Her Booke

What marginalia can tell us about a book’s former owners.

What marginalia can tell us about a book’s former owners.

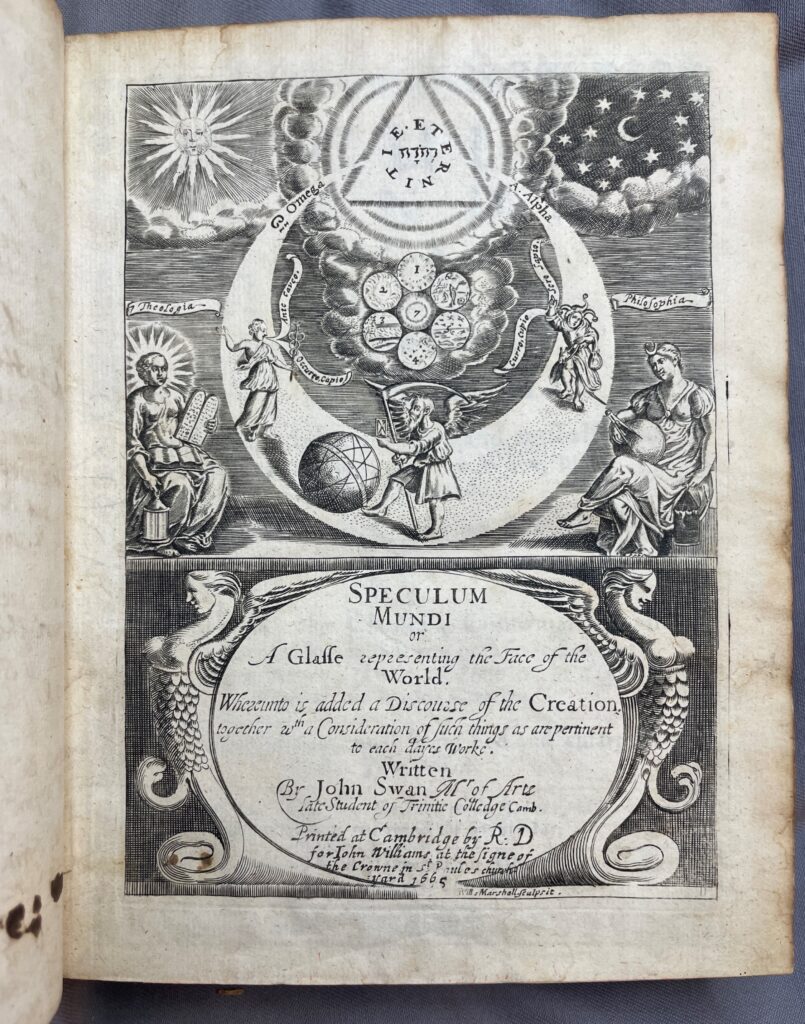

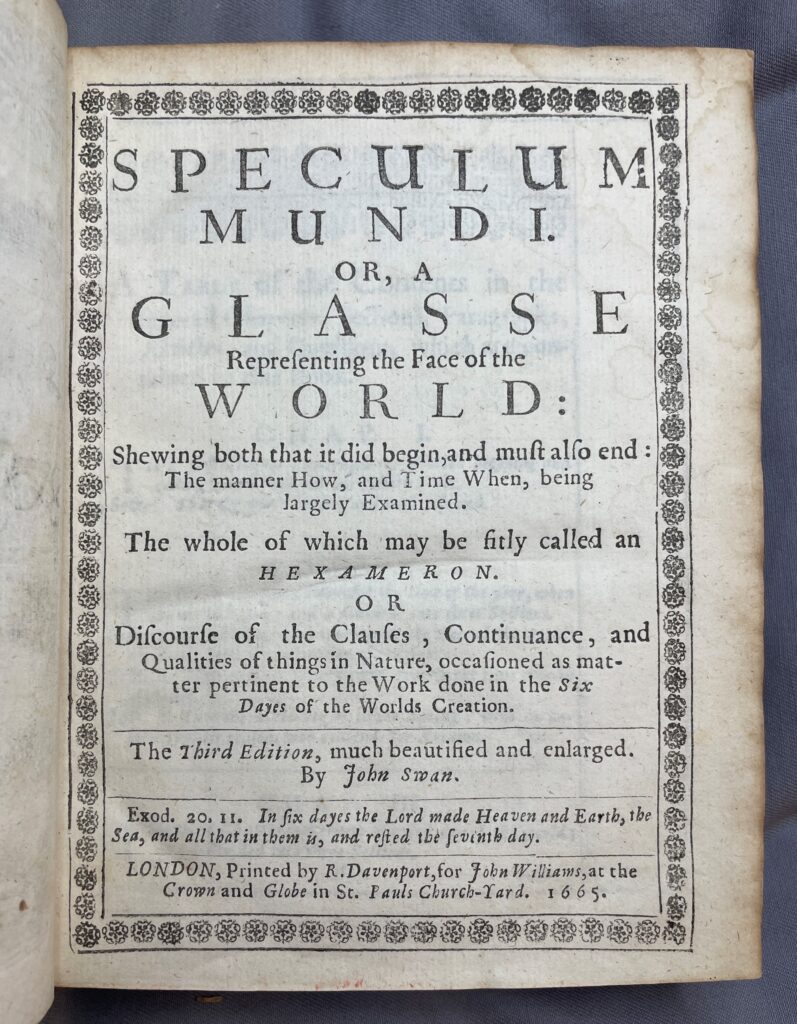

The Speculum mundi (Mirror of the World) published in 1665 expounds on natural history within the framework of the six days that God created the world according to the Bible. It details astrological phenomena, the minerals of the Earth, descriptions of animals, and