Here Be Dragons

Celebrate the Year of the Dragon with some of the legendary creatures in our collections.

Celebrate the Year of the Dragon with some of the legendary creatures in our collections.

This February kicks off the Chinese New Year and the Year of the Dragon. And dragons abound in the Science History Institute’s collections, including examples of the legendary creatures that date back to the 17th century!

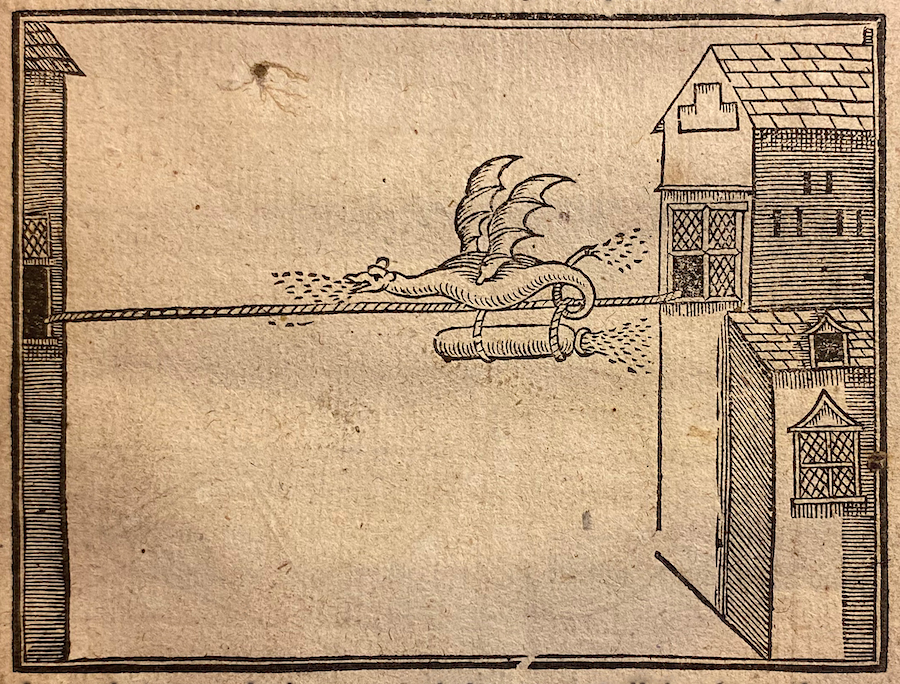

In his 1635 work, The Mysteries of Nature and Art: in Foure Severall Parts, English author John Bate describes how to make a flying dragon fireworks display. He recommends making a lightweight dragon out of wood or thin whalebone with a Muscovy glass (mica sheet) cover. The dragon could then be suspended on a rope, with rockets tied below and fireworks placed in the body. Bate’s dragon would have been quite the spectacle, sparking from the wings, tail, and mouth, and shaking as it “runnes along the line.”

Evidently, dragons held some popularity as topics of pyrotechnic entertainment in the 17th century. This schematic for a ground-level fireworks display comes from Artis Magnae Artilleriae (The Great Art of Artillery). Written in 1650 by artillery general Kazimierz Siemienowicz, the book served as an important instructional manual for both military and civilian users.

By providing recipes and instructions for a profession dominated by local knowledge and experts, Siemienowicz helped expand knowledge about pyrotechnics, rocketry, and artillery. Writing down the recipes for artillery and fireworks and publishing them for distribution allowed knowledge to travel beyond local experts, and Artis Magnae Artilleriae became a standard manual across Europe.

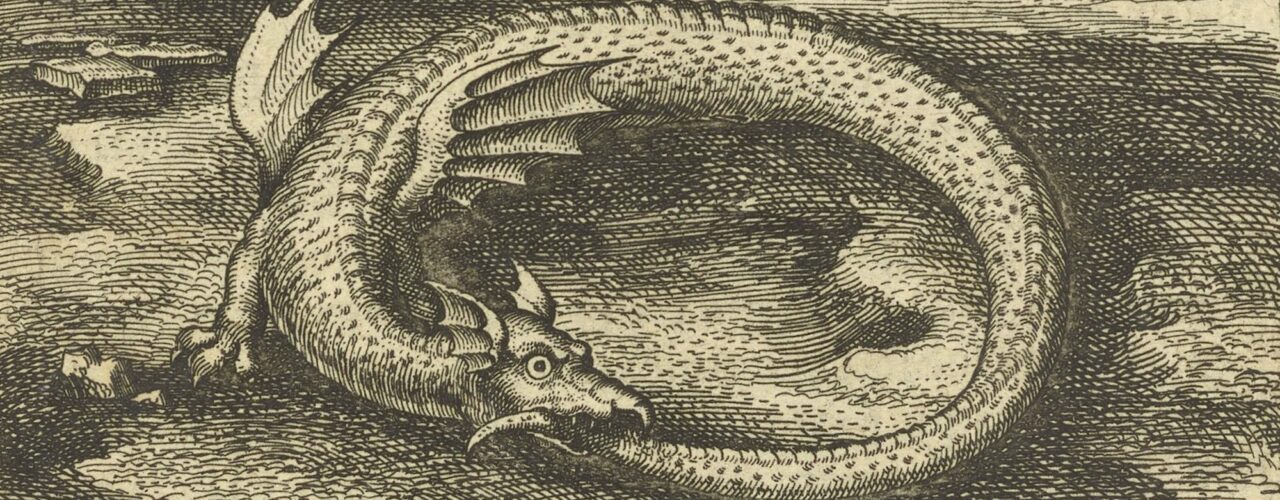

In the early 17th century, English cleric Edward Topsell compiled a bestiary, a book describing real and imagined animals consider beasts. This included, apparently, dragons. Topsell originally published a separate volume for four-legged animals and another for snakes. In 1658 they were reprinted as a single volume and published as The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents.

