Stories Untold

Why oral history is critical for the history of science and engineering.

Why oral history is critical for the history of science and engineering.

Judith Summers-Gates spent much of her scientific career as an analytical chemist working for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Department of Defense, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Her work focused primarily on testing the durability of textiles used in the military and the safety of color additives in food. She wrote papers and published reports, so we have a detailed documentary record of her contributions to the corpus of scientific knowledge.

None of those records, though, contain information about how Summers-Gates conducted herself as a scientist. They don’t say anything about her approach to problem solving, why she chose to perform one type of analysis instead of another, or how and why she may have modified a standard test to fit better with the chemical being analyzed. That pertinent decision-making is not something we find in the papers and reports scientists publish, yet it is fundamental to understanding the hows, whys, and whos of scientific knowledge production.

Like many of my friends, family members, and colleagues, I remember the experiments I performed with a home chemistry kit or in a school laboratory, and all the ways we introduced unintentional errors when mixing chemicals or titrating solutions, as well as the insights that led to getting excellent results. Science is not just about data produced, but is also about the people who produce that data: their choices, their histories, their worldviews, and their beliefs. So what can we do to enhance our understanding of Judith Summers-Gates’s work, to expand a trove of published papers devoid of any discernable traits that she brought to bear on her science?

We can ask her about it.

Oral history is a methodology that historians use to build upon and extend the documentary record, thereby providing a fuller and more vibrant history than can be achieved with published papers, news articles, and reports alone. Its practitioners date its origins in the United States to the early 20th century with the Federal Writers Project’s efforts to document histories of formerly enslaved people. This form of historical collection was, and still is, meant to give voice to the voiceless, to make sure the annals of history remember not just the political leaders, the military commanders, the business owners, and the Nobel laureates, but the plethora of people who actively participated in, witnessed, and contributed to history.

Speaking with participants in a controlled interview setting allows researchers to re-introduce the human component to history. The questions we ask in oral history interviews aim to expand our understanding of the ways in which people’s remembrances, their personhood, and their own experiences of the world around them contribute to our understanding of the past and how history unfolded.

Knowing more about a childhood spent fixing broken television sets; an education filled with dynamic, engaging, and supportive teachers; or the experiences of financial hardships can speak volumes to why people approach their lives and work in certain methodical ways, or how and why they chose, for example, to become teachers, activists, farmers, physicians, scientists, or engineers. Oral history interviews reveal the often overlooked personal contributions people make that have significant impacts on the course of history.

Conducting and sharing oral history interviews also allows us to learn about people whose stories are not otherwise documented. For example, while Shuko Tamao, our curatorial fellow, was writing a history dissertation about how people with disabilities lived with the threat of being institutionalized in the post-World War II United States, she became frustrated that many archives lacked records from the perspective of those with disabilities: most of the records available were created by doctors to explain why their patients needed to be committed to institutions like state hospitals or state schools, where many would live without any promise they could leave.

Shuko wanted to address this imbalance within the documentary record and found that oral history was the best tool to create a richer, more detailed history that included the voices of those institutionalized, not just the doctors who committed them. She launched an oral history project to gather the stories, remembrances, and perspectives of ex-patients, detailing their experiences and providing a much more introspective and nuanced history of institutionalization from the viewpoint of those committed to these facilities.

Oral history can also serve as a form of testimony or witnessing. In Sarah Schneider’s past work utilizing Holocaust testimonies, she saw how oral histories amplified the voices of people who had been persecuted and allowed them to share how the events of the Holocaust and World War II impacted them. Such testimonies have been used to determine who perished and who survived, providing invaluable information for family and friends, and in some cases, allowing loved ones to reconnect.

Testimonies have also been used to corroborate details about specific people, places, and events during the Holocaust. Oral histories give voice to those being interviewed and make their experiences known to family and friends, the general public, and generations of researchers to come. Instead of being labeled as voiceless “victims,” interviewees are able to share their important perspectives as “survivors,” enriching their own lives and the historical record as well.

In a similar vein, through oral history interviews we can learn about often overlooked scientists who do so much to further our knowledge and understanding of the natural world but who do not receive public recognition, awards, or honors. Interviewing these professionals allows us to understand the role of science in our everyday lives; the work that goes into furthering scientific knowledge; and the complexities of navigating this profession within academic, industrial, and governmental infrastructures.

