The Ants (and Spiders and Roaches) Go Marching

How the creepy crawlies in our collections turned my “Eww” into “Wow!”

How the creepy crawlies in our collections turned my “Eww” into “Wow!”

I hate bugs. I hate them even more now after getting a face full of spiderwebs during my dog’s morning walk a few weeks ago. And yes, I know spiders are technically not bugs—they’re arachnids, plus they eat all the bugs I hate. But still, spiderwebs in the face at 6:30 a.m. is not fun. Picture Kate Capshaw in that scene from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom where she’s covered in giant insects and screaming, “Get ’em off me! Get ’em off me!” That’s pretty much how I reacted, only louder. Just ask my neighbors.

There was also that time an enormous cockroach crawled over the top of my computer monitor—just inches from my face—and I jumped straight up from my chair and ran shrieking down the hall like I was on fire. That was in New York City; I had a similar encounter at a previous job in Philadelphia, and I swear this thing had antennae that were at least 10 inches long (yes, 10 inches!).

Fun fact: if you’re from South Philly (like I am!), it’s pronounced “cock-a-roach.”

My aversion to bugs was reinforced during a recent trip to North Cape May, New Jersey, on the Delaware Bay. Before my husband could even open our beach umbrella, we were attacked by thousands (yes, thousands!) of biting flies. They attacked our poor dog, too. What should have been a perfect beach day was cut short by an annoying (and painful!) flying insect that I’m convinced only exists to ruin people’s vacations.

Left: Detail of Do Roaches Spread Cancer?, an advertisement for Tanglefoot spray, 1926; Right: Detail of Problem…Solution…Result, an advertisement for Hercules Powder Company, 1947.