the properties of plants—all with a mixture of science and scripture. But what interests me most about the Science History Institute’s copy of this book are its former owners and their apparent interests.

Frontispiece and title page of Speculum mundi.

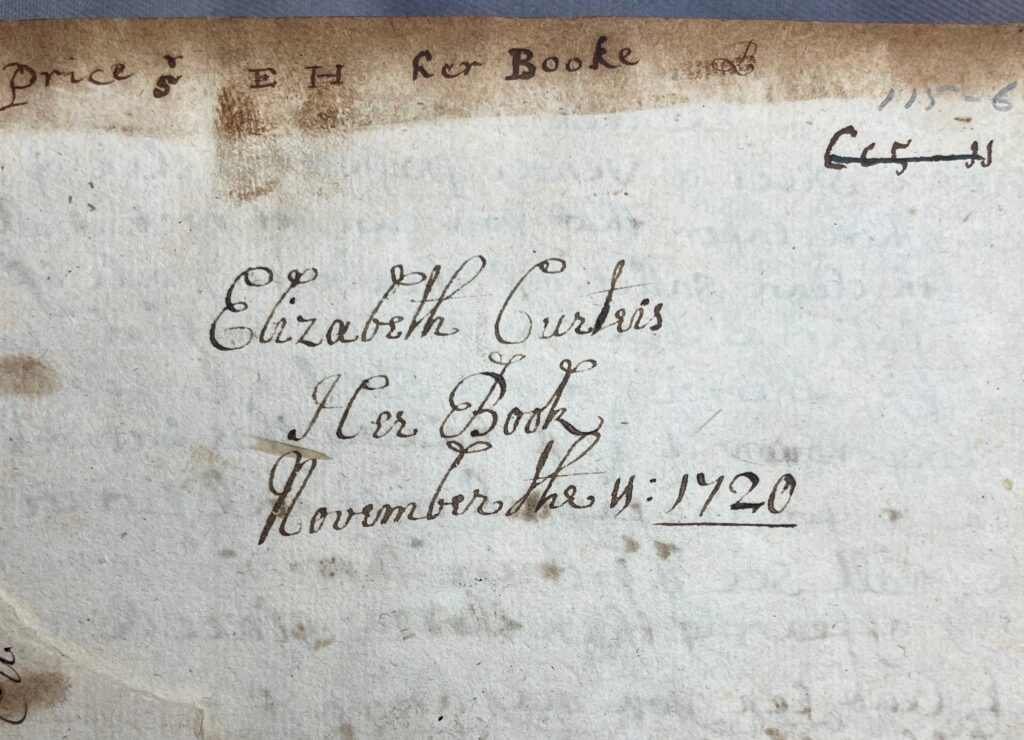

There are two names on a flyleaf at the front of the book, both female. One inscription reads, “E H her Booke,” and the other, “Elizabeth Curteis Her Book November the 11: 1720.”

