Money Talks

Applying numismatics to environmental board games.

Applying numismatics to environmental board games.

We’ve all used fake money when playing board games. Players hide fake money in socks, tuck it under the game board, or stuff it under their shirts when nobody is looking. More honest players deal money meticulously, carefully count their own, and keep a close eye on their compatriots. For most board game players, the fake money in a game is banal. It is a tool to advance gameplay. Few likely pay attention to the actual drawings and images on the games.

But board game currency can be rich cultural artifacts. Just like the designers of authentic currency, game designers summon a deep well of cultural references to design the money of games. Though fake, these bills can use complex iconography and influences.

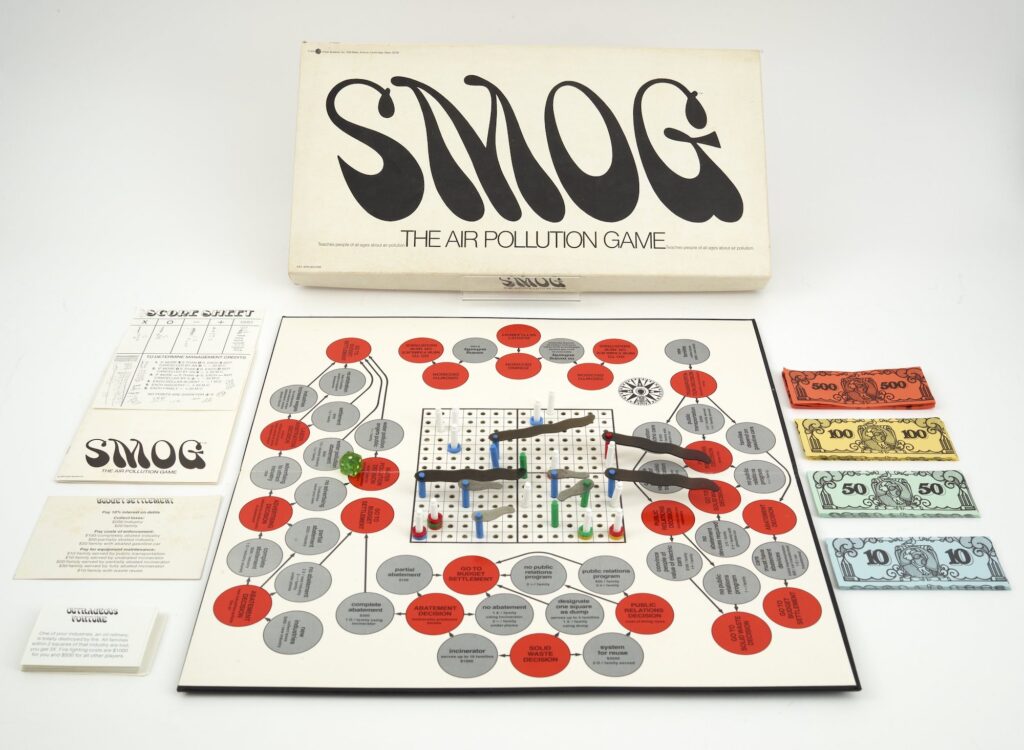

Here at the Science History Institute, we have recently been acquiring board games with environmental themes. Some of the games from the 1970s have been curated in an outdoor exhibition—Playing Dirty—that is on view on the façade of our building in Philadelphia through October 2023. Studying the currency of games in the broader collections can help us begin to understand the environmental issues important to board game designers and the nuanced ways in which money functioned as a hypothetical solution to environmental challenges.

