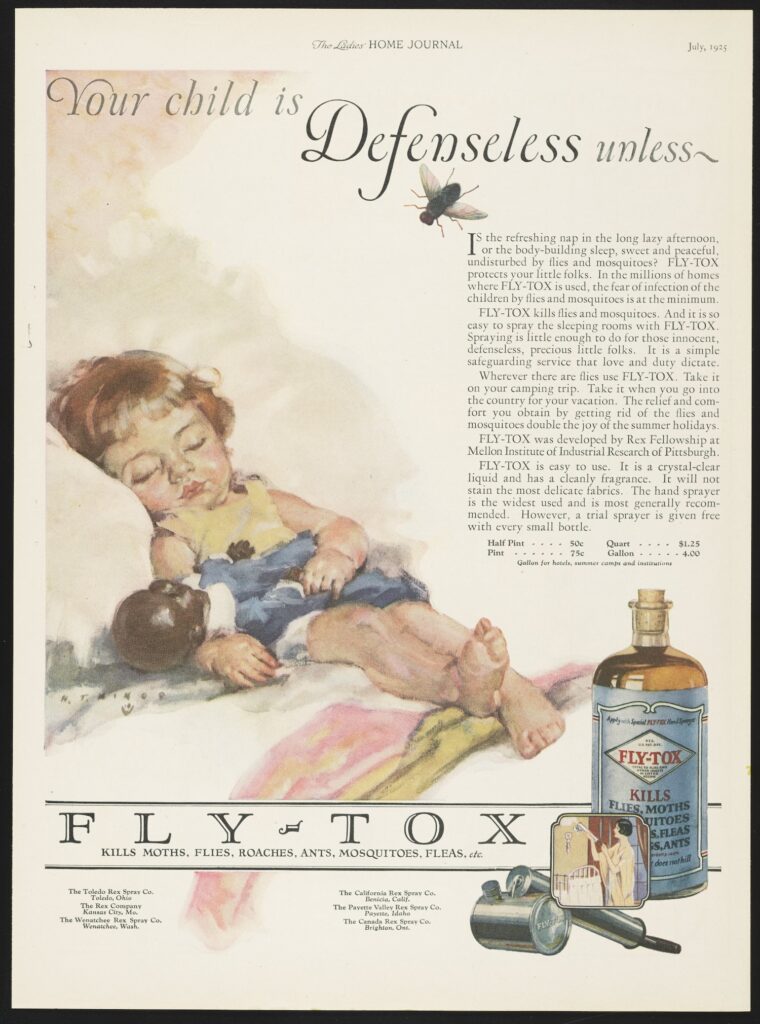

Pests are real threats to health. Insects are often vectors of typhus, yellow fever, and other infectious diseases, but some species were also being investigated as possible causes of other diseases like cancer, as this Saturday Evening Post advertisement features. In addition, childhood mortality rates were significantly higher in the first half of the 20th century. If infected by a disease like malaria, which was not eradicated from the United States until 1951, infants were at especially high risk of severe illness and even death—a fear that shaped advertisers’ visual and rhetorical strategies.

In this 1925 advertisement in Ladies’ Home Journal (above), Fly-Tox depicts a sleeping white child holding a Black baby doll. Above the pair, a monstrous fly hovers below the words “your child is defenseless unless…” This advertisement exemplifies how multiple companies spoke to mothers’ concerns over protecting their children or, in the ad’s melodramatic language, “innocent, defenseless, precious little folks.” How could anyone, the ad nudges, neglect to use insecticides as “a simple safeguarding service that love and duty dictate?”

