The Nuclear Family

Two instruments evoke memories of being a child during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Two instruments evoke memories of being a child during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Family radiation: Sometimes a startling juxtaposition of two words can summon a powerful historical moment. The Family Radiation Measurement Kit evokes the domesticity and dread that American families experienced as they pondered life in a fallout shelter during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Chemist and entrepreneur Barney Heller donated his family’s radiation measurement kit to the Science History Institute in January 2024. His childhood memories electrify two instruments that thankfully never came out of their box.

Heller was a child of the Cold War. He was 8 years old during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, when the U.S. and Soviet Union came close to nuclear conflict over the placement of Soviet weapons in Cuba and U.S. missiles in Turkey. His parents had met while they were stationed in a Navy hospital in Japan during the Korean War. His father was an orthopedist; his mother a nurse.

The family lived in Kettering, Ohio, a suburb of Dayton in an area that was a hotbed of nuclear work. Monsanto developed triggers for atomic bombs at Mound Laboratories in nearby Miamisburg. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton was one of the Air Force’s major centers for research and development. The Heller family understood that “Wright-Pat” would surely be a target in any nuclear attack.

Young Barney experienced two kinds of drills at school in first and second grade: tornado drills, in which students moved into the hallways, and air-raid drills, during which they were told to shelter under their desks. “That didn’t make sense to me,” he told me in an interview. Heller remembers wondering how a desk could protect anyone from atomic bombs.

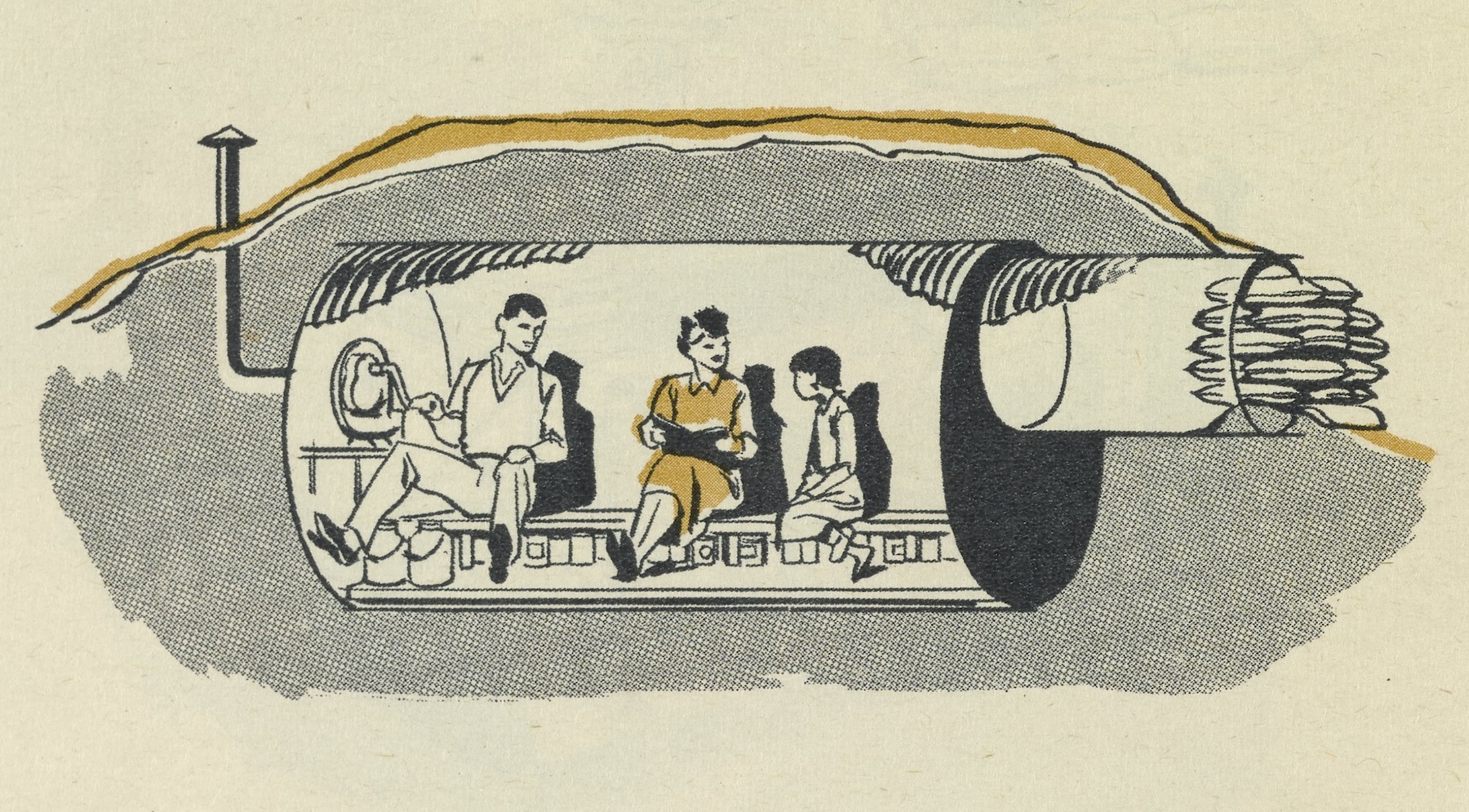

The Heller family had a homebuilt fallout shelter underneath their home, intended as a retreat in which to wait out the radioactive aftermath of a nuclear attack. Heller’s parents were staunch Republicans who hated President Kennedy, but he doesn’t think their politics had much to do with the bomb shelter. It was just a kind of thing that people were building at the time, and it didn’t seem that having a Republican president like Eisenhower or a Democrat like Kennedy influenced the chance of atomic explosions.

