The Power of a Teacher

How chemistry offered an international path to survival.

How chemistry offered an international path to survival.

Do you have a favorite teacher or professor who inspired you to do your best? Maybe their teaching style resonated with you. Maybe they had a knack for pithy quotes. Or maybe they took a personal interest in your life and went beyond what was required because they believed in your future.

George Rosenkranz found such a mentor in Leopold Ruzicka, winner of the 1939 Nobel Prize in Chemistry and a professor of organic chemistry at ETH (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule) in Zurich, Switzerland.

In his oral history interview of May 17, 1997, now in the Science History Institute’s digital collections, Rosenkranz acknowledged, “Of all my teachers, Ruzicka was the most important.” However, what would become a lifelong friendship began with a few uncertain encounters that left young Rosenkranz feeling like he had failed.

Rosenkranz was a Jewish Hungarian who had been taught in one of Budapest’s top schools. When he graduated in 1933, his parents pressured him to apply to the local Hungarian university. Rosenkranz had his eyes on ETH Zurich for both academic and political reasons, but was worried he wouldn’t have a choice because his parents wanted him to stay close to home.

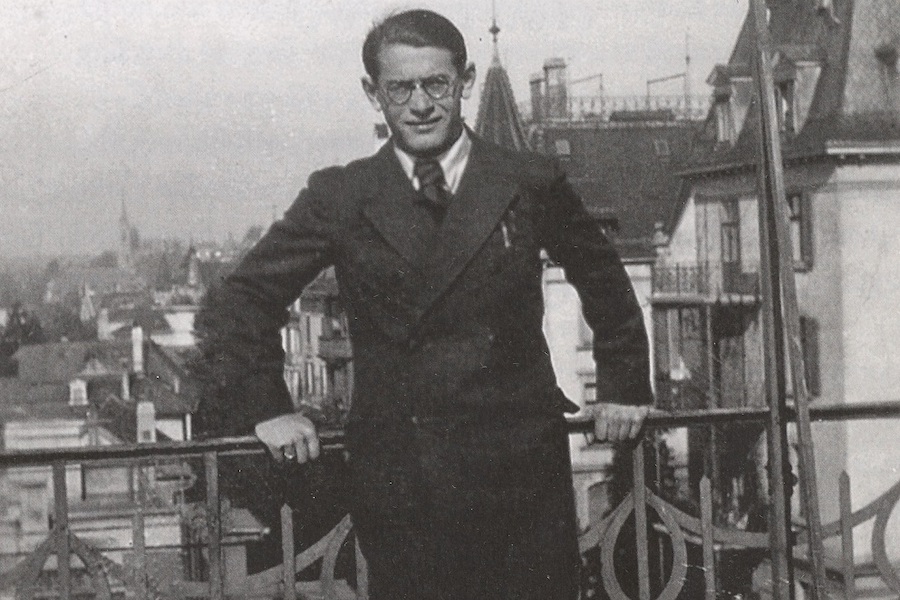

A young George Rosenkranz in Zurich in the 1930s. Reproduced from Arnold Thackray, ed., George and Edith Rosenkranz (Philadelphia: Science History Consultants, 2011).

“We were a Jewish family,” he said, “and in those days, we [in Hungary] had the so-called ‘numerus clausus.’ This meant that only 10 percent of a university’s students could be Jewish. I was afraid that with my good grades, I would be admitted [to the Hungarian university]. My parents insisted that I apply, but I wanted to get away. As you know, Hitler came to power around that time.” Rosenkranz applied and was accepted to both universities. Happily, he convinced his parents that he should accept the offer from ETH Zurich.

But things weren’t perfect in Switzerland either, as the Swiss government restricted employment opportunities for immigrants. “But I managed to support myself,” Rosenkranz noted in his oral history interview. “In Hungary, I had been the junior table-tennis champion, and for a time in Switzerland, I made a living by freelance coaching a table-tennis team in the little town of Adliswil. The other thing that was open to me was theater. I was assigned small roles, which gave me an indirect income. We weren’t paid in cash—that was forbidden—but we had access to theater tickets, which we could then convert into income.”

To financially support his work in the lab, Rosenkranz practiced his tennis and worked in the theater at night. The first time Rosenkranz met Ruzicka outside of class Rosenkranz was dressed in his tennis outfit. He greeted his elder politely as “Herr Professor,” but Ruzicka was unimpressed. He assumed that Rosenkranz must be underworked if he was playing tennis instead of researching in the lab. While most students were assigned a 4-step synthesis process, Ruzicka assigned Rosenkranz an 18-step synthesis that he could not finish before the final exam. “I didn’t finish,” Rosenkranz reflected. “I thought I had blown it.”

Then one night at the theater, when Rosenkranz was made up for his role in a play, he noticed Professor Ruzicka in the third row.

