Robert Boyle in Signature D

How to read a book when the pages are out of order.

How to read a book when the pages are out of order.

Descriptive bibliography is considerably more complicated than you might think. The bibliographies you compiled in high school or college were lists of books, usually giving their authors, titles, and publishing information. Descriptive bibliography, on the other hand, not only enumerates the works by a particular author or on a particular topic, it also offers an exhaustive account of the physical characteristics of each book to provide as much information as possible on the printing of each work. Considering that most of the information at the disposal of descriptive bibliographers comes just from the physical book in front of them, their conclusions sometimes have the air of godlike omniscience.

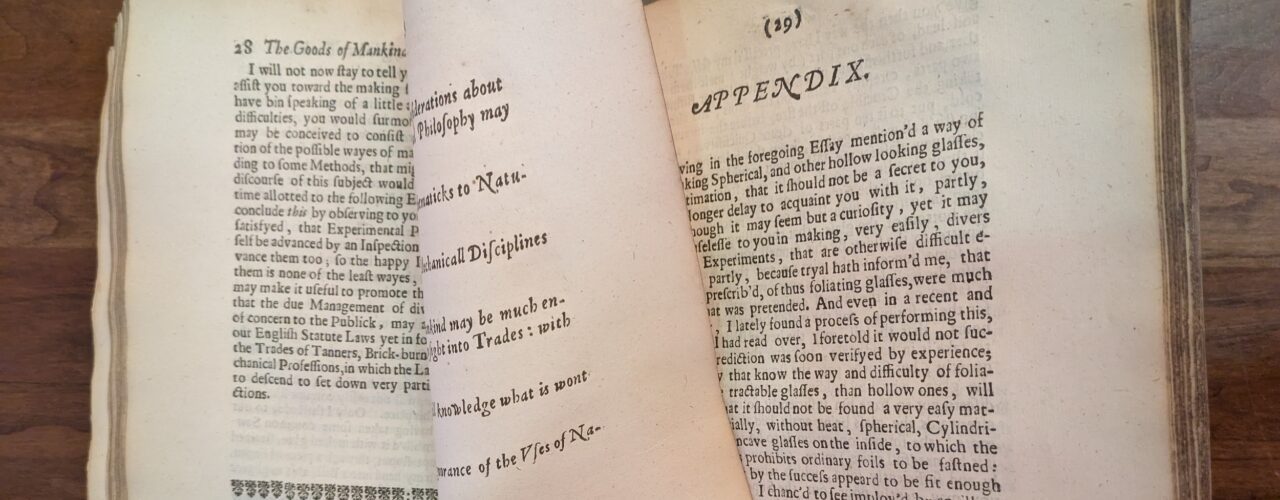

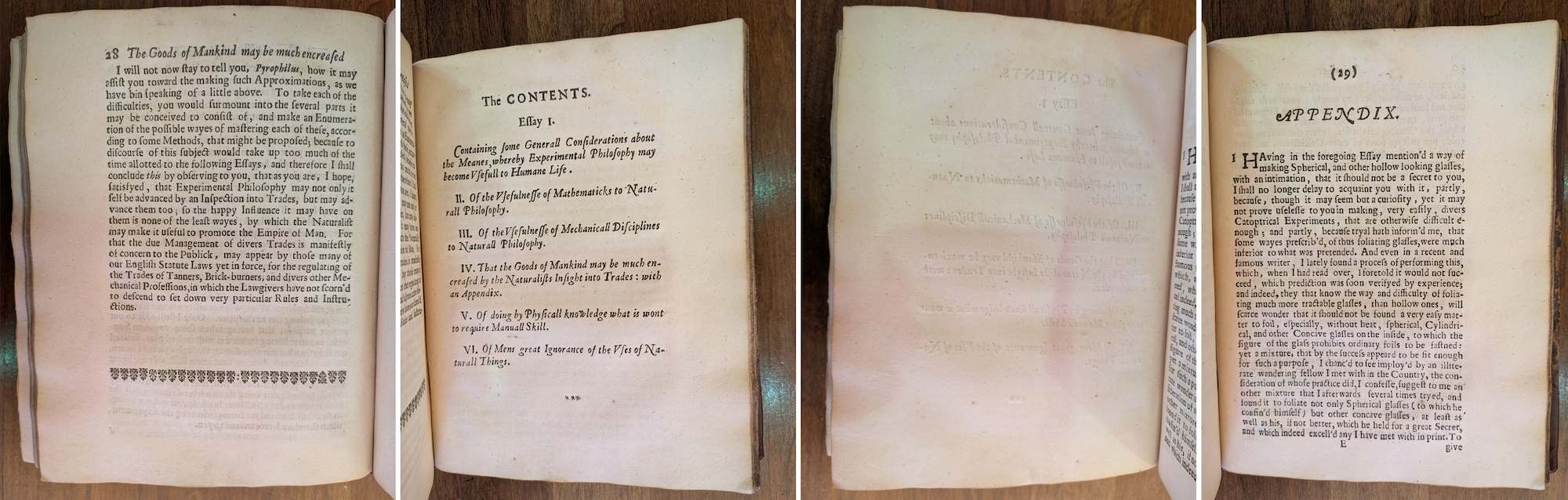

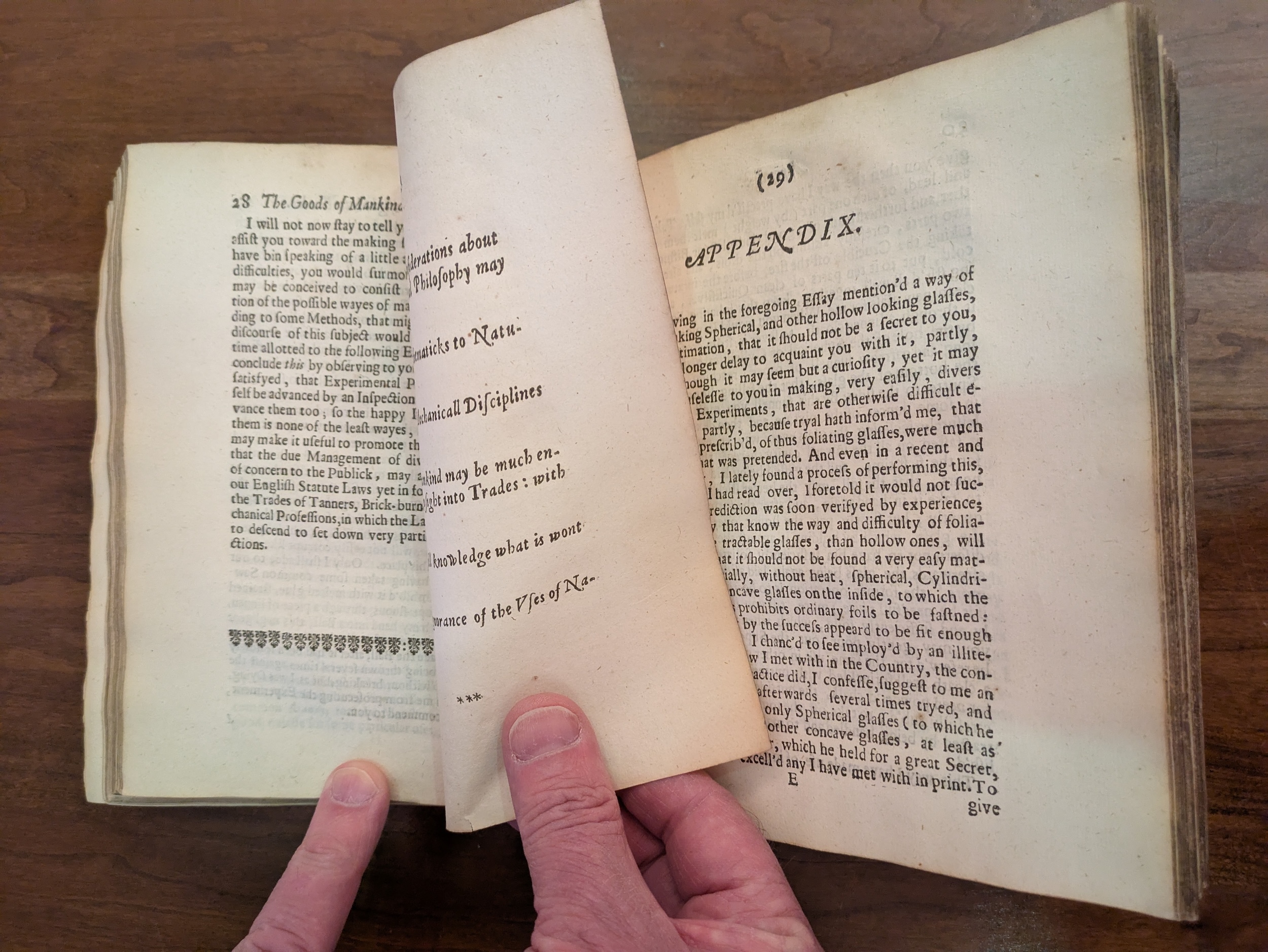

Consider the following from John Fulton’s magisterial A Bibliography of the Honourable Robert Boyle (2nd edition, 1961). In describing Boyle’s Some Considerations Touching the Usefulnesse of Experimental Naturall Philosophy, volume 2 (1671), Fulton writes, “the [t]able of contents (***) . . . was really printed as leaf D4.” Fulton is saying that when the printer reached the end of one section of the book, he used the leftover blank page at the end of the D signature—which would have been the front page of leaf D4—to print the table of contents, which he marked, or “signed,” with three asterisks (***) at the bottom to indicate that it was to follow signature ** at the end of the book’s front matter.

