Life on ‘The Mesa’

The Manhattan Project forged a city in the desert at Los Alamos.

The Manhattan Project forged a city in the desert at Los Alamos.

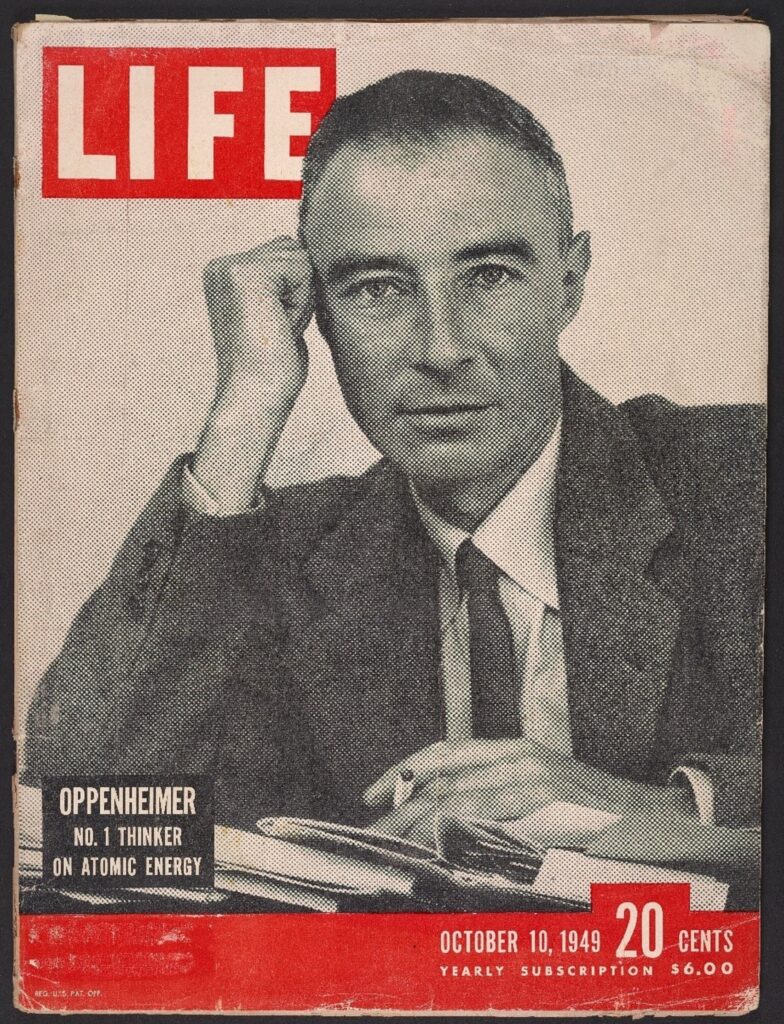

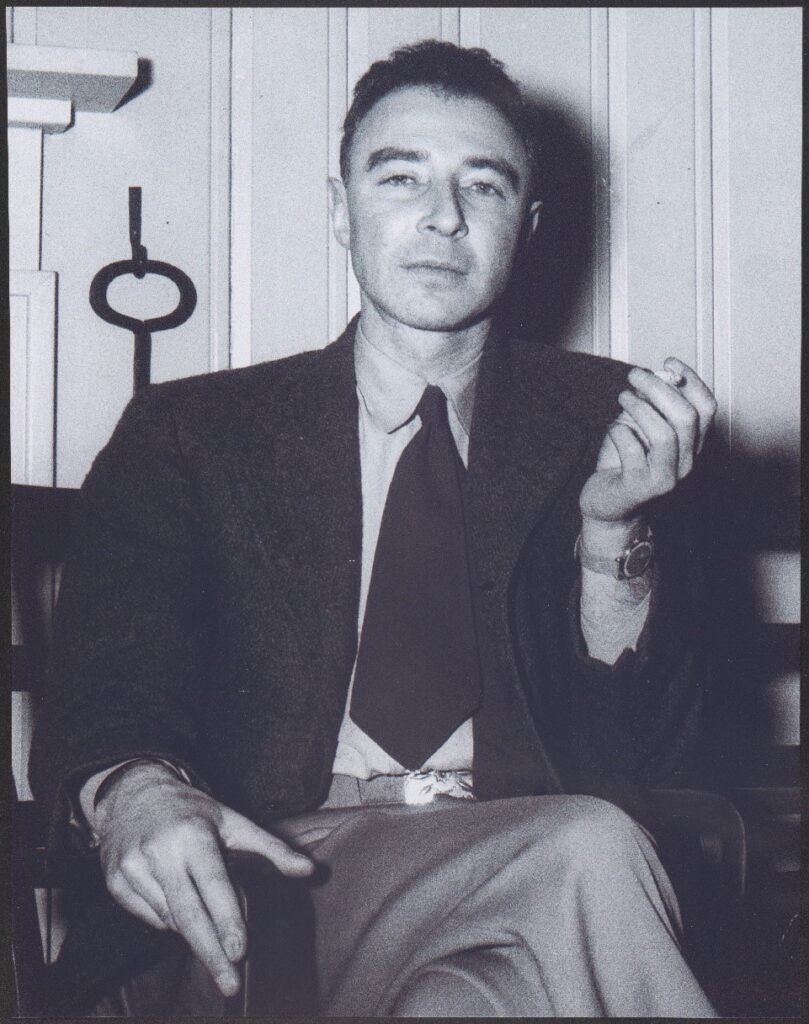

For two years beginning in the spring of 1943, many of the world’s brightest physicists, chemists, and engineers participated in an intense government program to create the world’s first atomic weapons. In complete secrecy, this cadre of elite scientists converged on a small, remote mesa in Los Alamos, New Mexico. They theorized about the inner workings of the atom, devised novel ways to split them, and in the process, constructed the deadliest weapons in human history.

Inhabitants of the site spent their days engaged in both cutting-edge science and moral discussions about life and death, but for the most part, life continued at Los Alamos as if it were any other American town. The people worked hard, played hard, fell in love, and in a great many cases started families. In the words of journalist Ellen Newman, life at Los Alamos during the war was “part summer camp, part science fair, and part college campus under lockdown.”

Located on the eastern slope of the Jemez Mountains on the Pajarito Plateau, Los Alamos is as beautiful as it is remote. The site was selected by J. Robert Oppenheimer to centralize the research being conducted around the country on the Manhattan Project. The remoteness of the area appealed to military planners, but it was the beauty of the surrounding landscape that Oppenheimer used to recruit his select team of scientists. Ruth Marshak, wife of physicist Robert Marshak, described her first impressions of the area:

The remoteness of the area meant that an entire city would need to be built from scratch, including houses, schools, stores, a post office, a hospital, a fire department, and a power plant. Doctors, veterinarians, garbage collectors, and countless other specialists would also need to be recruited for the site to function efficiently. Almost overnight, Los Alamos had become a boomtown. In many ways, the construction of Los Alamos was like that of any of the other single-industry company towns scattered across the U.S., particularly those in the mining and timber industries. But at Los Alamos, the industry was atomic weapons.

By 1943 scientists and their families, along with the most sophisticated scientific equipment of the day, arrived from all parts of the United States and Europe. Staff included the best and brightest of the scientific community, including Enrico Fermi, Hans Bethe, Richard Feynman, John von Neumann, Emilio Segrè, Edward Teller, and others. Many of the Los Alamos scientists were already leaders in their fields and had contributed to the very foundations of modern physics and quantum mechanics. Several had won Nobel Prizes before the Manhattan Project; many others would win in the decades that followed.

Married scientists were permitted to bring their families to the site, a fact that proved key in the recruitment process. Others were fresh out of graduate school, single, and eager to start a family. At its height, there were approximately 640 women working at the secret city, about 11 percent of the total work force. Some were the spouses of scientists, but nearly half were scientists and mathematicians in their own right.