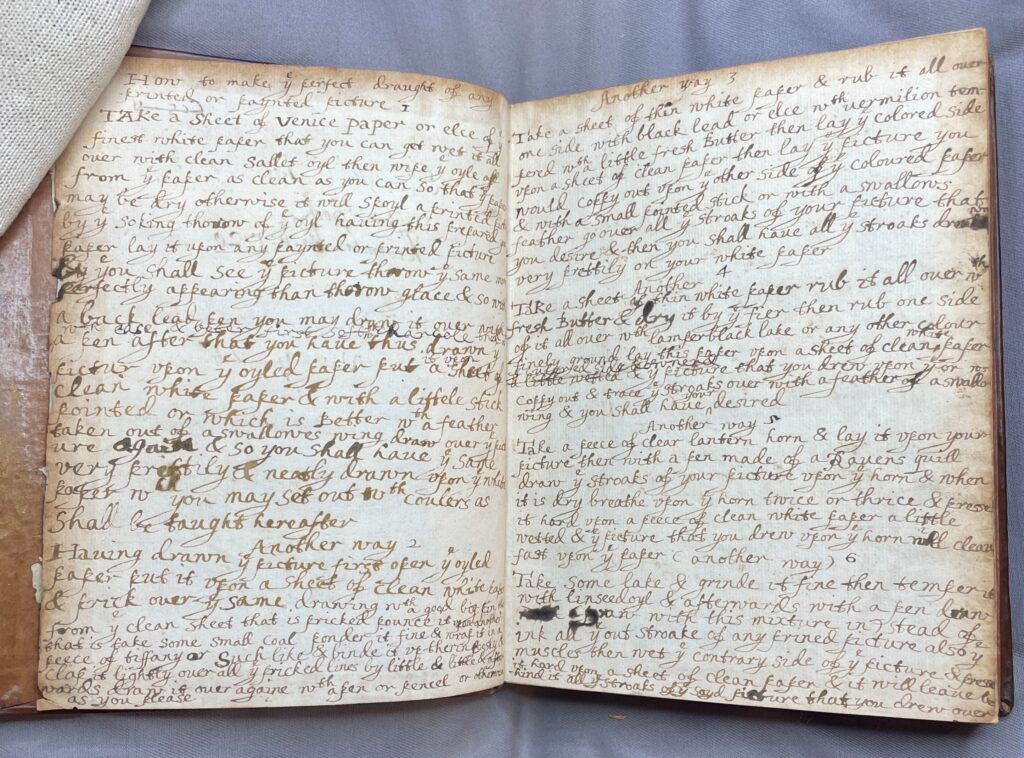

There is very little marginalia along the text block within the book, but there are whole sections of another book copied onto five pages of the flyleaves at the front and back of the book. The handwriting leads me to believe that EH was the scribe of these pages, and because her spelling of the word book includes an “e” at the end, I also believe her to be the earlier owner of the two since that spelling was common in the 1600s.