Ruzicka gave Rosenkranz a comfortable salary on the condition that he quit the theater, and so the college student was able to turn his full attention to the laboratory. Ruzicka worked hard to protect the Jewish students and colleagues in his network, helping to secure employment for them outside of Switzerland. Rosenkranz noted that Ruzicka postponed all his exams while the Nazis were in power in Germany because he knew that Rosenkranz would have to leave Switzerland as soon as he finished his studies.

As the war raged across Europe and Jewish scientists struggled to survive through professional positions, Ruzicka secured his student a chair to teach organic chemistry at the University of Quito. Rosenkranz obtained a visa for Ecuador and left Europe in October 1941. His parents understood but were disappointed. They would not talk with their son for four years.

But the 25-year-old would never make it to Ecuador, as the attack on Pearl Harbor destabilized his plans. His ship stopped in Cuba when President Fulgencio Batista decreed that all refugees could remain and work in Cuba with the same rights as Cuban citizens, apart from the right to vote. Rosenkranz decided to stay and worked as a chemist in a pharmaceutical laboratory in Havana. He became skilled in pharmacology, toxicology, and biochemistry, synthesizing new compounds that were used to treat patients in local hospitals.

Yet professional life in Cuba wasn’t satisfying for Rosenkranz. He began corresponding with Ruzicka to tell him that the education he received at ETH Zurich hadn’t prepared him for the large-scale chemical production he was expected to perform in Cuba. Ruzicka, tough as usual, replied that no one told him to have that type of life. Rosenkranz’s opportunities were limited at that moment, but he remained open to future possibilities.

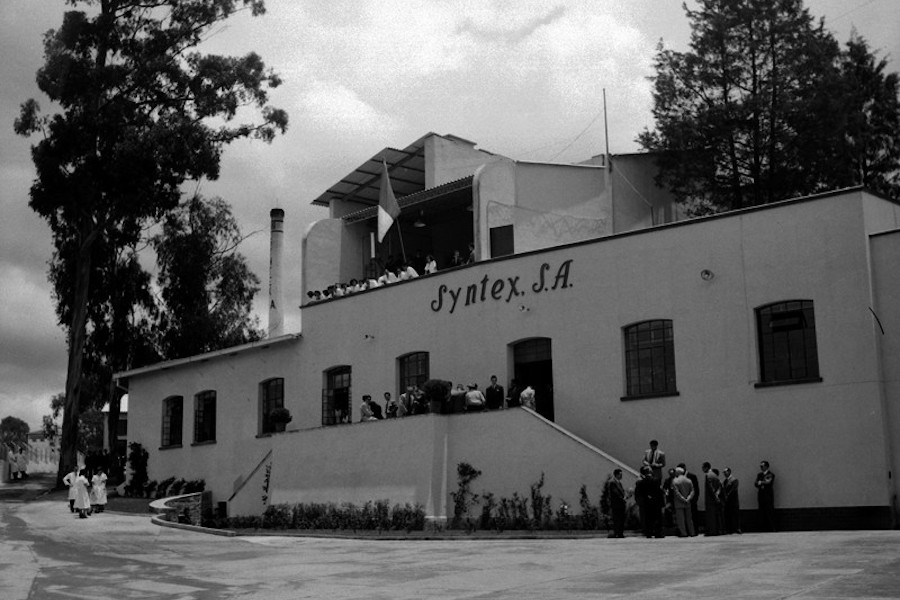

Façade of Syntex laboratories in Mexico, 1952.

It was a phone call one day in 1945 from a fellow Hungarian visiting Cuba that changed Rosenkranz’s life. He was invited to interview with a Mexican pharmaceutical firm, which resulted in a job offer that he accepted. He married his wife Edith, a fellow expat he met in Cuba, and they moved to Mexico so Rosenkranz could take a job working on sex hormones with the chemical company Syntex (a portmanteau of “synthesis” and “Mexico”).

Unlike the island of Cuba, Mexico was the ideal place for this research because the country had an abundance of raw materials. By this time, U.S. chemist Russell Marker had pioneered a method for extracting steroids from wild Mexican yams to manufacture the hormone progesterone. While Rosenkranz had known about this method, he had trouble reproducing it in Cuba. The yams there were edible, suggesting they did not contain high enough quantities of the necessary saponins or sapogenins for sex hormone preparations.