The shelter had no door and no roof, just the house’s floor above. It was a small space, maybe 10 feet by 6 feet, with a concrete floor, two bunk beds, and a pair of new mattresses wrapped in paper. Barney remembered asking his parents, “There’s three of us; who’s sleeping on the ground?”

His family practiced going into the shelter once. “We marched down into it. Didn’t faze me at all at the time,” he said, but the significance was clear. “You don’t remember much when you’re 8, but that kind of burned into my mind.”

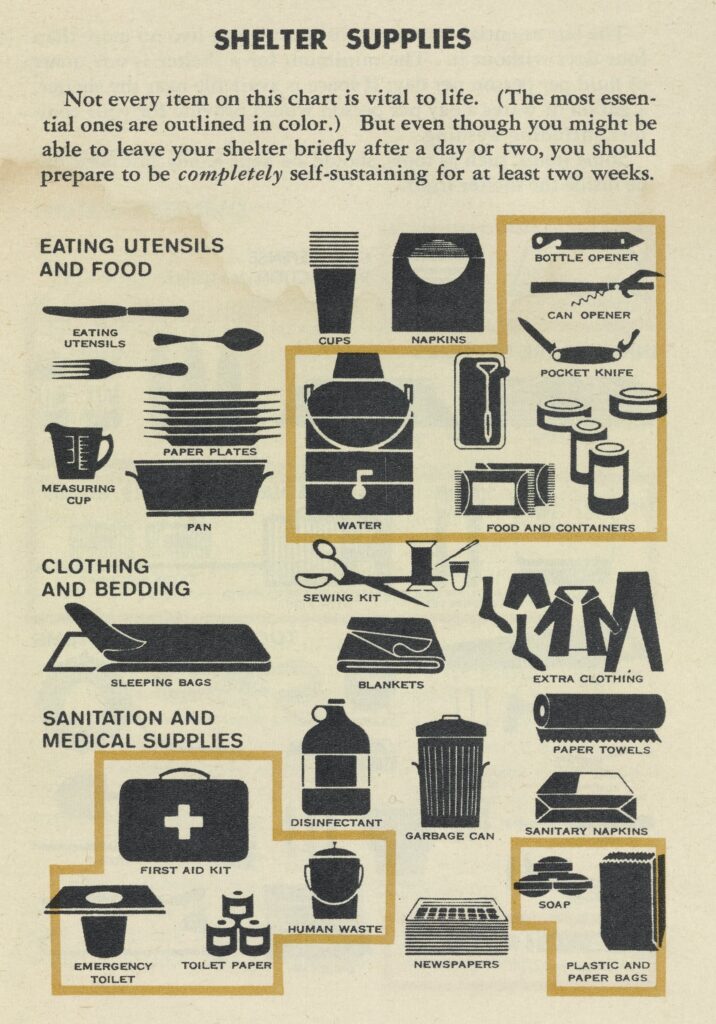

The shelter was stocked with a 5-gallon metal can of water, canned foods, and the family radiation measurement kit. There was a small portable toilet, the thought of using which disturbed Barney. And there wasn’t a television, 8-year-old Barney noticed. “I thought, it’s gonna be pretty boring,” he remembered.

As a kid Barney compared his family’s shelter to those of his friends and neighbors. “Ours wasn’t as fancy as theirs,” he told me. “I figured ours wouldn’t do well in an attack.” One buddy’s shelter had a door and a kind of snorkel, with a hand crank to power a fan to bring in fresh air. Other friends had bomb shelters that were dug into the ground in their backyards.

One neighbor in particular, a general practice doctor, had a shelter that looked better to Heller. Barney suggested his dad should do some “upgrades to keep up with the neighbors,” as he recalled. “No, I’m an orthopedist,” his father said. “I know what I’m doing.”

Other neighbors had board games in their bomb shelter. He asked his mother if they could get some games for their shelter, too. But, he said, “Mother didn’t want to deal with the thought of that at the time.”

