The ‘Microbe Hunters’ Go to School

What a 1932 special edition of Paul de Kruif’s bestselling book reveals about U.S. science education.

What a 1932 special edition of Paul de Kruif’s bestselling book reveals about U.S. science education.

Lately there has been quite a lot of discussion about the move away from textbook learning—who knows how much longer that epithet will hold recognizable meaning. A 2024 report from the American Historical Society, for instance, found that U.S. teachers are “replacing textbooks with the internet” due to an increasing reliance on educational technologies and the availability of free, open-source materials.

While the technologies involved are fairly new (e.g. electronic platforms for course delivery and program assessment), the impulse to repurpose informal educational materials for classroom instruction is not. We have a nice example of this openness to reuse in the Othmer Library’s collection of Paul de Kruif’s bestseller, Microbe Hunters, a “rumbustious” work of collective biography that has been in continuous publication since 1926.

De Kruif (1890–1971) was a microbiologist who was no stranger to personal controversy. John Steinbeck once described him as a man in “a constant state of emergency.” An army physician, he briefly held research positions at the University of Michigan and with the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. He first turned to popular science writing around 1918 as a means of paying for his complicated love life: de Kruif decided to divorce his first wife, with whom he had two children, in order to marry Elizabeth Barbarian, an assistant in his laboratory, which meant coming up with the money to support two households.