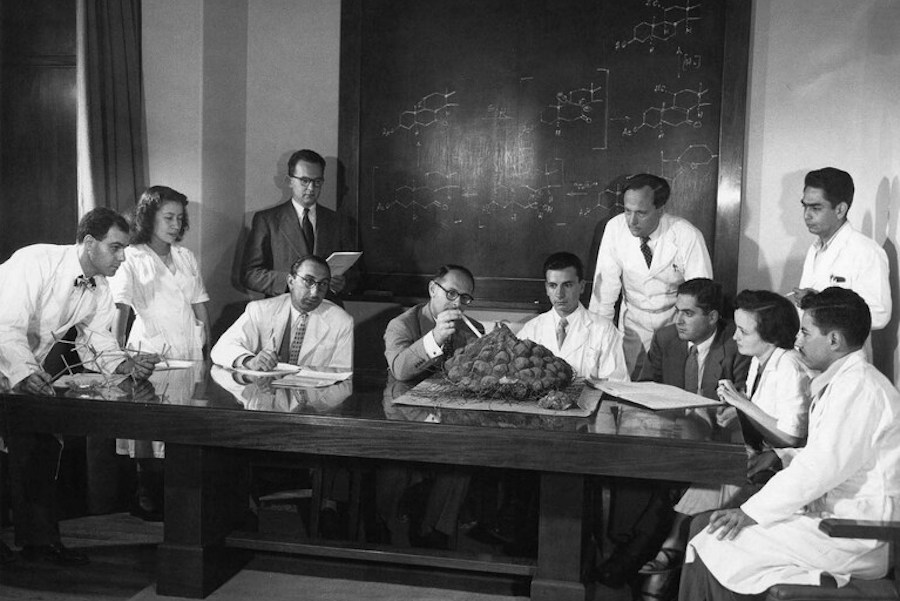

With access to raw materials and a dozen laboratory assistants—eight of whom were women—Rosenkranz worked to grow Syntex into an international success. He also started a PhD program and actively recruited the bright chemists he knew, including Carl Djerassi, the Austrian Bulgarian chemist of Jewish descent (whose oral history is also in the Institute’s digital collections).

Together with their team they raced to develop a new synthesis of cortisone and later a new form of progestin, resulting in the first successful birth control pill. Rosenkranz went on to secure more than 150 patents and to publish more than 300 research articles on steroid hormones.

George Rosenkranz, center, with colleagues and the barbasco yams that served as a source material for steroids.

Rosenkranz’s extraordinary story is one of 70 featured in our Immigration and Innovation Oral History project, which was made possible through a generous grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, a statutory body affiliated with the National Archives and Records Administration. Like many other immigrant scientists in this collection, Rosenkranz had to find creative ways to fund his research and relied on personal and professional networks to help him survive and escape persecution.

While Rosenkranz credits Ruzicka for shaping him into a talented and successful chemist, he did acknowledge one place where he did not follow his favorite teacher’s advice. When Rosenkranz first left Switzerland, Ruzicka said, “I wish you all the best. I know you’re going to do good things in your life. There is one thing, one bit of advice, that I would leave you, which is: Don’t touch steroids with a 10-foot pole, because everything that can be done has been done already.”

Here, of course, Ruzicka was wrong.

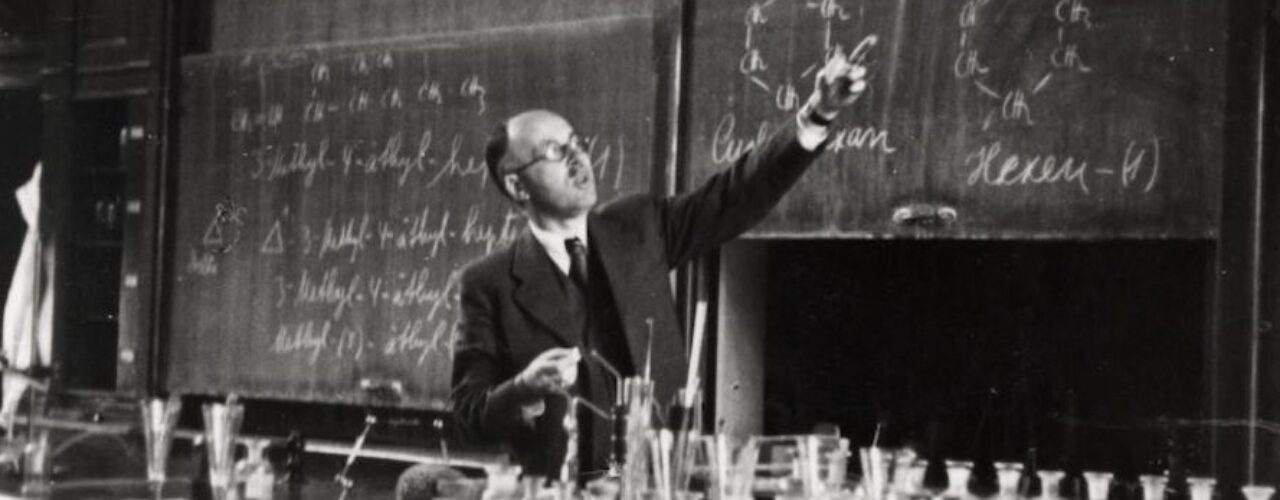

Featured image: George Rosenkranz’s teacher and mentor, Leopold Ruzicka, lecturing at ETH Zurich, 1911. Unknown photographer, Portr-15226, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.