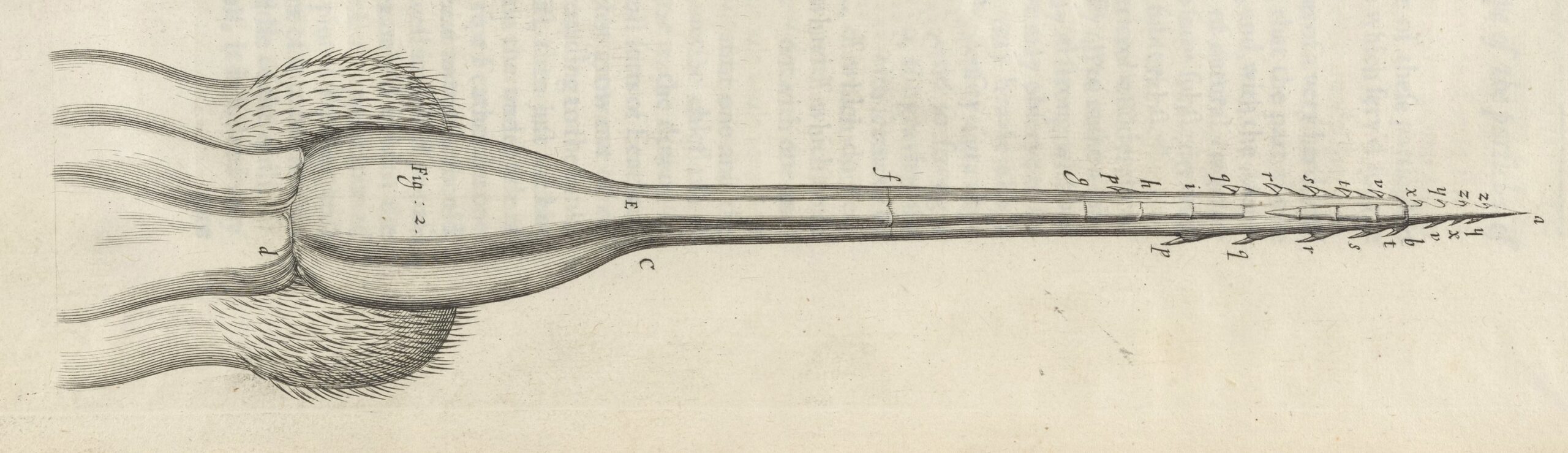

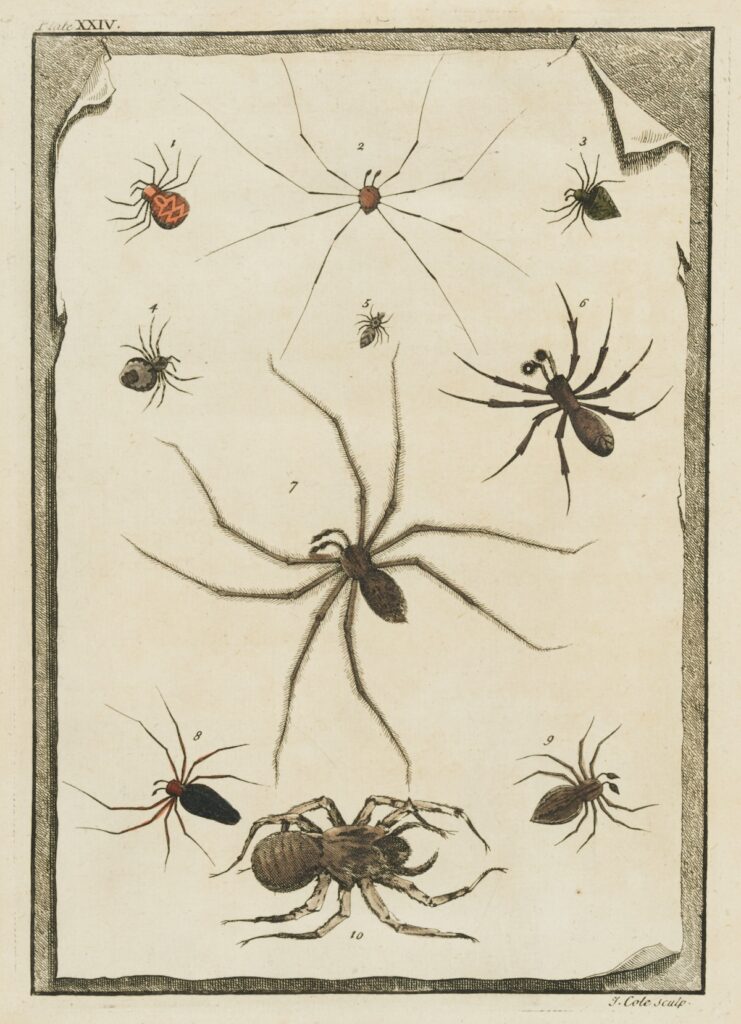

So imagine my surprise when I discovered all the fascinating and sometimes beautiful (yes, beautiful!) creepy crawlies in the Science History Institute’s collections: rare books with intricate engravings of a bee’s stinger, cicada wings, and mosquito larvae; colorful advertisements for pesticides; and even a few illustrations of those pesky spiderwebs.

A search for “insect” in our digital collections (which I did while putting together a bug-themed issue of the Institute’s newsletter) returned more than 500 results, including Micrographia: or, Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses, With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon. But rather than being repulsed while browsing the pages of the 17th-century work, I found myself saying “wow!” more than a few times.

As a bonus, I learned that Micrographia was the first book to include illustrations of the invisible world of insects and plants. It’s also where the term “cell” was coined (as in the basic unit of all life). The groundbreaking volume (a bestseller in 1665!) was written by English scientist Robert Hooke, who engraved all 38 of the copperplates himself using observations from a microscope he designed himself. The detail is stunning.