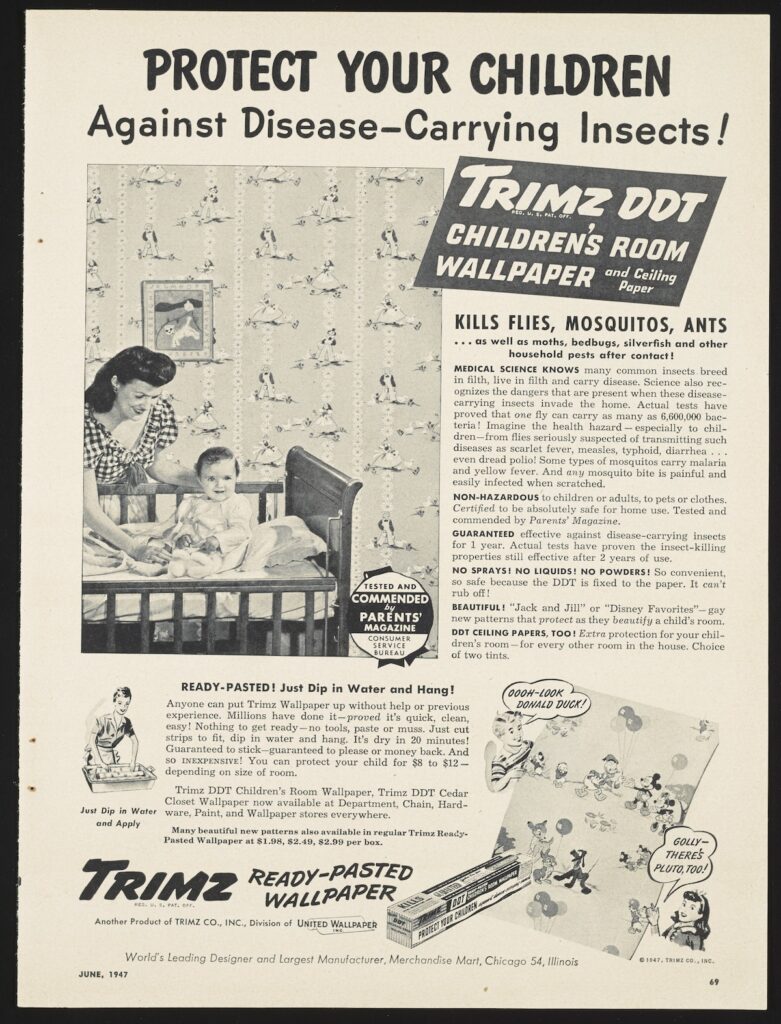

Keeping one’s household vermin-free also meant keeping it sightly. Pesticide advertisements routinely insisted that their products left no stains or residues, but some companies went a step further and crafted a variety of decorative items laced with chemicals. In an advertisement for the magazine Women’s Day (below), Trimz trumpeted that women could “Protect Your Children Against Disease-Carrying Insects!” with its DDT-treated wallpaper that came in both “Jack and Jill” and “Disney Favorites” patterns.

These “gay new patterns that protect as they beautify a child’s room” mark how the judicious use of pesticide was more than just protecting against illness. Pesticide ensured a home’s aesthetic value.