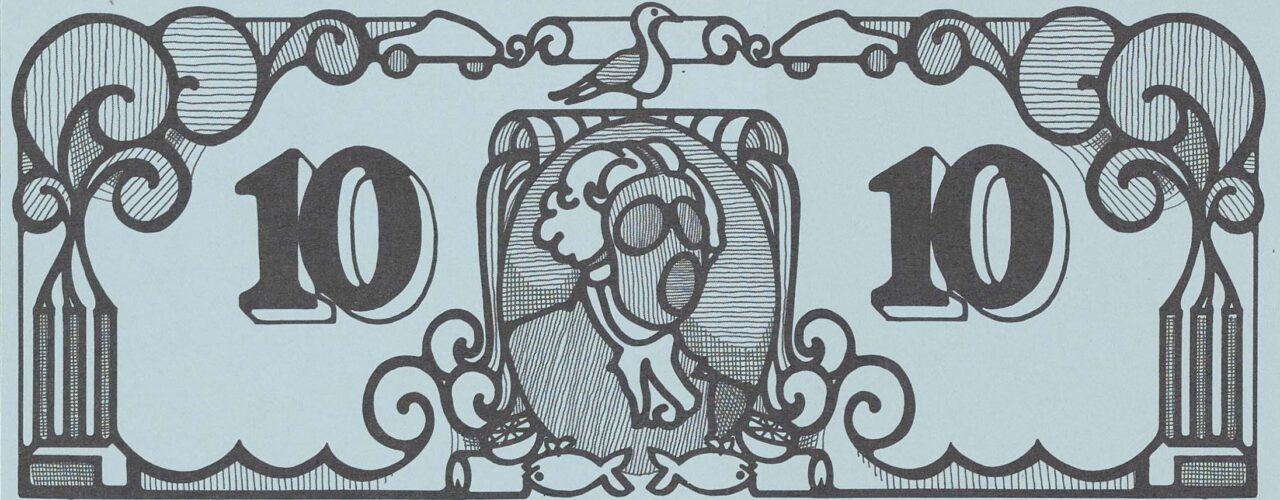

In Smog, players collect money through taxes and can spend it on programs to control pollution and collect management points. The game’s currency contains the most complex iconography of the group. The central image is George Washington wearing a gas mask to protect against air pollution.

Gas masks have been a popular prop for anti-smog activists since the 1950s. In 1954 activists in Los Angeles wore masks in protest against government inaction on air pollution. Gas masks have remained powerful symbols of protest since then.

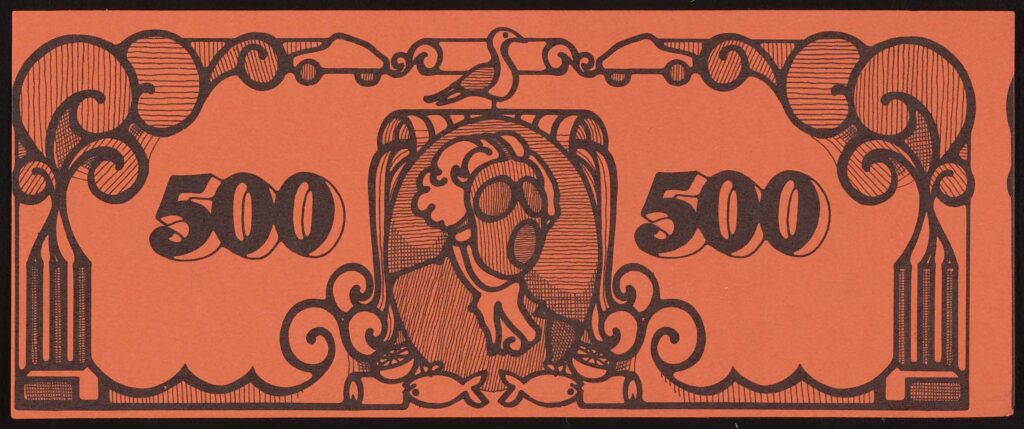

Working clockwise from the bottom right corner of Smog’s $500 bill pictured below, we first encounter smokestacks spewing smoke into the air. Air pollutants were the focus of the Clean Air Act of 1970, which targeted air quality. At the time, many U.S. cities experienced smog days so toxic that the air turned deadly. In 1966, particularly intense smog killed 200 people in New York City.

The smoke billowing from the stacks leads our eyes to cars. Connecting the two cars is a catalytic converter: a technological solution for car pollution that converts the carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxide of car engine exhaust into water and carbon dioxide through a chemical reaction. In 1975 Congress began mandating catalytic converters on new cars built in the United States.

The next series of images in the bill’s center highlight the problem of solid waste. A seagull is perched in front of the catalytic converter. As scavenger birds, seagulls have adapted to humans and garbage by scavenging at solid waste dumps. Lemons, cans, and dead fish along the image’s bottom edge represent the problems of solid waste disposal. In the 1970s open waste dumps and the incineration of solid waste were popular methods for communities to dispose of their waste. In Philadelphia, for example, the East Central Incinerator opened in 1966 next to the Delaware River. It used one million gallons of water every day to minimize air polluting fly ash.