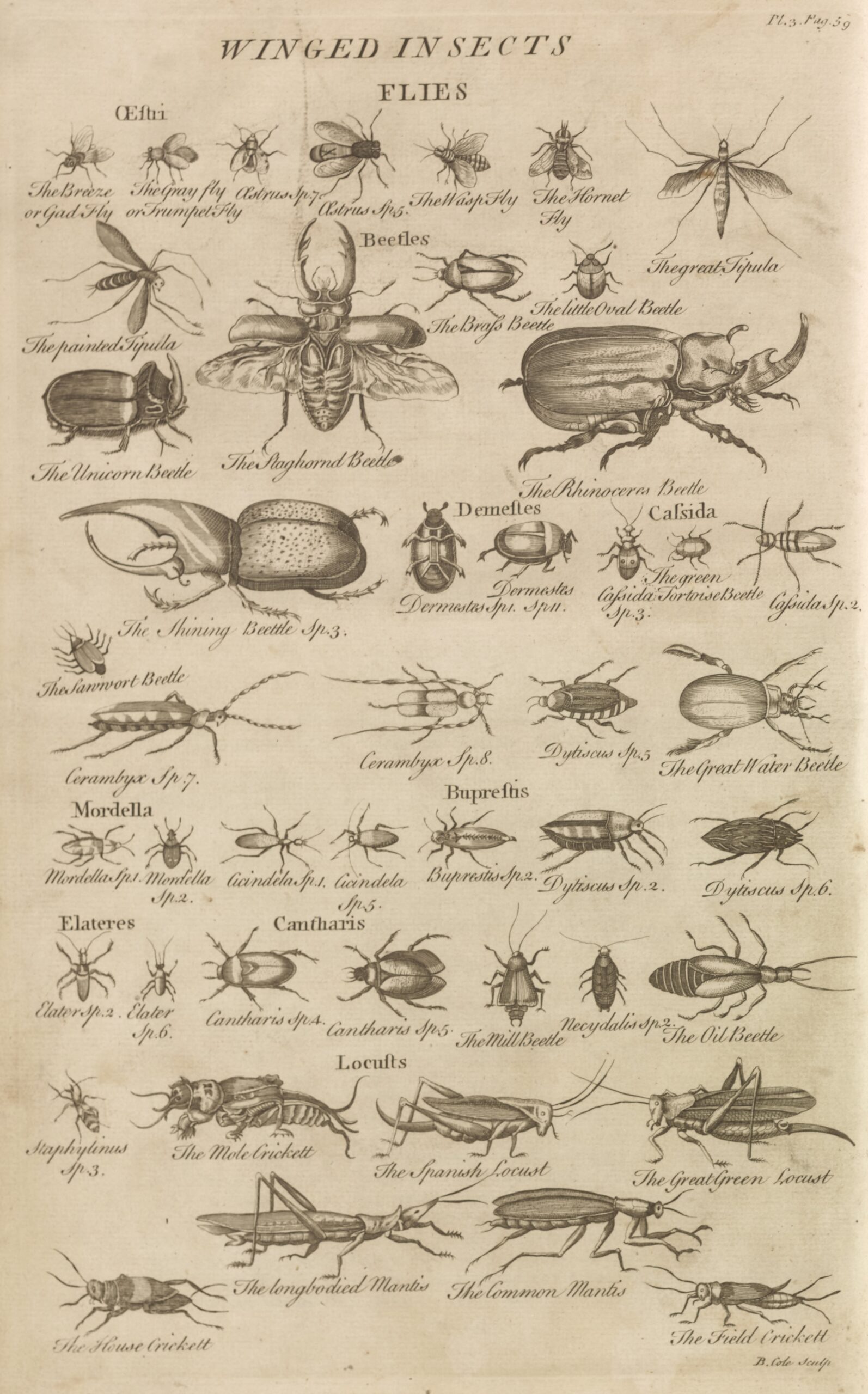

Same with An History of Animals, Containing Descriptions of the Birds, Beasts, Fishes, and Insects, of the Several Parts of the World (1752), another rare book featuring engravings of bugs and their microscopic body parts. Normally, looking at pictures of insects—even sketches and drawings—would completely gross me out. But instead, I’m zooming in as far as I can (just like a microscope!) to see the minuscule hairs on the tiny legs of the crickets, ants, beetles, and other critters that live in our digital collections.