For those working on the project, the stakes were unbelievably high. A typical work week was 12–14 hours a day, six days a week. But on Saturday night, they let loose. Several events were usually scheduled for every Saturday evening, and these events, fueled by large quantities of alcohol, soon became an integral part of life in Los Alamos.

Scientists and their families also relaxed by participating in a variety of camp-like activities such as hiking, skiing, and horseback riding through the mountains. Teller cleverly described life at Los Alamos as “a wilderness reserve for physicists.” The theater and square-dancing clubs were also popular and hosted frequent events in Fuller Lodge, a three-story log structure that served as the heart of the Los Alamos community. The lodge was also home to the Keynotes, the project’s very own orchestra.

The secret nature of their work coupled with their isolation from the rest of the world created a strong sense of community among the site’s inhabitants. Many lifelong friendships were made there and many new romantic relationships were formed. Almost from the very beginning, the military hospital at Los Alamos became notable for its high birth rate, which greatly exceeded that of any other military hospital in the country. This fact caught military planners off guard, as the local hospital had been equipped to provide care for industrial accidents, not pregnancies.

By 1944 medical director Stafford Warren wrote to General Leslie Groves, the head of the Manhattan Project, stating, “Approximately one-fifth of the married women are now in some stage of pregnancy.” In total, 80 babies were born in the first year at Los Alamos. By war’s end, that number exceeded 200, and by 1949 over 1,000 babies were born at the site.

Groves was not at all pleased with the extracurricular activities of the staff and insisted Oppenheimer take steps to stop the “baby boom.” Oppenheimer, however, did not feel that population control was part of his job description and declined to do anything. Moreover, Oppenheimer’s wife Kitty was pregnant at the time. Grove’s complaint soon spread across the community and as a result, a limerick grew in popularity among the staff:

Since the town of Los Alamos did not officially exist, everyone born at the site had “Post Office Box 1663” listed as the place of birth on their birth certificate. By war’s end, in a unique historical quirk of the time, over 200 babies had officially been born in a post office box.

In the years since, countless biographies and memoirs have been published that recount life at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project. It was a time of intense academic research and development with literal life and death consequences, but for most, life simply went on and the residents of Los Alamos made every attempt to enjoy it to its fullest.

Today the site operates as the Los Alamos National Laboratory, but to the many scientists and engineers who lived there during World War II, it was called “The Mesa.” In military jargon, it was known as “Site Y,” and affectionately, many of its inhabitants referred to it as “Shangri-La,” a mythical mountain utopia isolated from the rest of the world.