Taken together, the iconography on Smog’s currency reflects the interconnected problems of industrial air pollution, solid waste, and vehicular emissions. Though the portrait of George Washington in a gas mask captures the viewer’s attention, the supporting images are just as important for explaining why the first president of the United States needed a mask at all.

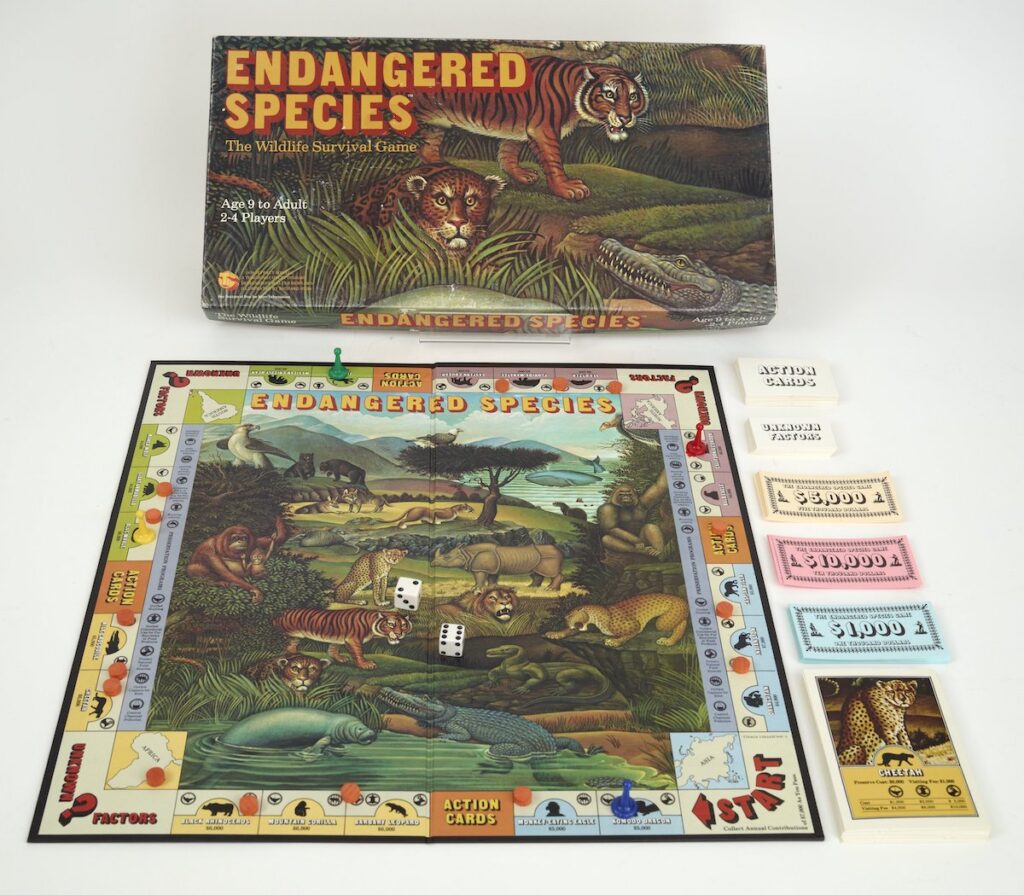

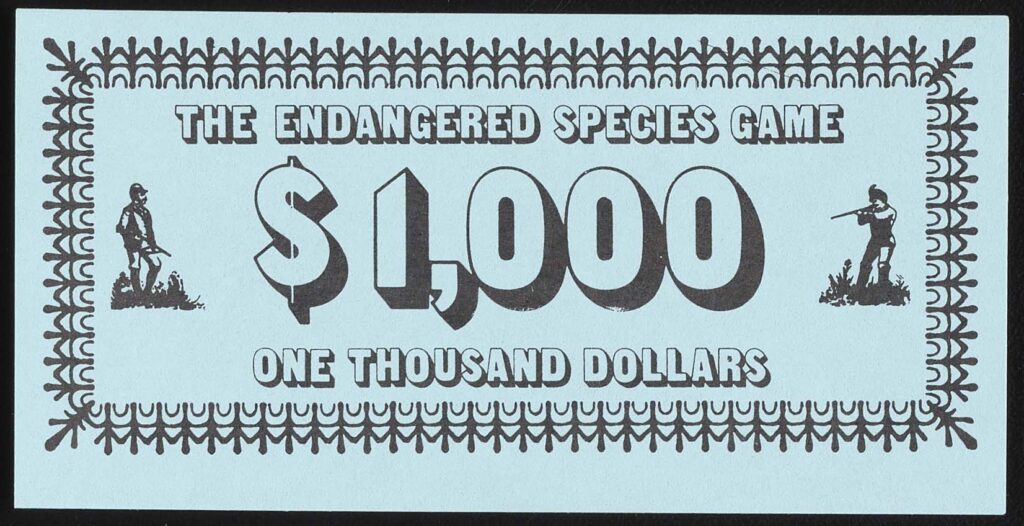

In the Endangered Species game, players win by creating animal preserves for threatened species under threat. Game money is used to buy preserves and set up species protection programs. Other players pay visiting fees when they land in those spaces. But the iconography on the game money suggests darker undertones to the game.

The bill’s border is an ornate fleur-de-lis motif reminiscent of the fencing around royal sites such as Buckingham Palace or the Palace of Versailles. On the game currency, the fencing motif might suggest that building and maintaining preserves to prevent species loss is the work of the economically and politically powerful.

Two figures on the currency carry rifles. Their silhouettes evoke white Victorian self-styled hunters and explorers in Africa. Men such as Henry Morton Stanley popularized the garb, with the distinctive pith helmet borrowed from colonial armies.

This raises important questions about the motivations of the board game itself. What does the use of the white safari hunter iconography reveal? It may have reflected concerns that creating animal preserves in the late 20th century would simply become modern versions of Victorian hunting preserves, where the species were preserved for only a few elites.