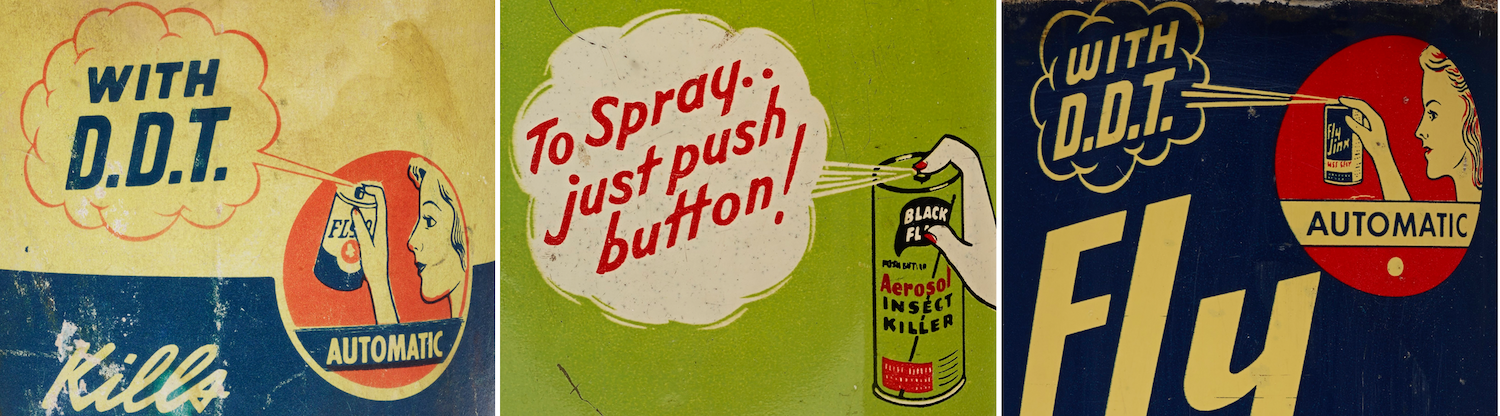

New pesticides became a symbol of modern housekeeping where women could impart a glamorous hygiene. Take, for example, this advertisement for the DDT-based pesticide Black Flag (below) titled “Just press the Button . . . Bugs Drop Dead!”

In the top-right corner, a blonde woman sprays several insects with the newly developed cannister. In three-quarter profile, she has arched brows, full lashes, red lips, and a perfectly manicured index finger pushing the button to release the euphemistically named “magic mist.” In vignettes at the bottom right, another smiling housewife in pearl earrings and a striped dress sprays a living room and a closet alongside languishing pests.

Such advertising downplayed the actual labor of housekeeping. Keeping a home clean is ironically dirty work, and though they were a pricey service in the 1940s, maids—who were disproportionately women of color—were tasked with keeping both their own and other women’s homes pest-free. Indeed, certain tasks such as washing laundry were still frequently outsourced to working women outside the home. The celebration of the elegant white housewife, the diligent mistress of the household, elides how ensuring domestic cleanliness relied on the sweat of many women.

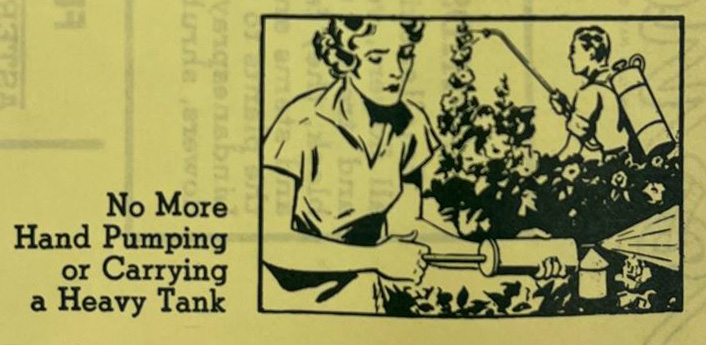

This image of carefree white women killing insects was also meant to celebrate the commercial arrival of aerosol, or the use of pressurized gas to spray liquid droplets. Previously, women used hand sprayers that required laborious pumping to dispense the pesticide.

Now, middle-class women could purchase single-use cans that were promoted as “automatic.” Aerosol cans themselves even included images of women using their products with comfort.

Fly-Go Insect Spray, 1950–1972 (left); Black Flag Aerosol Insect Killer, 1950s (center); Fly Jinx Insect Spray, 1950–1972 (right).

Such imagery boasted how new pesticide technology made women’s labor easier, but it also trivialized their skills. Women’s bespoke knowledge of their own homes was downplayed in the gradual standardization and mechanization of pesticides.

In one unusual 1947 Pennsalt advertisement in Time magazine (above), a housewife stands on stage alongside produce and pets, poultry and livestock—all singing the glories of DDT. In this scene, the housewife is rendered into yet another valuable commodity that industrial pesticide protects, that DDT makes “good.”

As these advertisements’ conflicting images demonstrate, women have long histories as managers of the household. Masculine assumptions about the value of domestic labor downplayed their knowledge, but women kept homes pest- and disease-free. Alongside these advertisements, women’s magazine subscribers also read articles on the threats of malaria, the biology of insect pests, and of course the risks of chemical pesticides—most notoriously DDT.

In other words, housewives did their own research into how to best institute pest management. Women did transform whole rooms themselves because they were the experts of their household.

Featured image: Detail of Thanite for Household Sprays: Improves Quality…Cuts Costs, Hercules Powder Company advertisement, 1944.

What are cookbooks doing in a history of science collection?

More and more digital research tools are helping to answer even the smallest collections questions.

In pursuit of something memorable and meaningless.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.