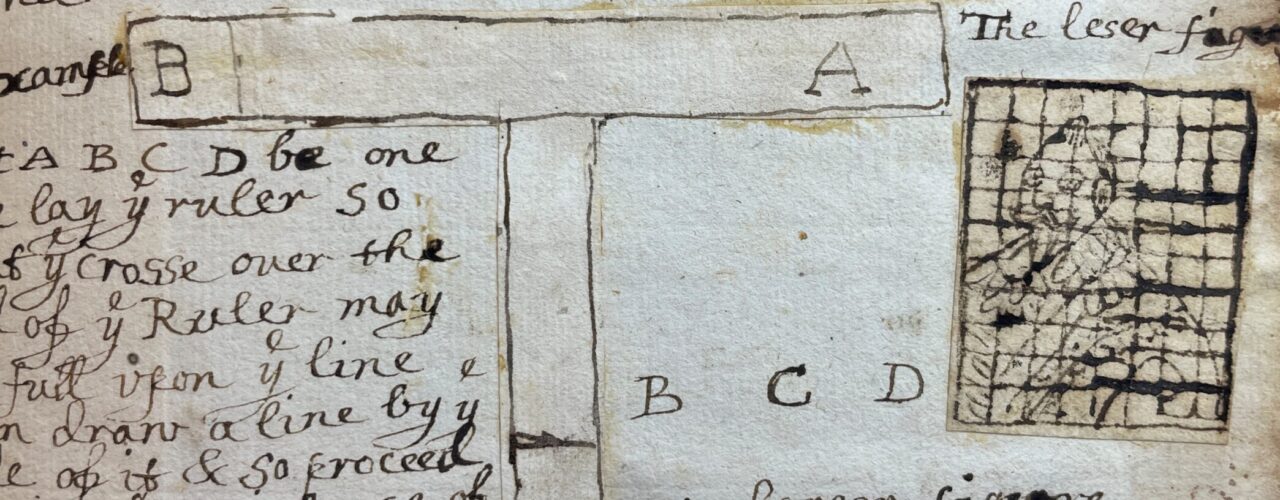

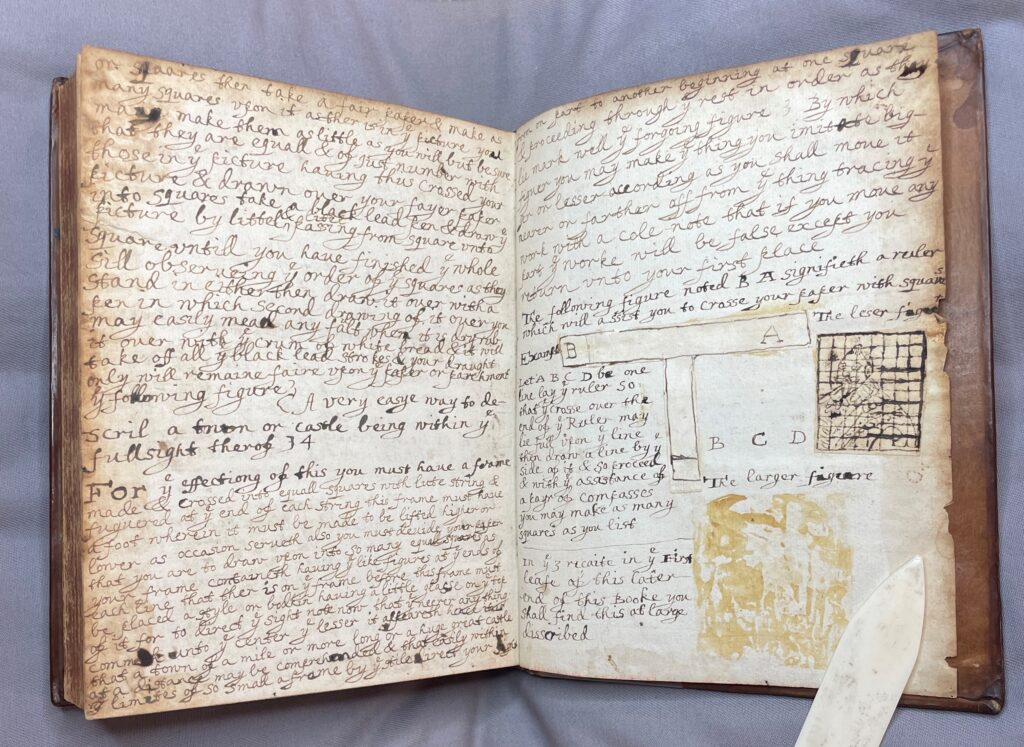

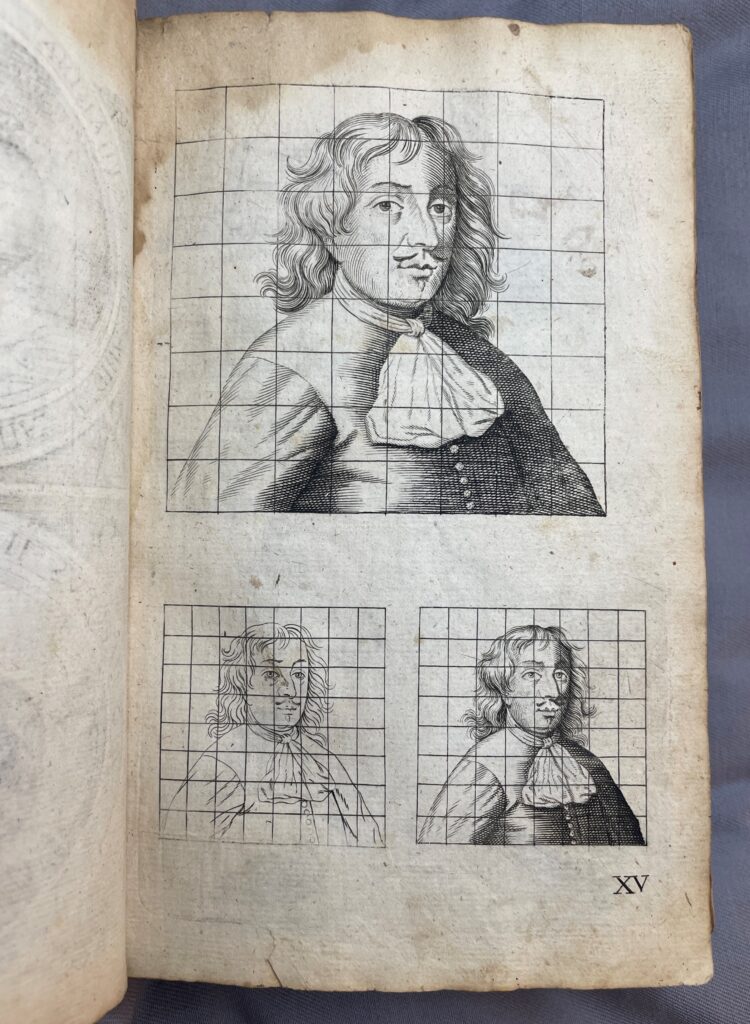

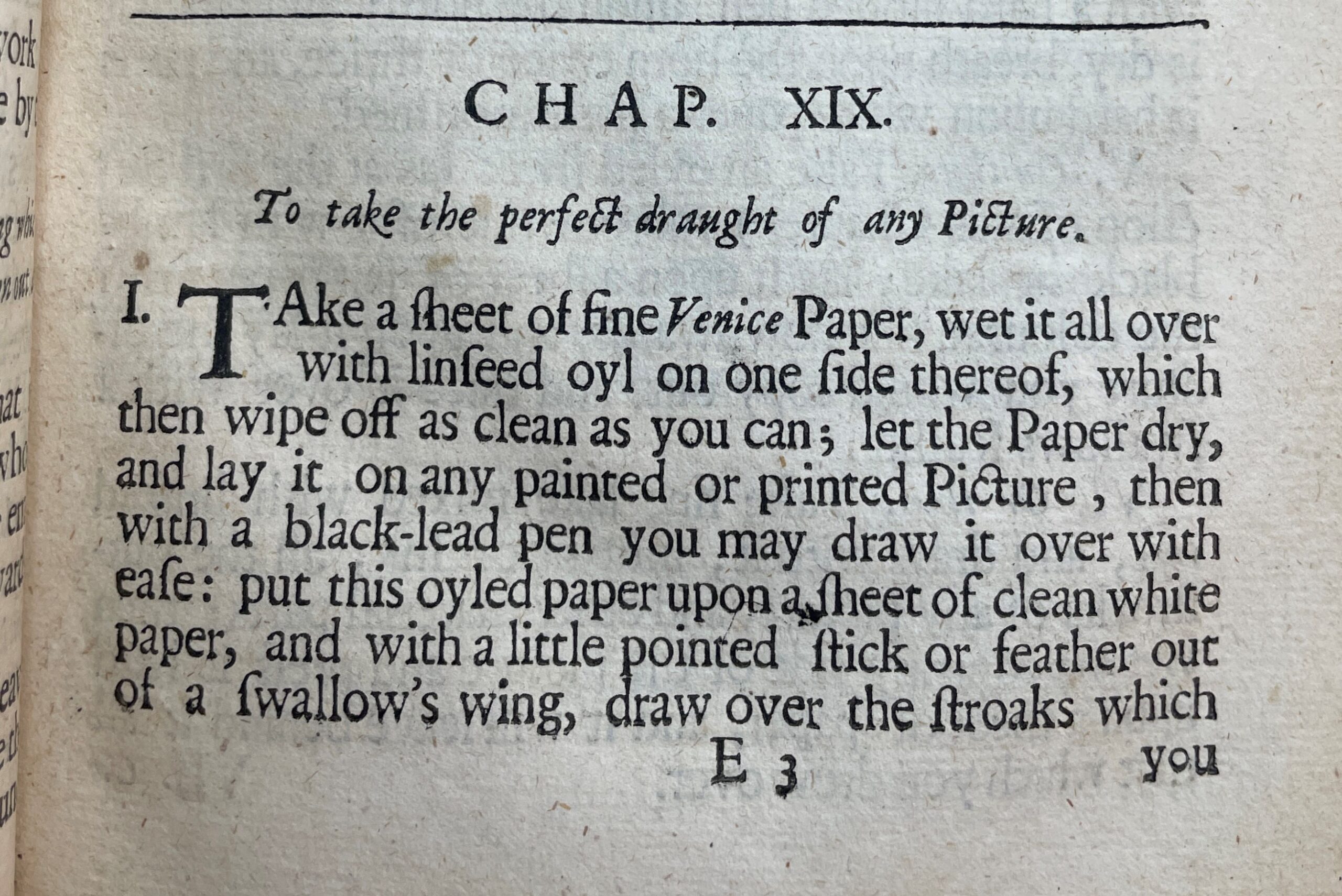

This handwritten text contains directions on copying prints and paintings (“How to make ye perfect draught of any printed or paynted picture”) and sketching landscapes (“A very easye way to describe a town or castle being within ye fullsight therof”). This makes me wonder: Who were these women? What did this book mean to them? Why did they add art instructions to a book on natural history? Part of me wants to write fan fiction about what I imagine their lives were like, but today we will stick to what is in front of us.

The two women were probably English, and I have found a “Curteis” family based in Kent but have yet to pin down the exact Elizabeth or who an EH could have been. In the early modern period, property rights for women were minimal. Husbands or the closest male relative was usually favored by law, but many women were able to