To understand this better, it will help to know how books were typically printed in the handpress period. First, some terminology: a leaf refers to the whole page, front and back, whereas a page refers to just one side. Usually, the odd-numbered pages are on the front of the leaf and the even-numbered pages on the back. The printing process usually began with the start of a work’s main text on page 1, and the front matter (that is, the title page, dedication, table of contents, and other material outside the book’s main text) were printed last.

Several reasons likely drove this practice. Since printers didn’t own enough type to set up an entire book at once, they typeset and printed on a rolling basis. So, for instance, they wouldn’t know where the main text sections fell to be able to provide their page numbers for the table of contents until the entire main text was printed. This sequence of printing, incidentally, is why to this day the front matter of a book is numbered with Roman numerals while the numbering of the text starts with Arabic numerals on page 1, even though the technology of printing is entirely different today. Go ahead: grab a book off the shelf and take a look.

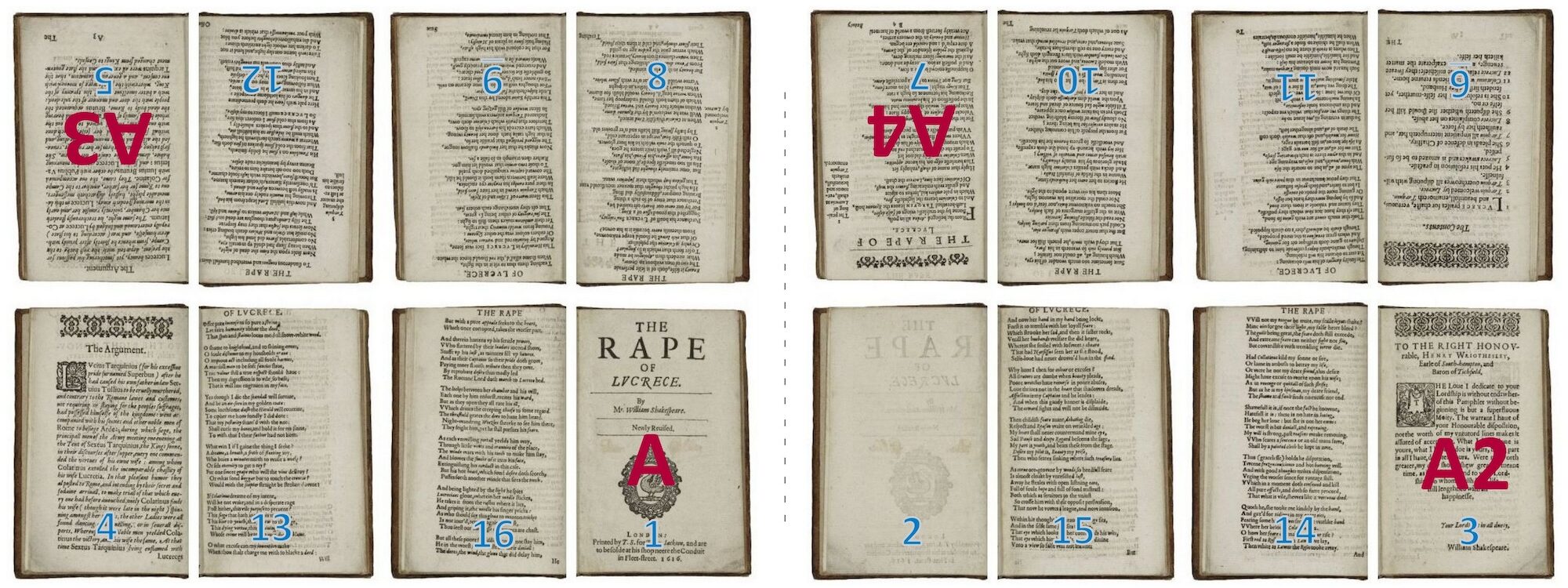

Second, the unit of printing for the printer wasn’t the page: it was the sheet. Depending on the format of the book, 4 or 8 or 16 (or more) pages of a book were printed onto the front and back of a single sheet of paper. After printing, this sheet would be folded in half several times until each leaf had one page on the front and back. These sheets were “signed,” which means the printer designated them with a letter of the alphabet (A, B, C, and so on), or sometimes a symbol, printed at the bottom of the leaves.

