Scientists, Engineers, and the End of the Vietnam War

On the big politics of the Small Business Innovation Research Program.

On the big politics of the Small Business Innovation Research Program.

“Small business” is a term that frequently comes up in political speeches from members of both major parties in the United States. Where did this term come from and why are politicians so focused on something that sounds so dull? The Small Business Innovation Research Program Records offer a window into the political transformations that vaulted small businesses to the top of the (at least rhetorical) political agenda from the 1970s and 1980s through today

Dr. Arthur Obermayer, the subject of the Research Program Records in the Institute’s archives, founded and ran the Moleculon Research Corporation—a chemical, polymer and pharmaceutical research and development company. He later founded an early-stage venture capital firm and acted as an “angel investor.” He was an influential activist within the Democratic Party, especially regarding science and technology policy, but also in the context of economic policy. (He is also known for litigating the ownership of the rights to the Rubik’s Cube.)

Obermayer also spent most of his life in the town where I was born: Newton, Massachusetts. I asked my mother, who is presently a city councilor in this town, whether she knew any older folks who had ever heard of him. I heard back quickly that just as he was very active in the state and national Democratic parties, he was also involved in the local Democratic party. I plan to interview these local politics figures who knew him as a part of my research following this blog post.

Operating at the other end of the political spectrum, Arthur’s father Leon was a staunch Republican. Leon was also a former civil attorney and a member of Philadelphia Board of Public Education; in fact, in the 1950s, Leon wanted to fire any Philadelphia teachers who invoked their First or Fifth amendment rights before the House Un-American Activities Committee’s anti-Communist investigations. He was, however, more liberal on issues of racial justice and disability rights issues. He likewise helped Arthur with some of his political aims.

For example, he wrangled Republican Senator Scott of Pennsylvania on legislation Arthur supported on economic conversion from the Vietnam War; that is, adapting the economy from a war economy to a civilian economy in anticipation of the end of the Vietnam War. Since the U.S. never demilitarized after the Korean War, winding down military spending and organization after the Vietnam War was a big task. And this economic conversion left many engineers and scientists, who had previously relied on government contracts, unemployed.

Through his subsequent advocacy and political activism, Arthur Obermayer played a large role in remaking U.S. infrastructure around science and technology. He organized other scientists and engineers around a political program to stabilize their labor and funding; he sold this to the national security state as a way to maintain support for a crucial workforce of the “Cold War triple helix” of defense, industry and academia.

By working with Massachusetts Democratic senators Ted Kennedy and John Kerry through the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, he helped bind the Democratic Party to the interests of the emerging tech sector—made up then of small science- and engineering-focused government contractors—in a political alliance that has only recently begun to fray. The problem Obermayer was trying to solve, in Kennedy’s words, was that “science has no real constituency.” As Obermayer put it in at a 1971 National Engineer’s Week Seminar on Employment Conversion in Boston:

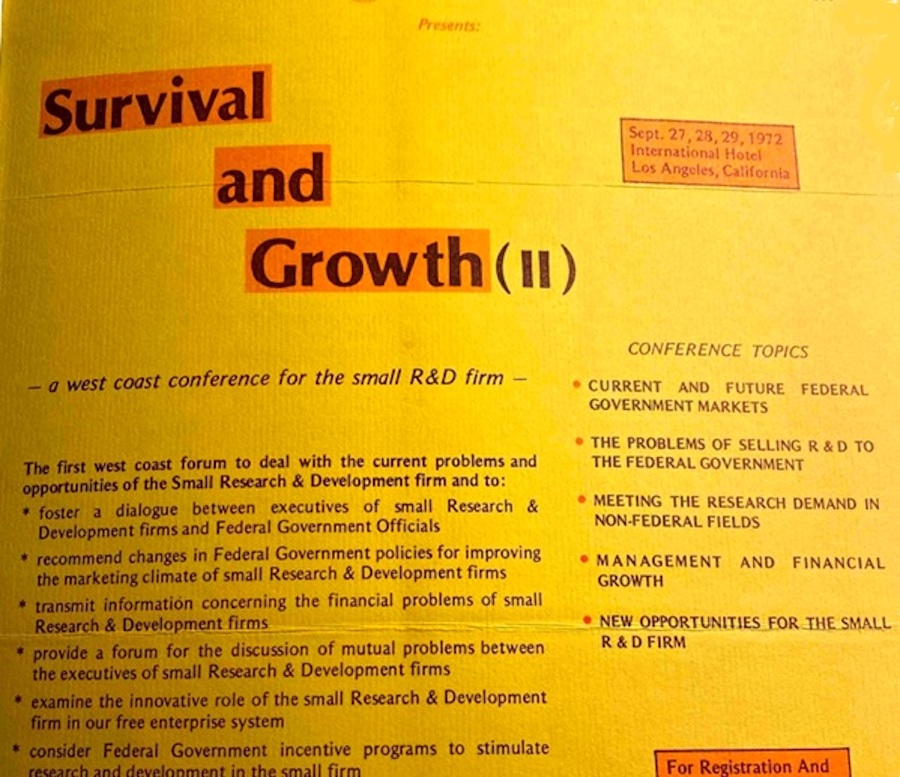

To solve this problem, Obermayer helped organize and attended several conferences on the subject of unemployed technicians, engineers, and scientists, such as the one below sponsored by the Small Business Association, the U.S. Department of Commerce, and NASA.