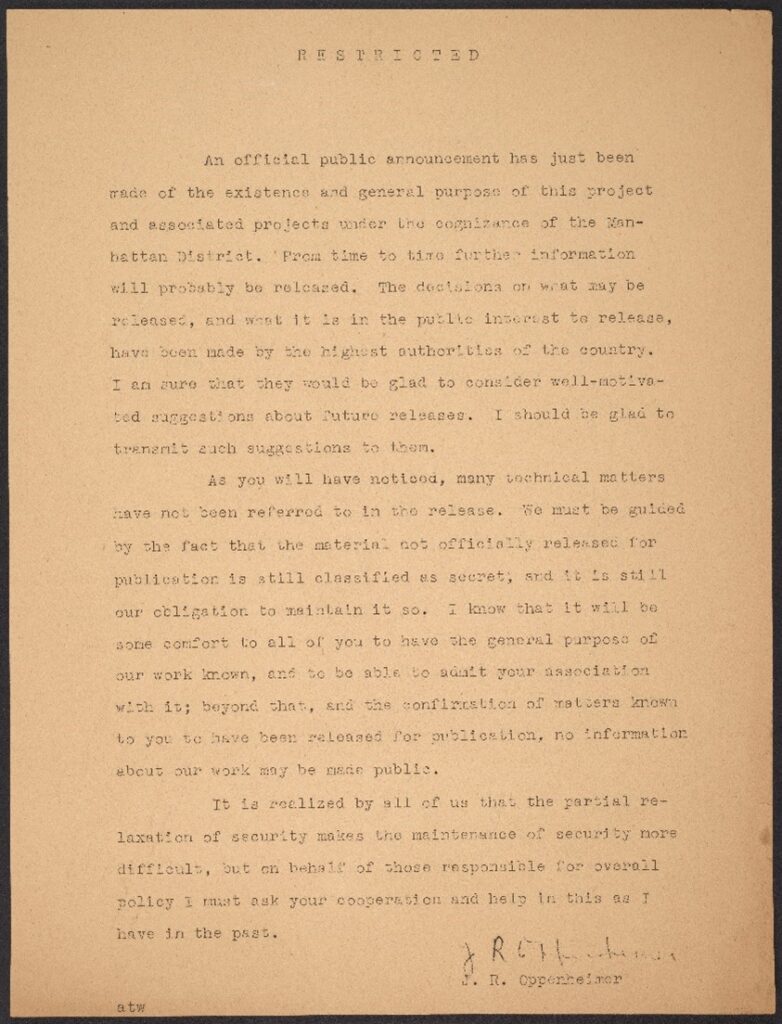

The Science History Institute holds the papers of two Manhattan Project scientists: Spofford Grady English and Richard W. Dodson. While English worked on the project as part of Glenn Seaborg’s group at the University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory, Dodson lived at the secret Los Alamos site, and his collection offers a glimpse into the normal lives playing out in the most unusual circumstances.

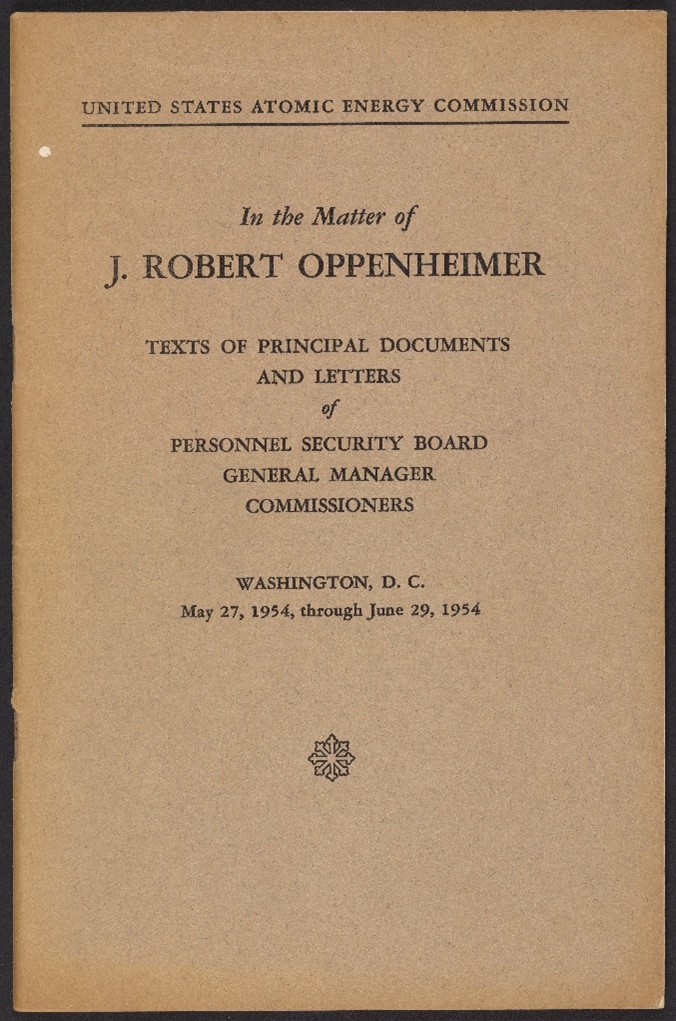

If you are interested in viewing the Institute’s collections related to Los Alamos and the Manhattan Project, we invite you to our library open house on April 10, which will feature the items pictured above, alongside a variety of items related to the suspension of Oppenheimer’s security clearance in 1954.

Featured image: The Lodge at Los Alamos as pictured on a sheet of stationary, from the Richard W. Dodson Papers, Science History Institute.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.