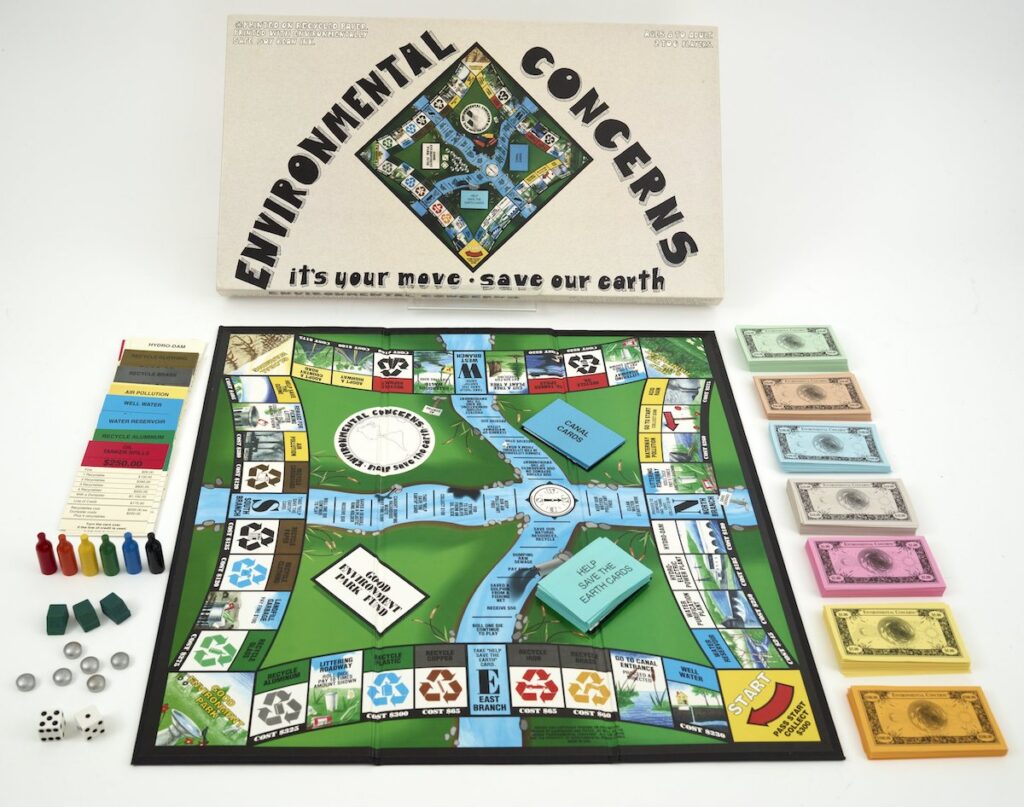

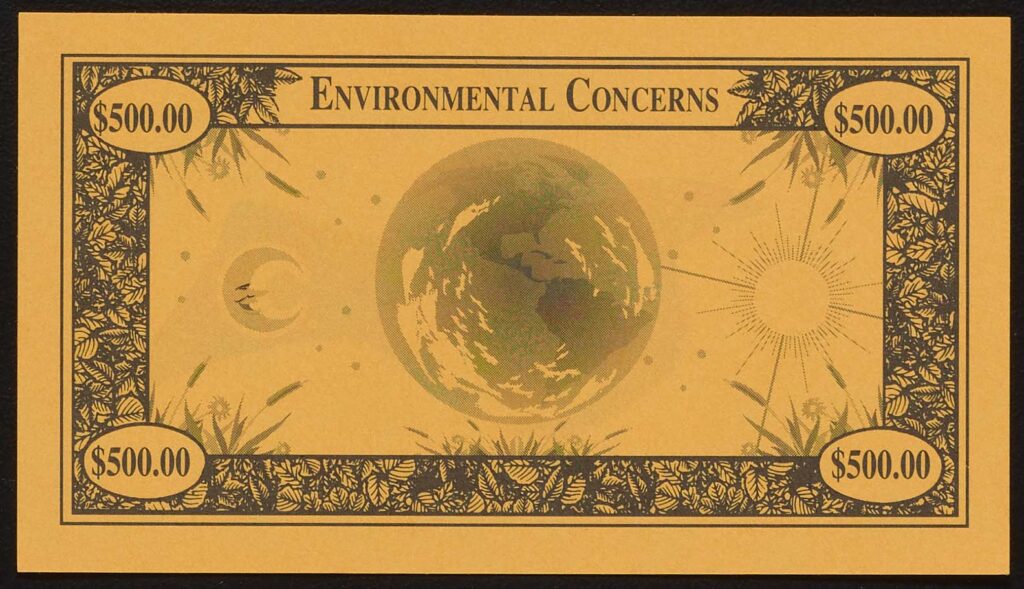

In this Monopoly-styled game, a “recycling center” acts as the “bank.” Players buy “recyclables” and “dumpsters” to collect fines from other players. An image of the Earth between the sun and moon forms the centerpiece of the game’s money.

Though the image on the money is not multicolored, game players may recognize the image of the “Blue Marble,” one of the most reproduced images in history, which was originally captured in 1972 by the crew of Apollo 17. It depicts our blue planet against the black of space.

To date, those three astronauts remain the only humans to have seen the full Earth. The designers of Environmental Concerns adapted the photo, substituting the Americas for the original photograph’s focus on Africa.

A leafy motif frames the bill, suggesting greenery even in the absence of multiple colors. Escaping the frame and poking into the center are what appear to be cattails (Typha), a wetland plant genus common around the world. The game designers likely used cattails to emphasize natural spaces such as marshes. However, ecologists now consider some species of cattails to be invasive. In some parts of the United States, human ecosystem disturbances such as nutrient-rich runoff into wetlands have allowed Typha to proliferate, squeezing out other species of plants and animals. Typha, both invasive and native, complicates how we understand different plants and fauna. A species beloved in one part of the world may be viewed quite differently elsewhere.