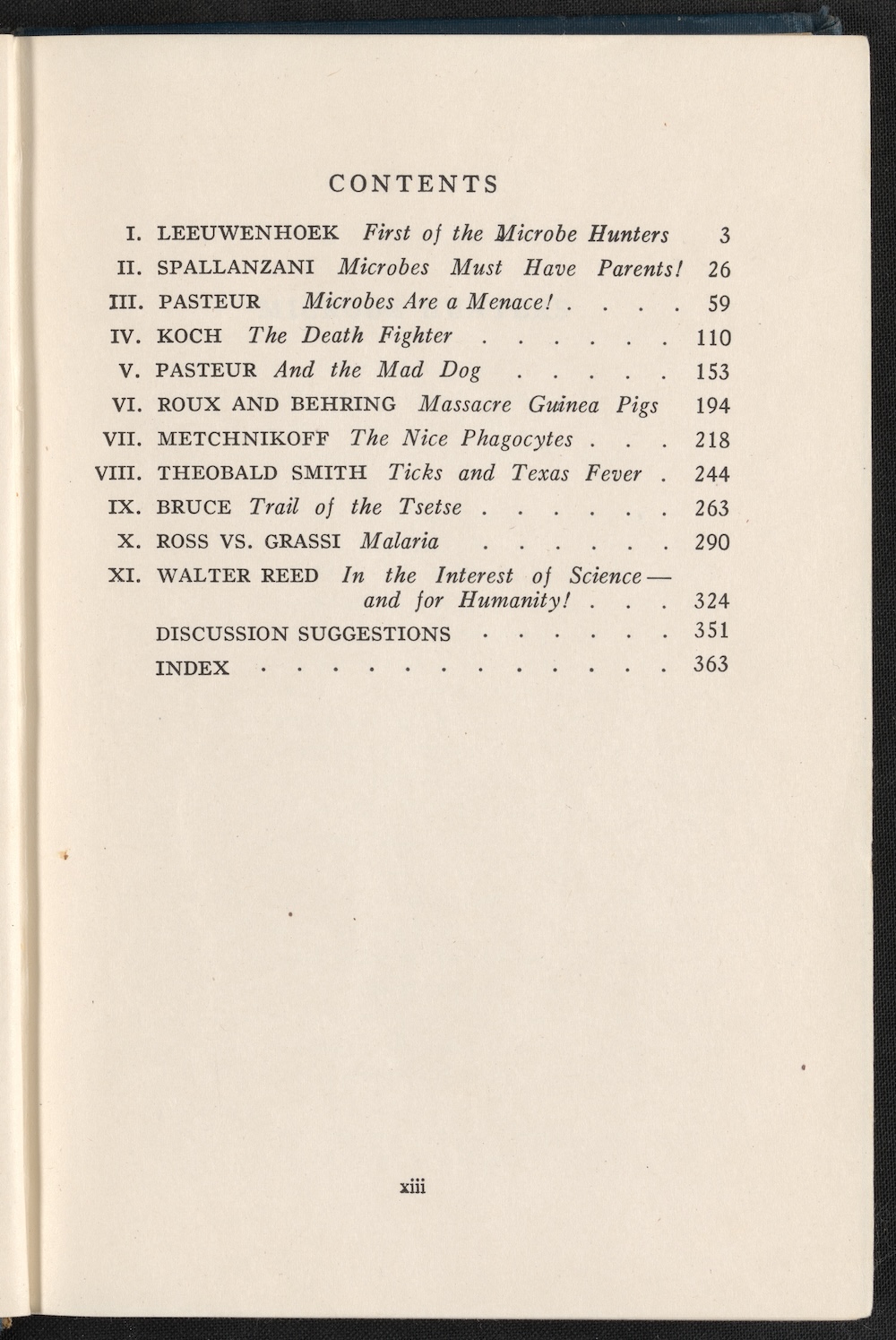

After he was fired from the Rockefeller Institute for publishing satirical portraits of his supervisors in 1922, science writing became his sole means of support and professional activity. Microbe Hunters (1926), which championed the efforts of microbiologists from Antoine van Leeuwenhoek to Walter Reed and Paul Ehrlich, was an immediate success, inspiring generations of curious youth to careers in biology, pharmacology, and public health.

Our newest outdoor exhibition, Sensational Science: A Century of Microbe Hunters, documents the book’s impact on informal learners through testimonials from our oral history collection. The exhibition also features dust jackets and covers from different editions that are as sensational as de Kruif’s prose.

One 1932 edition, sporting a rather plain navy cover, did not make it onto our building’s façade. Though visually unremarkable, this “special edition” offers a fascinating window onto U.S. science education during the interwar period. It was edited and abridged by Harry Greenwood Grover with “the needs of both students and teachers” in mind.

Grover, otherwise known for preparing student editions of literary and theatrical works, had quite a lot to say in his foreword about the state of U.S. education during the 1930s. “[T]he material in the book is of genuine value to students in the twentieth century,” he wrote. “It connects the past, from which the microscope has freed man, to the present, in which it is protecting him. The book is good history, and it is history peculiarly significant to the youth of today because it is a history of the advance of one kind of tremendously important science.” Grover concluded: “[I]t is a thrilling recital of a series of battles told as if they were battles, not as if they were merely experiments.”

Anticipating the concern that such flair might be seen to compromise scientific objectivity, Grover went on to defend the importance of literary studies for students of science. He wrote:

We can meaningfully compare Grover’s advice to recent initiatives that defend the humanities as a tool of “information literacy” using language that is friendly—not opposed—to STEM.

