Stomping the Margarine

Life when we had to color our food.

Life when we had to color our food.

Today margarine is a common grocery item, and many people prefer it to butter. However, it took time for margarine to gain a following in the United States, especially since it originally required more work in the kitchen than simply removing it from the refrigerator.

When margarine first came to the U.S. in the 1870s, the butter substitute intrigued everyone—everyone except dairy farmers who worried about the impact it could have on their industry. They successfully lobbied Congress to pass a tax that made margarine more expensive than butter, and on August 2, 1886, President Grover Cleveland signed the Oleomargarine Act into law.

Although margarine was taxed at two cents per pound (60 cents today), manufacturers continued to produce it—and they started coloring it yellow to resemble butter. By transforming its unappetizing white into a pleasing yellow, manufacturers saw sales of margarine increase.

Some people, particularly dairy farmers, still feared margarine’s rise in popularity and began lobbying individual states to address the margarine issue as well. By 1898, 32 out of the then 45 states had passed laws restricting the artificial coloration of margarine. States such as Minnesota even required margarine to be colored pink to clearly indicate it was artificial and not real butter. In 1898, however, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down these “pink laws” as unconstitutional.

In light of this defeat, the dairy industry decided to pursue another path to limit the color manufacturers could dye margarine and again lobbied Congress. In 1902 they obtained an amendment to the 1886 Oleomargarine Act. This new amendment taxed colored margarine at 10 cents per pound ($3.36 today) and white margarine at a fourth of a cent per pound (8 cents today).

Although colored margarine seemed doomed by this higher tax, manufacturers quickly crafted a creative workaround. They began including a capsule of yellow dye with each pound of margarine so consumers could color it themselves. Soon coloring margarine became a commonplace kitchen task that persisted well into the mid-20th century. You may even have relatives who remember doing this.

As newspaper stories and online comments reveal, some kids loved to participate in the chore. Maxine Clark remembers running into the kitchen with her brother just as her mother started to color margarine, asking, “May I stomp the butter? May I stomp the butter?” (The “butter stomper” was a special tool, not a pair of feet!) She watched in fascination as the margarine changed from white to yellow, carefully turning it several times to make sure the food coloring was entirely mixed in.

Not all folks had a “butter stomper” like Maxine’s family. Milton Sernett recalls mixing the yellow packet with a wooden spatula or, if his mother wasn’t present, with his fingers. Rob Howell, for his part, didn’t love the task, although it only took about 10 minutes. Once softened from mixing, the margarine was still unappealing but slightly improved over its natural state. “It was always pretty unappetizing, but it was super unappetizing when it was white,” he says.

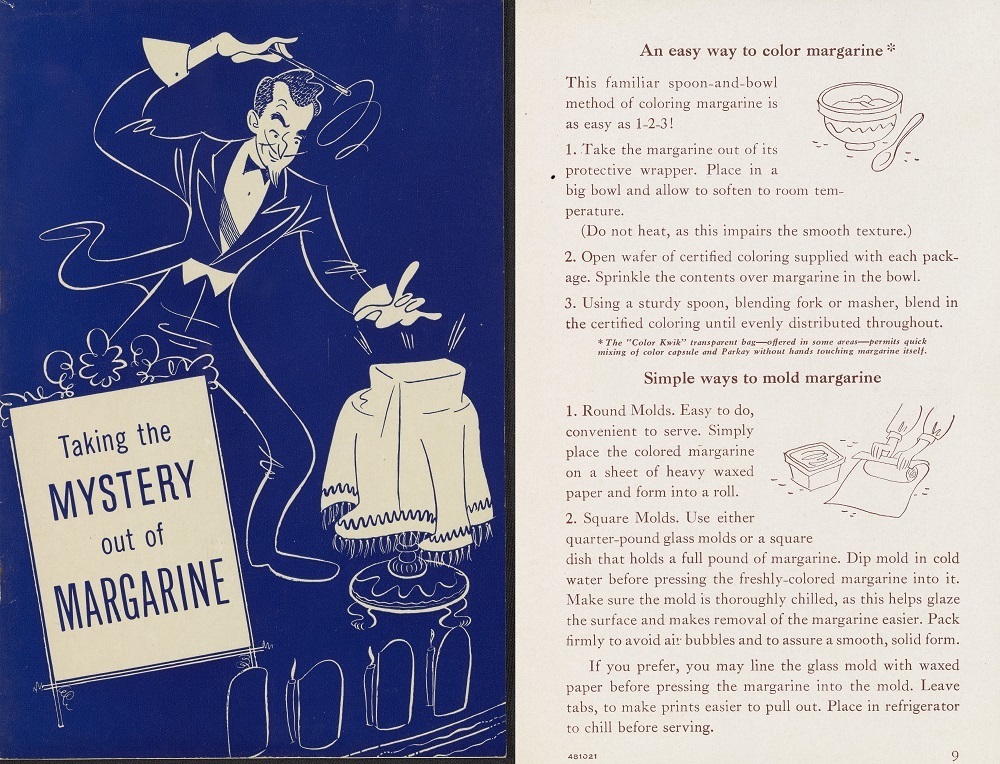

Cover and page 9 from Taking the MYSTERY Out of MARGARINE, informational pamphlet created by Kraft Foods Company, 1947.

To combat the unease of consumers like Howell and encourage them to jump on the margarine bandwagon, manufacturers produced advertisements, promotional materials, and pamphlets like Taking the MYSTERY out of MARGARINE. This pamphlet, which can be found in the Institute’s collections, devoted eight entire pages to convincing consumers that margarine’s ingredients were natural, familiar, and nutritional. It also provided step-by-step directions for coloring and molding margarine into a yellow semblance of butter.

For those lucky enough to have “Color Kwik” transparent bags (mentioned above in small italics under the three easy steps to color margarine), yellow margarine could be achieved in less than 90 seconds according to this Parkay ad from 1948.

Advertisement for Parkay “oleomargarine” with Color-Kwik technology, from the April 16, 1948, issue of the Boston Daily Globe.

Other advertisements such as “The Smoothest Spread to Put on Bread,” also from the Institute’s collections, used the bright yellow color that one associates with butter to subtly suggest that margarine was just as good as butter—and cheaper.

Detail of “The Smoothest Spread to Put on Bread,” advertisement from the National Association of Margarine Manufacturers, 1948.

Margarine did eventually catch on and became widely accepted, especially when dairy was rationed during World War II and the years following. Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt even participated in a commercial for Good Luck margarine in 1959.

While many people started using margarine in lieu of butter, not all were willing to make the switch. In the Institute’s oral history interview with Hubert N. Alyea, the chemistry professor recalls that LeRoy McCay, under whom he studied at Princeton, discovered an easy way to determine whether a spread was butter or margarine: leave it out on crackers for the mice. The rodents would eat crackers smeared with butter, but they wouldn’t touch the margarine-slathered crackers.

In 1950 the federal government ended its taxes on margarine, as the butter substitute’s rise in popularity meant it no longer made sense to tax it. At last, consumers could finally purchase colored margarine in the grocery stores of most states—except Wisconsin, which is known for its dairy industry. Until 1967 when Wisconsin finally removed its ban, consumers had to smuggle colored margarine blocks from neighboring states.

To learn more about this surprising food battle, you can listen to a Distillations podcast that digs into the strange history behind the fight between butter and margarine.

Featured image: Detail of Now! Homogenized for Better Flavor!, advertisement for Durkee’s margarine, 1955. Science History Institute.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.