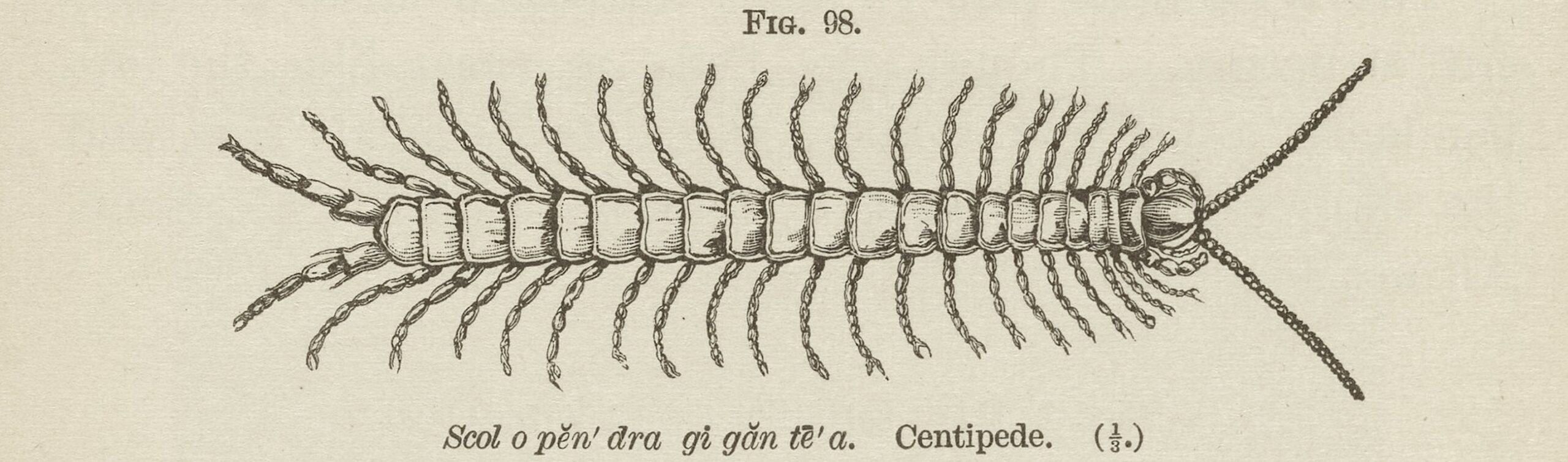

Then there’s Popular Zoology, one of a series of textbooks designed to help students better understand the animal worlds. This 1887 volume covers the vertebrates and invertebrates (which bugs are), with a chapter titled “Branch Arthropoda: Insects and Crustaceans” that features detailed illustrations and descriptive text.

According to the book, centipedes belong to the order Chilopoda (which I definitely should not have googled) and “are carnivorous forms, having the first pair of legs jaw-like, and provided with a poison apparatus resembling that of a spider. This poison is of use in killing insects and other small animals, and produces great pain and inflammation when inoculated in the human system.”

So they have hundreds of legs (yes, hundreds!) and they’re venomous? That sounds absolutely horrifying! And yet, I still want to (virtually) flip through all the pages, not only of Popular Zoology, but also these other rare books in our collections where even more creepy crawlies can be found:

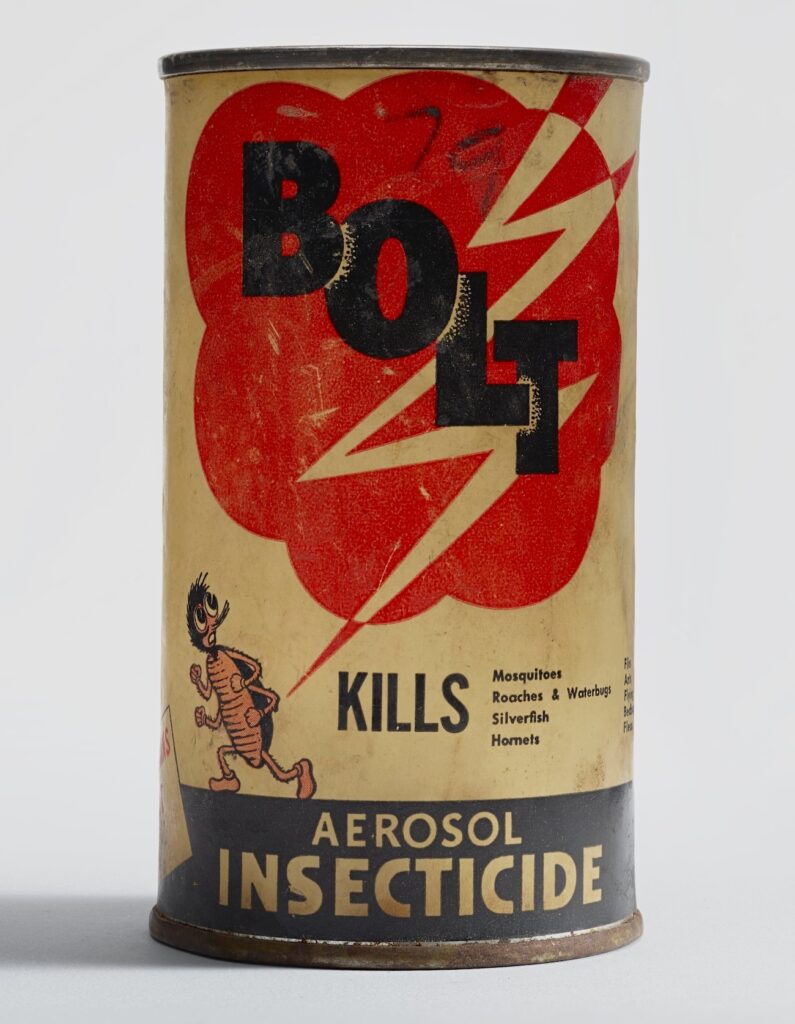

The Institute also has a large collection of vintage pesticide and insecticide cans, sprayers, and diffusers, as well as advertisements promoting DDT, toxaphene, thanite, and other products that kill bugs. “Bug killer” sure does have a nice ring to it, and I am fascinated by the (environmentally unfriendly) history of pest control. But I am also drawn to the bold graphics and cartoonish depictions of insects that should make me squeamish, but don’t.

Clockwise from top left: Sentenced to Death, Dow Chemical Company advertisement, 1938; Chase’s Products New Insect Bomb, 1927–1972; Just Press the Button…Bugs Drops Dead!, Black Flag advertisement, 1940–1945; and Bolt Aerosol Insecticide, 1950–1972.

A coworker captured that Philly “cock-a-roach” (WITH HIS BARE HANDS!) and placed it in a bag. I have no idea what he did with it (I don’t want to know!), but he told me you should never stomp on roaches since they might be pregnant and you could unintentionally disperse their eggs with your shoe. Like in your house.

Ewwwwwwwwww.

So, yes, I still hate bugs. Just the other day, during my dog’s post-dinner walk, I was attacked by a massive swarm of gnats or no-see-ums or some other teeny insect that caused me to flail my arms around, trying (and failing!) to swat them away. Picture Tom Hanks in that scene from The Money Pit where he’s in his yard, also being attacked by a swarm of bugs, right before discovering his “weak trees.” Only he wasn’t screaming, but I was. Just ask my neighbors.

Featured image: Microscopic view of an ant or pismire, from Micrographia: or, Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses, With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon, 1665.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.