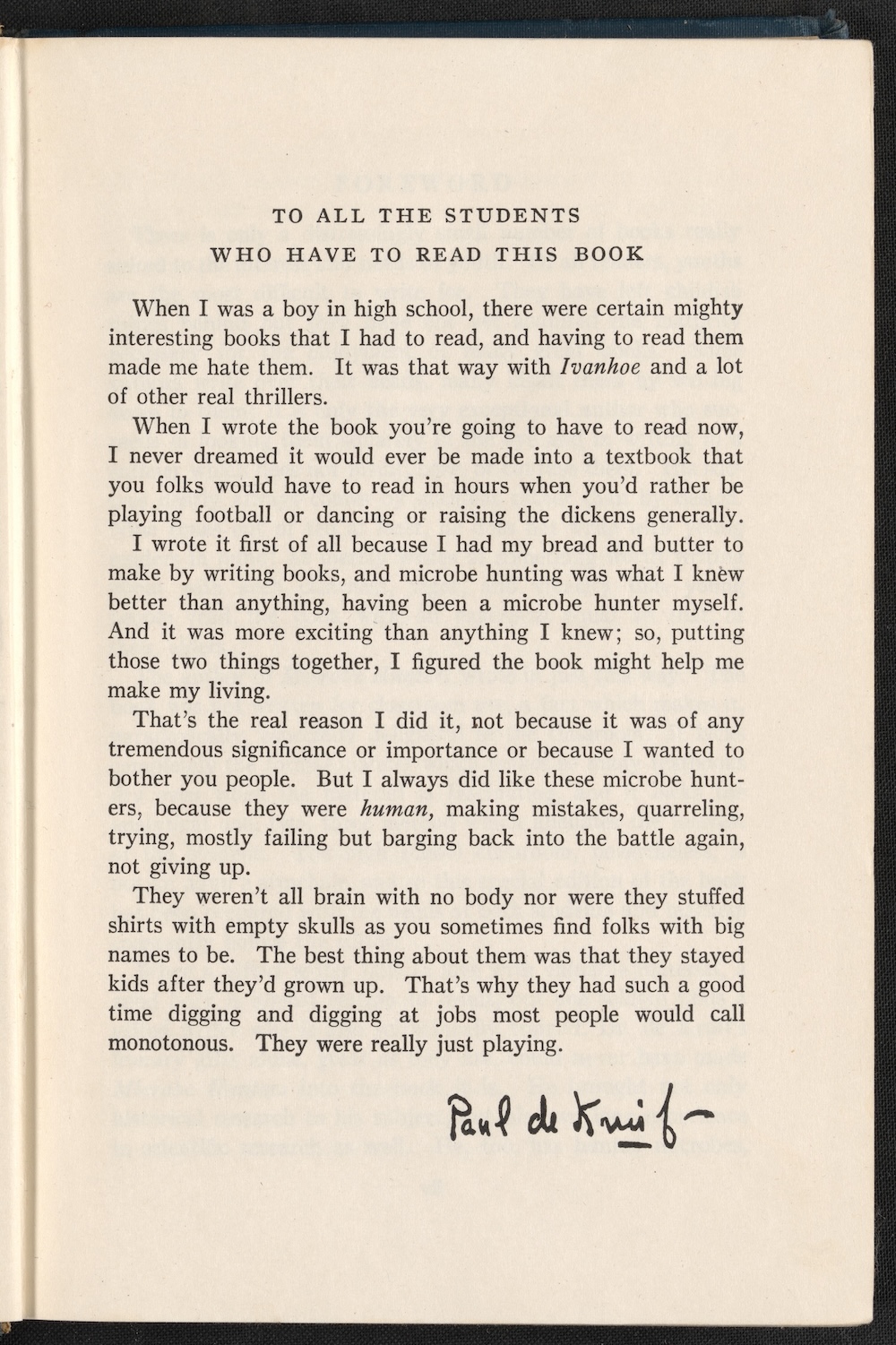

If Grover addressed himself primarily to teachers, de Kruif wanted to say something directly to their students. In his preface to Grover’s 1932 edition, he wrote:

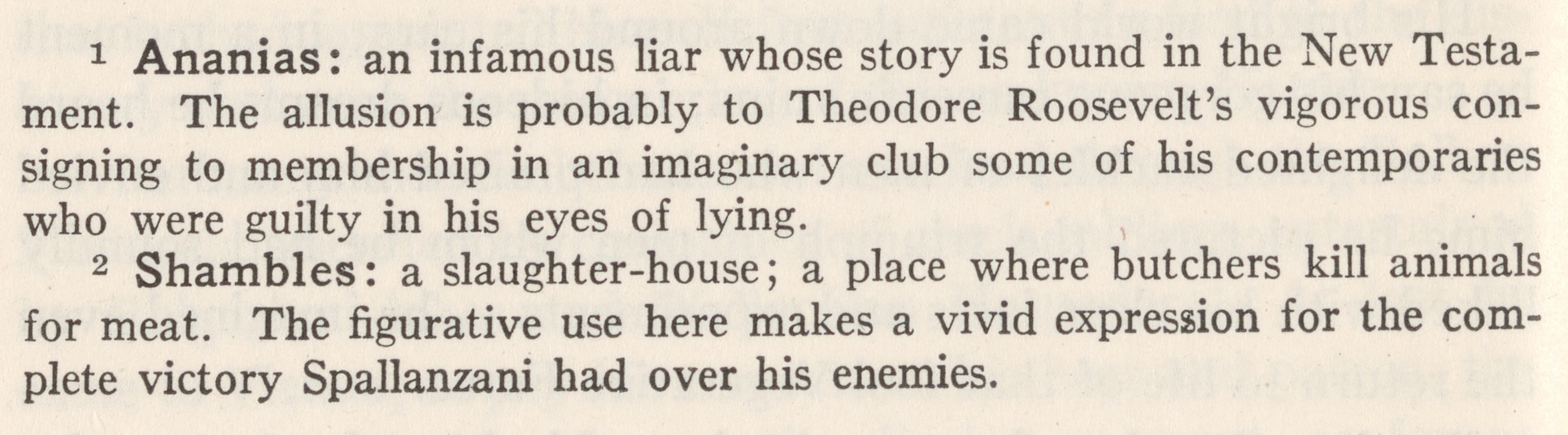

We might conclude from this that de Kruif’s main objective was similar to our own here at the Institute—to “tell the stories behind the science.” But Grover had to build a bridge from that informal learning goal to the needs of formal educators. Though he left de Kruif’s prose mostly untouched, Grover added footnote explainers where he felt U.S. highschoolers might need a bit of extra support or context. These include guides to pronunciation, definitions of Latin terms, biographical sketches of people mentioned in passing, and etymological notes on words like “shambles,” which originally referred to a “slaughter house; a place where butchers kill animals for meat.”

Reading these notes raises questions about what Grover believed students already knew and what they needed to learn. While he assumed students would need some background with respect to the Encyclopédie (an 18th-century collaborative reference work that many have compared to Wikipedia), he thought they would have already known about the Royal Society (an association formed in London in 1660 for “Improving Natural Knowledge”).

He also assumed that they would be able to mentally locate European cities without a map. Curious about how Grover’s expectations might compare to those placed on students today, I ran selections of de Kruif’s text through the Flesch-Kincaid readability formula, a standard tool used by contemporary educators. This yielded scores in the 40s and 50s, indicating that the text was suitable for college graduates.

Grover’s “special edition” of Microbe Hunters also includes appendices with questions for discussion and reading comprehension. Together, they can help us understand what teachers and students might have known and cared about in the interwar period. Supplementing chapter 2 on Lazzaro Spallanzani, Grover asks, “Why does De Kruif make the builders of the cathedral of science synonymous with haters of war? Citizens of the world? Genuine internationalists? What bearing has this suggestion on the problem of promoting world-peace? Is it possible that there would be a real brotherhood of man if all workers in ideas could get together?”

Regarding chapter 8, with a view to reading comprehension, he asks: “What was there in the make-up of the Bureau [of Animal Industry] that made it impossible for Smith to do real free science work? Must tangible results be the test of the work of a government servant?”

And in chapter 11, which concludes this edition of the book, he encourages students to wrestle with a question that may still resonate today: “What do you think about the returns for a service of the kind that Walter Reed gave and that given by a great industrial leader or financier? Which puts the human race further on the road to success—spending millions of men and money in destruction or saving millions of men and money in truth finding?”

All of this is to say one can’t judge a book by its cover. For anyone interested in the adaptation of general-interest materials for classroom use, there are some pretty exhilarating precedents in this outwardly humble book!

How to read a book when the pages are out of order.

An Institute fellow sheds light on an enigmatic trio.

We’re still scratching our heads over how the brain works.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.