In the wake of Vietnam, concern about unemployment and loss of status among engineers and scientists led figures like Obermayer to organize this group into a political bloc. By the 1980s, this organizing turned into advocacy for “small businesses” as a political constituency. By small businesses, these figures typically meant what we today would term “high-tech start-ups.” These “small businesses” saw venture capital as an alternate funding source that avoided the problems of relying on the government for contracts (especially with the stigma they endured because of backlash to the Vietnam War fresh on their minds).

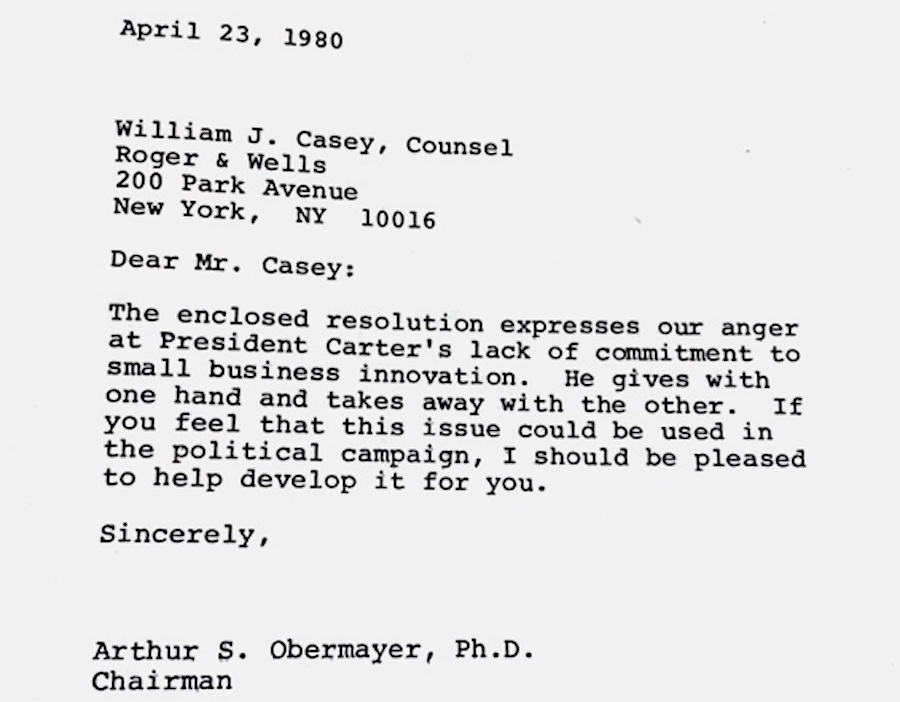

Likewise, figures in conservative economics such as William J. Casey (of Iran Contra fame) saw the potential relationship between these “small businesses” and venture capital as a vehicle for remaking government and the economic environment: pushing tax cuts (for example, removing or lowering the capital gains tax, estate tax, as well as corporate taxes for “small businesses”), slashing regulations, shrinking government, reversing anti-monopoly legislation, and lowering minimum wages.

Figures such as Obermayer didn’t just want tax cuts and reductions in certain kinds of government intervention—they also wanted more help from the government (from the Small Business Administration, for example) under Carter. Obermayer was so committed to this cause that despite being a Democratic operative and ally, he offered criticism of Carter’s handling of his group’s priorities that was used by Reagan’s campaign manager (the same William J. Casey) during the 1980 presidential election.

Arthur Obermayer is one of several figures who remade the Democratic coalition from working-class, often unionized whites to suburban professionals by mobilizing scientists and engineers in the wake of Vietnam. This is also the beginning a period where science and technology played a more central role in politics; Obermayer helped inaugurate this development by organizing scientists and engineers into an important voting and lobbying bloc. Specifically, Oberymayer and others helped shape the alliance between subsequent generations of Democrats and what would later be termed the “tech industry.”

The success of the coalition he built with figures like Casey around proto-startups—a crucial piece of the emerging “tech” industry—can be measured by the fact that many of the measures these small business groups advocated became law in the next few decades.

Featured image: Front page of the 1969 Roster of the Engineering Manpower Commission of the Engineer’s Join Council. The three pillars likely represent what is sometimes called the “Cold War triple helix” of defense, industry and academia.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.