Oral histories of scientists allow us to learn more about the hidden side of research—how individual social, cultural, political, and/or religious beliefs have guided scientists down the paths they chose and the reasoning behind such decisions; details about which experiments failed and what accidents led to success; and the rationale behind their scientific pursuits. Moreover, oral history interviews highlight the lived experiences of these scientists and the ways in which their personal lives play important roles in their scientific careers—for example, as women ostracized for their gender; as immigrants navigating unfamiliar and sometimes confusing cultural structures; or as people with disabilities working within physical and social structures not designed for them.

In the Science History Institute’s oral history interview with Judith Summers-Gates, she shares that her retinopathy of prematurity—low vision caused by excessive oxygen in her incubator soon after she was born prematurely—led to her seeing the world in vastly different ways than her colleagues. Summers-Gates recalls how the world treated her differently because of her limited vision.

As a young Girl Scout, she went on a trip that included birdwatching. Her Scout leader assumed that Summers-Gates’s low vision would prevent her from traipsing through the forest with her fellow Scouts, so a table was set up for her to do an art project while everyone else went on a hike. Knowing in advance that this would likely happen and unbeknownst to her Scout leader, Summers-Gates stowed a large bag of birdseed in her pack before the trip. After her fellow Scouts and the Scout leader left for the hike, she spread the birdseed in an open clearing and soon welcomed all the birds she was supposed to find while hiking in the forest. Her troop returned sometime thereafter, discouraged by the paucity of birds in the forest to find that Summers-Gates had seemingly brought all the birds to her.

Like the troop leader, people made assumptions about Judith’s capabilities throughout her scientific career because of her low vision. However, that low vision helped Summers-Gates see the world in vastly different ways, and many of her colleagues came to appreciate her vision of the world around her. And that perspective is one that was never captured in the articles and reports that Summers-Gates wrote about her scientific findings. Yet, it’s a perspective crucial to understanding her science.

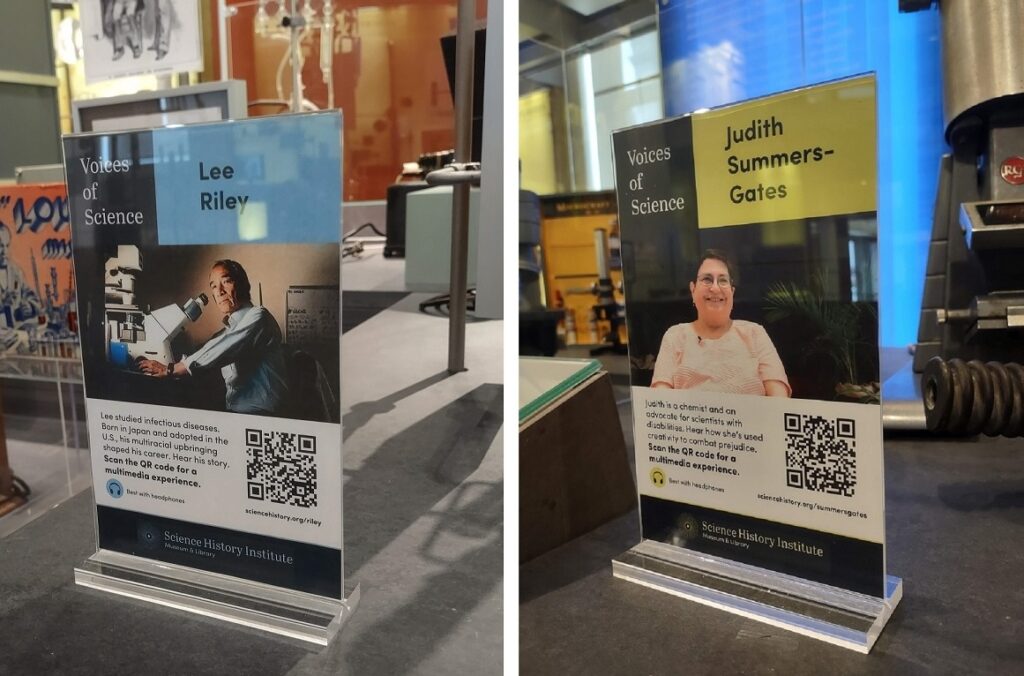

If you’d like to learn more about Judith Summers-Gates and other scientists through their own words, please visit our museum, where we recently launched our Voices of Science oral history project. Voices of Science connects objects on display with the humans who created and used those objects through QR codes that visitors can scan to access multimedia videos with oral history interview highlights and archival images.

How to read a book when the pages are out of order.

An Institute fellow sheds light on an enigmatic trio.

We’re still scratching our heads over how the brain works.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.