collect books on their own and there is evidence, such as signatures, of several women-curated libraries or small book collections. These collections are now mostly dispersed throughout rare book libraries and personal collections, but librarians and historians have been working to identify these books through projects like the Early Modern Female Book Ownership blog.

Beyond simply owning the book, women also owned the space within the book, as is argued by Katherine Acheson in her book Early Modern English Marginalia. Our readers were not passive: they took up space; they were collectors, curators, editors. They took an author’s work and made it their own, something assumingly more usable and valuable to themselves. They turned reading and book ownership into a creative practice.

But why use the flyleaves of this book over loose leaves or a common notebook? Paper was not as scarce at the time as many tend to believe; even these marginalia include instructions for the amateur artist to take sheets of paper and soak them in oil to create tracing paper. If paper was scarce to our reader, they would have trouble practicing the described techniques. It’s possible that this book was their only writing space when they were in the presence of the original art manual. Though you might think they would later cut it out or copy it elsewhere to keep it separate, or at least not go through the trouble of gluing down the hand-drawn graphics as seen on the last page.

We know that this marginalia is copied text and not original material written by EH because it so closely matches the text in books of art instruction from the time. During the early modern period, copying was practiced extensively, usually into commonplace books. In trying to track down the art manual that was the source of the Speculum mundi marginalia, I have found that even copying in publishing was widespread. Many of the contemporaneous art manuals I consulted list these same techniques and may only change a few words in their descriptions.