One of Topsell’s more fascinating entries concerns the dragons of the world that come in many different forms:

Topsell’s work also contains descriptions of dragons found in Europe, Asia, and Africa, with the descriptions often launching into their respective habitats, diets, and historical significance. It includes stories from the ancient world as well. The dragons of Phyrgia—now part of Turkey—received an extensive description. Although some hungry dragons of the area hid themselves and ambushed humans and domesticated animal herds when desperate, the dragons were nonetheless food connoisseurs of a sort.

As Topsell reports, the dragons “greatly preserve their health (as Aristotle affirmeth) by eating of wilde Lettice, for that they make them to vomit, and cast forth of their stomach whatsoever meat offendeth them, and they are most specially offended by eating of Apples, for their bodies are much subject to be filled with winde, and therefore they never eat Apples, but first they eat wilde Lettice.”

Dragons seem to have stepped (flown?) out of our collections in the 18th and 19th centuries, but they returned in the form of plastic.

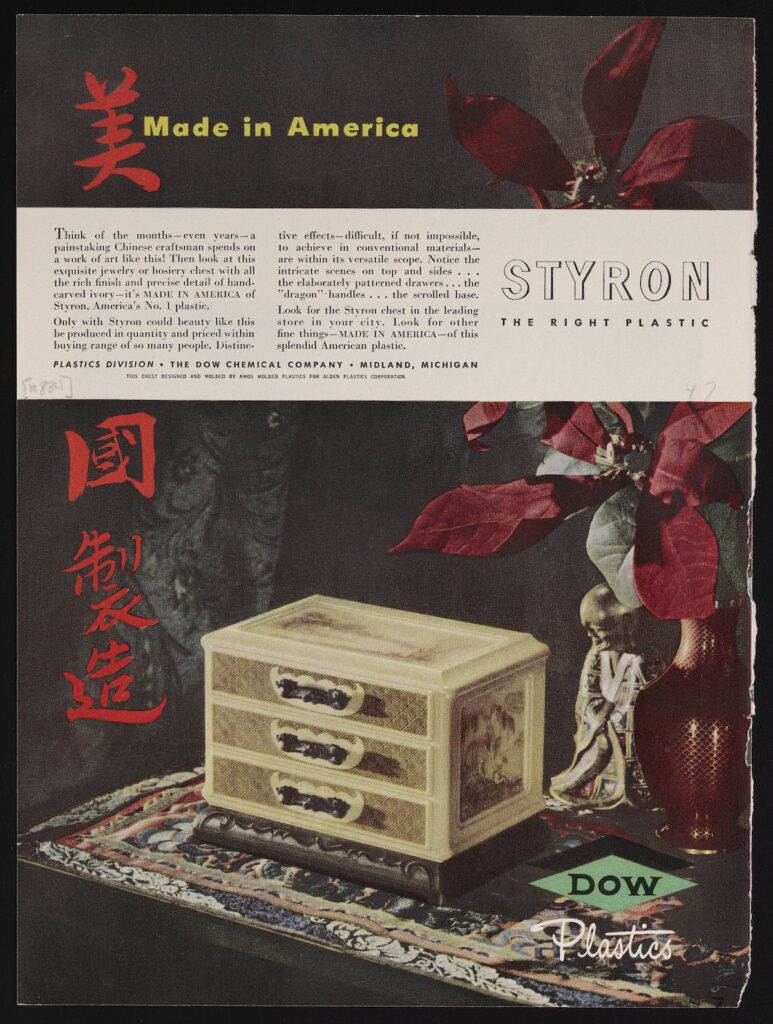

In this ad from our extensive collection of mid-20th-century Dow Chemical Company advertisements, dragons form part of a Styron plastic chest. Durable and versatile, Styron was part of the post-World War II plastics proliferation that saw the material appear in everyday consumable goods.

The jewelry chest pictured features imprinted patterns, a 3D relief on the top and sides, and drawer handles fashioned into black dragons. Details such as the dragon handles showed mid-century consumers that plastic could bring luxury goods to the masses.

According to the ad, “a painstaking Chinese craftsman” might have spent months or years to create such a product out of ivory in the past, but plastics enabled consumers to enjoy once-rare items: “Only with Styron could beauty like this be produced in quantity and priced within range of so many people.”

If the Styron chest was an example of U.S. manufacturing strength, by the end of the century plastic had become a ubiquitous material. Even products designed as durable goods could find themselves relegated to unsightly trash, which is what happened to a plastic dragon Lego toy.

In 1997 this actual Lego piece was on its way to store shelves via the Tokio Express cargo ship when a rogue wave swept 62 shipping containers off the vessel near the English shore. One of these containers was filled with nearly five million Lego pieces. Ever since, Legos have been washing up on the beaches of Europe and even further abroad.

More than 30,000 of the Lego pieces were dragons, including this one, which was found by siblings Lucy and Edward Thresher and is now part of the Institute’s collections. Made of tough plastic designed to survive the hardships of abusive play by children, this piece demonstrates just how durable plastic can be. Even after decades in the ocean, it remains in playable condition, only slightly worse for wear. Of course, this durability contributes to the problem of plastics in the ocean and other environments: the material persists, contributing to pollution and contamination.

Whether explosive, bearded, footless, winged, or plastic, many dragons exist in our extensive collections. From all of us at the Science History Institute, we wish you a happy and prosperous Year of the Dragon!

Special thanks to James Voelkel and Ashley Augustyniak for their assistance.

Featured image: Emblema XIV. Hic est Draco caudum suam devorans (Emblem 14. This is the Dragon that devours his own tail), from Atalanta Fugiens, 1618.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.