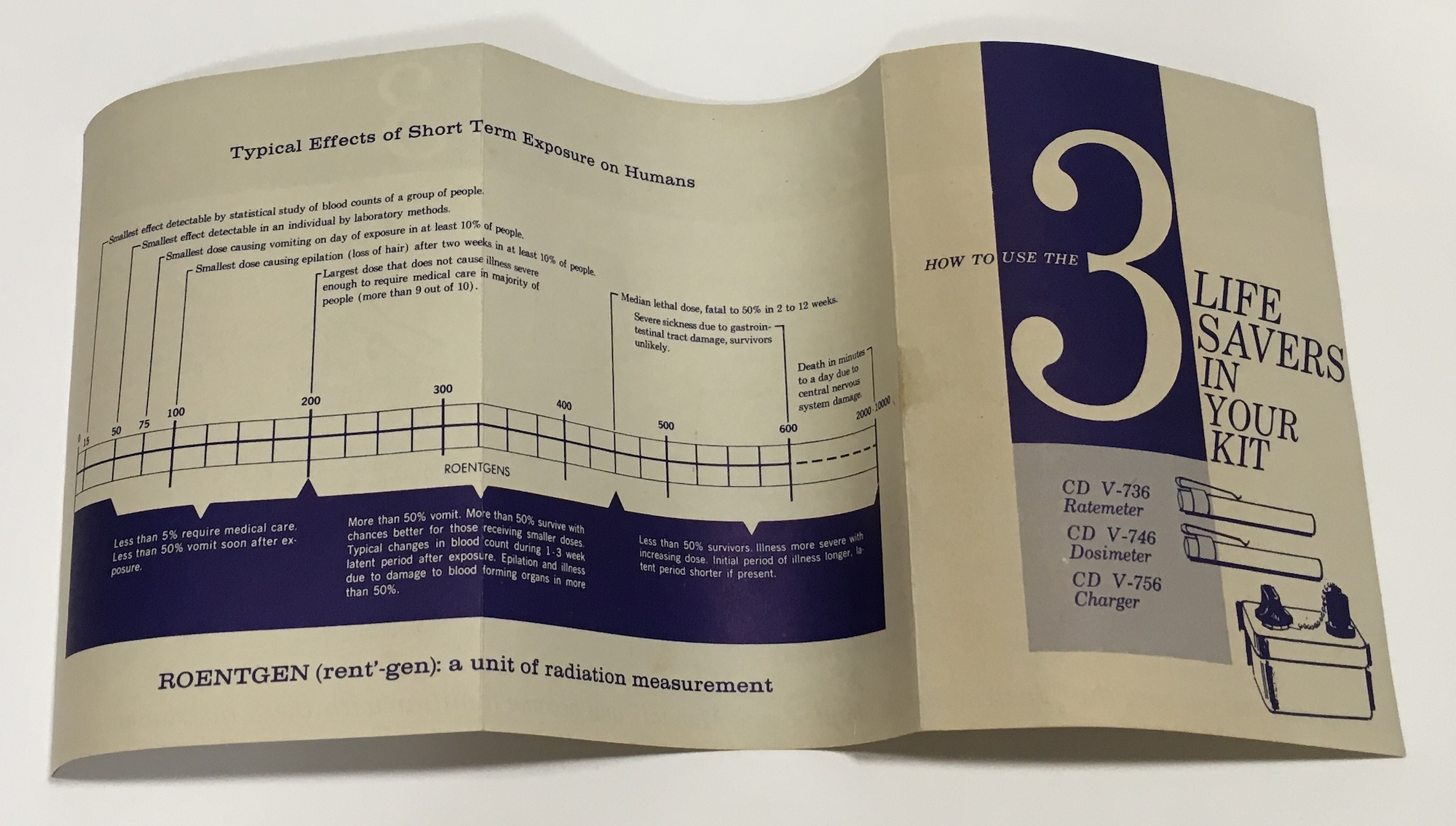

The kit included two pocket-sized instruments. Users started with the ratemeter, which measured radiation exposure in roentgens per hour. If the ratemeter indicated the presence of radiation from nuclear fallout, users switched to the dosimeter to measure cumulative exposure. Both instruments had a pocket clip in case you needed to move outside the shelter. They connected to a battery-powered charger when the time came to read them.

The kit’s instructions include a chart describing the likely effects of various doses of radiation. Exposure to 75 roentgens led to vomiting in 10% of people. A “median lethal dose” of 450 was “fatal to 50% in 2 to 12 weeks,” while more than 2,000 roentgens meant “death in minutes to a day due to central nervous system damage.”

Bendix, a mid-scale defense contractor and scientific instrument manufacturer with a sizable division in Cincinnati, produced these kits between 1960 and 1963. They were one of the first commercially available products enabling home users to gauge radiation exposure. The kit retailed for $24.95 (more than $250 today), though many were included with commercially available bomb shelter kits. Heller surmises a local Bendix salesman sold it, since his father was “very susceptible to salesmen.”

The kit appears to be unused and complete, except for the corroded battery, which the Institute asked Heller to discard before donating. Heller found the kit among his father’s things after he died in 2023 at the age of 99.

Smaller explosions than the one suggested by the bomb shelter introduced young Barney to the charms of chemistry. He recalls that his 7th-grade chemistry teacher taught the class how to combine ammonia and potassium iodide to make contact explosives, like the snap pops now sold in firework shops. It was this hands-on experience that sparked his interest in chemistry. Today, Heller runs the Hardt Chemical company, specializing in concrete, gypsum, and rubber polymerization.

As for the bomb shelter and the radiation measurement kit, Heller remarked that “after the Cuban Missile Crisis, no one talked about it anymore. Then they called it a tornado shelter.”

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.