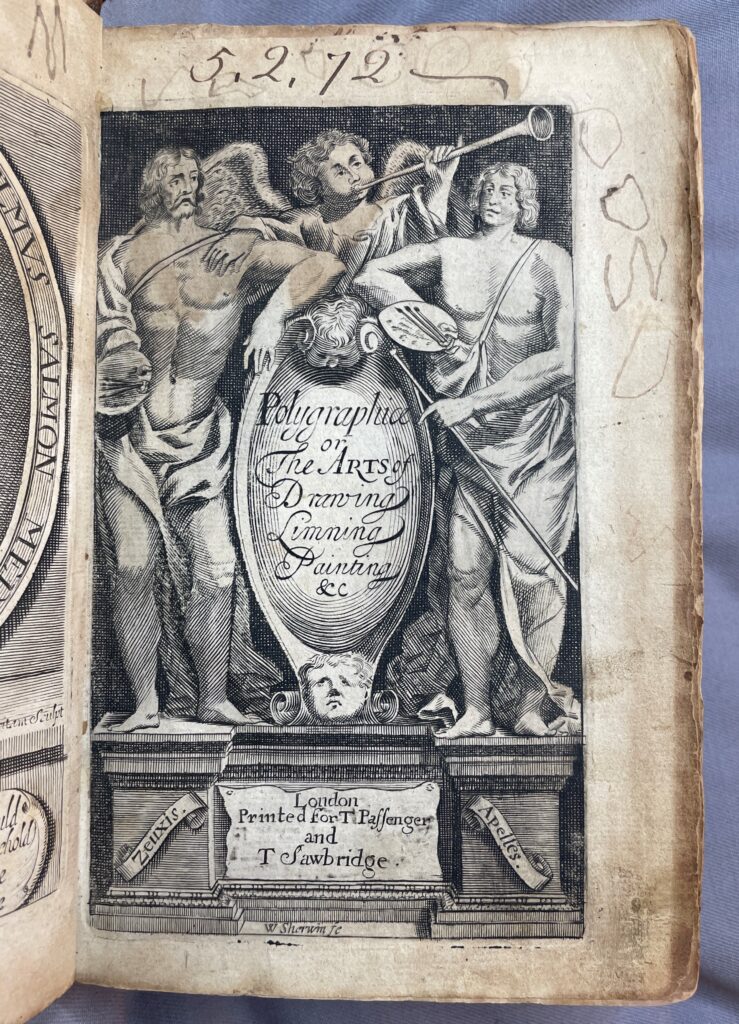

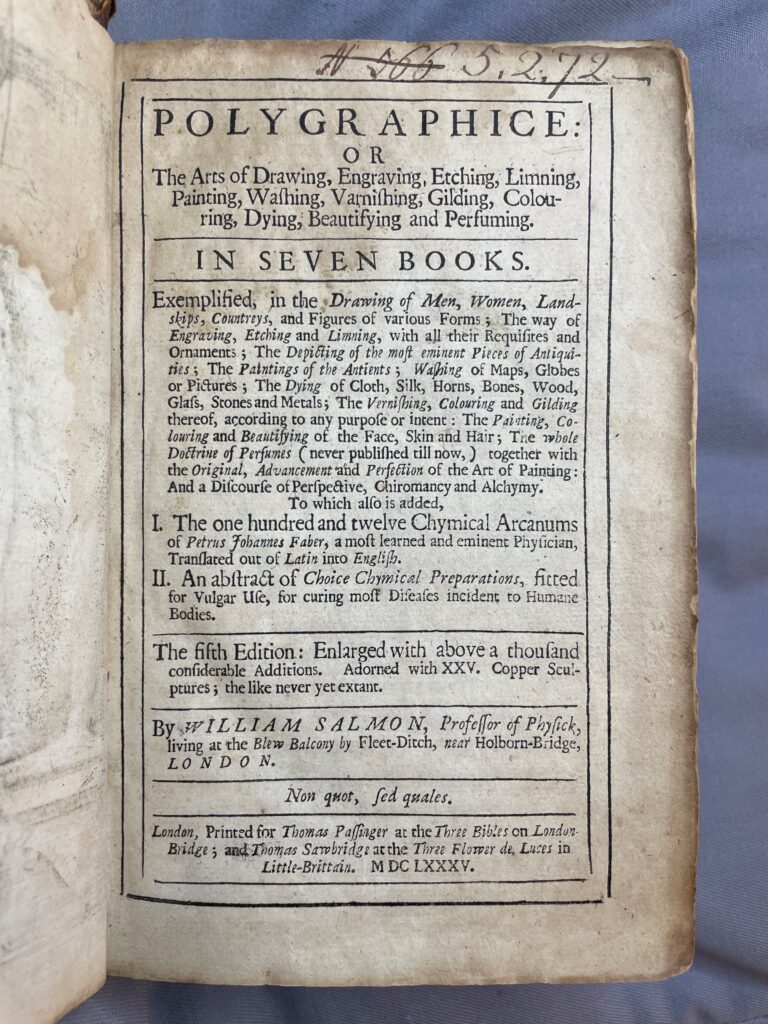

One of the closest examples I found was a book in our collection from 1685 titled Polygraphice, or, the Arts of Drawing, Engraving, Etching, Limning, Painting, Washing, Varnishing, Gilding, Colouring, Dying, Beautifying