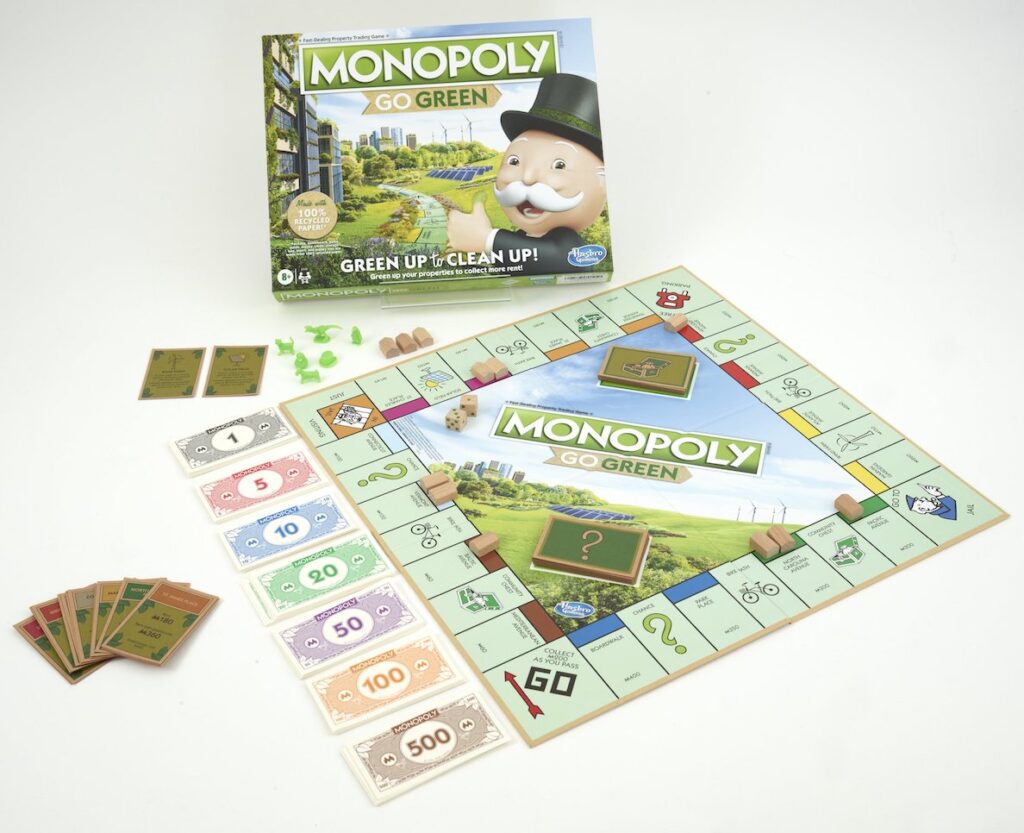

Leaves reappear in Monopoly: Go Green, where the currency in the game is used to buy properties and build greenhouses. Hasbro replaced the familiar imagery on Monopoly money with a leafy background and images of bees, an important pollinating species. Two bees on either side of the center denomination marker have replaced the standard edition’s iconic railroad locomotive and house.

The designers of Monopoly produced the game at a time when global bee populations have collapsed, triggering concerns over the cascading effects of pests, pesticide use, and global climate change. (Though bees are famously cooperative, the Go Green edition does not change its rules to encourage players to work together.)

The changes to the bills’ iconography underscore other changes in this edition of Monopoly. The game’s box notes that its money is made from 100% recycled paper. Hasbro also packaged the Go Green edition without plastic film wrappers, relying instead on paper tape strips. Game tokens made of recycled plastic replace the more familiar metal game pieces. The leaf motif and packaging also highlight a change to gameplay themes: in addition to swapping greenhouses for houses and hotels, the Go Green edition allows players to buy green utilities such as wind energy.

These changes reflect an effort among some game manufacturers to carry environmentalist concerns from the gameplay to the physical games themselves. As the industry group Green Games Guide notes in the introduction to its voluntary guidelines, “from the materials that make up a game to box size and packaging, there are far too many ways that our industry contributes to environmental destruction and wasteful consumerism.” Understanding both the images on the currency and the material of the currency in Monopoly Go Green helps us see how both reinforce the game’s messaging.

Diving deeper into the iconography of board games allows us to explore the interconnections between board games and the worlds they reflect. They can be richly layered. Game designers often imbed some of the pressing issues of their time periods into the designs of play money. And the ongoing presence of money in these games alone reflects the persistent presence of money and the market in our understandings of how to solve environmental challenges.

The Institute’s museum education team partners with Philly Touch Tours to offer a more meaningful history of science experience.

Mapping Philadelphia’s industrial past with digital tools.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.