The printer would usually only sign a subset of the leaves on a sheet: always the first, and then typically the following one to three, so that whoever was folding the sheet could check the order of the leaves. But once they had made the requisite number of folds, as long as the first few leaves were in order, the remainder were necessarily so, and those leaves were not signed. The leaves in each signature are designated by their order in the signature, so D4 mentioned above was the fourth and last leaf in signature D.

Once the sheets were printed, the printer’s job was finished, and the stack of printed sheets would go the binder. The binder would fold each sheet in the appropriate number of times so that a single page was on each side of each leaf; they would then bind together all “signatures” (which is the name for all the leaves from a single lettered sheet), using the signature marks A, B, C, and so on, to put them in the correct sequence. Often, they would trim the edges of the text block, leaving no evidence of the folds or signatures except the printer’s letters at the bottom of the front of the leaves denoting the signature.

As the printer got to the end of a work, it was not uncommon to print some of the front matter on blank leaves left on the last sheet of the main text so as not to waste paper. In the example above, Fulton is saying that after the text finished on D3, there was one blank leaf left on the sheet, so the printer printed the single page table of contents on D4. But he signed that page *** (not D4) to indicate that it was to follow the preamble at the front of the book that was printed on eight leaves in two signatures signed * and **. (Often the front matter of books was signed with non-alphabetic pieces of type, since the main text usually began with signature A).

But if the page signed *** was meant to be detached from signature D and moved to the front of the book, how would Fulton ever know where it came from? How could he say with such certainty how the printer had set up signature D? Here it might be useful to touch on something descriptive bibliographers call the “ideal copy.” The ideal copy of a book is the order of the leaves if they were put together as intended. It is a curious concept: how are we supposed to know what was intended? In this case the printer’s intention is clear. By signing the table of contents ***, he was telegraphing well that it was intended to follow * and **.

And now we come to the Othmer Library’s copy of Some Considerations Touching the Usefulnesse of Experimental Naturall Philosophy, volume 2, for it is not an ideal copy. In the case of our copy, the binder made a mistake. He took signature D, folded it up as usual (remember what I said about the pages necessarily following in order if the first folds were correct?), and carelessly bound the table of contents in as the last leaf of signature D, rather than removing it to the front of the book. And it is from “un-ideal” copies such as ours that descriptive bibliographers like Fulton can infer how the sheets were set up, even if in the ideal copy individual leaves in a signature were meant to be cut and moved to other parts of the book. Copies like ours are clinching evidence that *** was printed as part of signature D. If we disbound our copy it would show that D1 and *** are conjugate—that is to say attached, on the same piece of paper with the fold now concealed within the binding of the book.

It is interesting that our binder may have been lulled into inattentiveness by the existence of a signature E. If you are folding and stacking signatures A, B, C, D, and E, why would you carefully examine the end of signature D to see if any front matter were lurking there?

What is on signature E is an appendix on making spherical and other hollow-looking glasses, which we can infer Boyle only added to the book late in the printing process. Evidence for this inference emerged from my work with the Chymistry of Isaac Newton project, a major focus of which is determining when Newton wrote his various alchemical manuscripts. Part of this effort involves a comprehensive analysis of the printed sources Newton cites in his manuscripts, which includes Boyle’s Some Considerations Touching the Usefulnesse of Experimental Naturall Philosophy, volume 2.

For example, if Newton cites this work, we can be sure that the manuscript dates from 1671 or later. Interestingly, Alex Wingate, a graduate student working on the project’s definitive bibliography, has found that the four pages of signature E are missing from both (or perhaps all) the copies of Boyle’s book that are digitized and available online. This fact, and the mishap with our signature D, strongly suggest that this appendix was added only at the very end of printing and that some copies left the publisher without it. Indeed, why would the printer print the appendix on a separate signature (E) if space were available when he was printing signature D and he could simply begin the appendix on the blank D4?

The pagination of the appendix does not betray its last-minute addition. It follows continuously from the end of the text on D3 and the pagination of the next section begins over at 1. As a matter of fact, all six essays in the book are separately signed and paginated, each beginning over again with signature A and page 1. The table of contents on ***, which was printed at the end of the fourth essay, is the only way to know how they were meant to be ordered. But that is another peculiarity and a story for another time.

An Institute fellow sheds light on an enigmatic trio.

We’re still scratching our heads over how the brain works.

Highlighting the journeys and contributions of scientists who immigrated to the United States in the 20th century.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.