and Perfuming. This was written by William Salmon, a physician and prolific author on a variety of subjects, who was well known for “compiling” other people’s words.

Frontispiece and title page of Polygraphice.

Drawing instruction in Polygraphice.

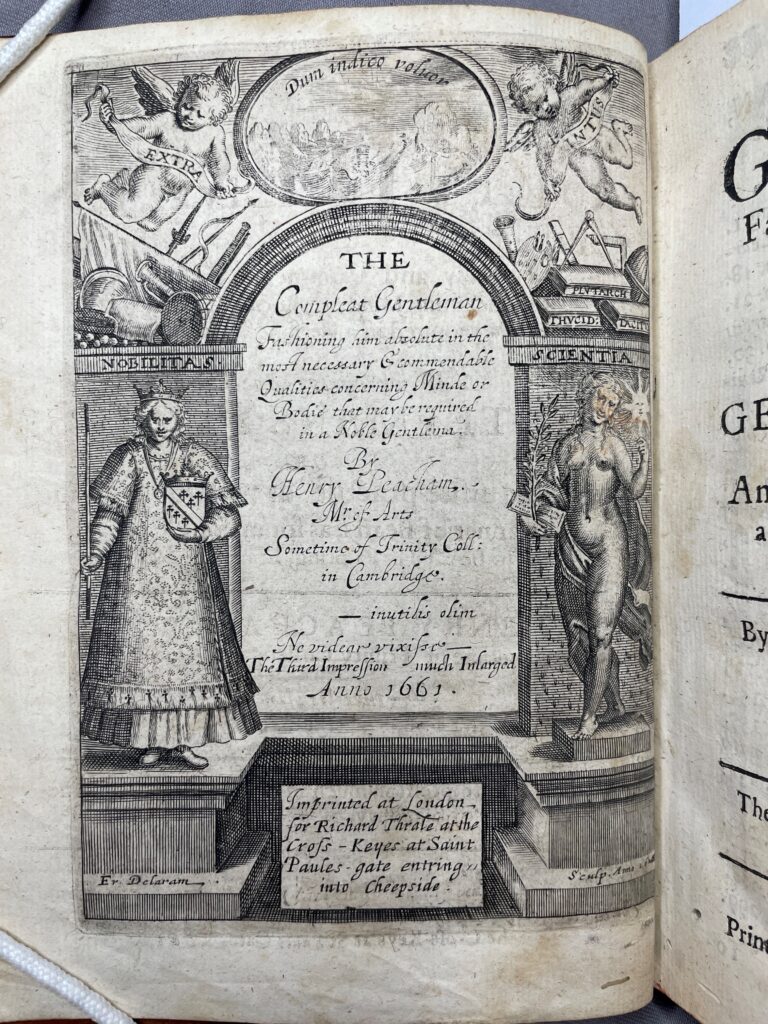

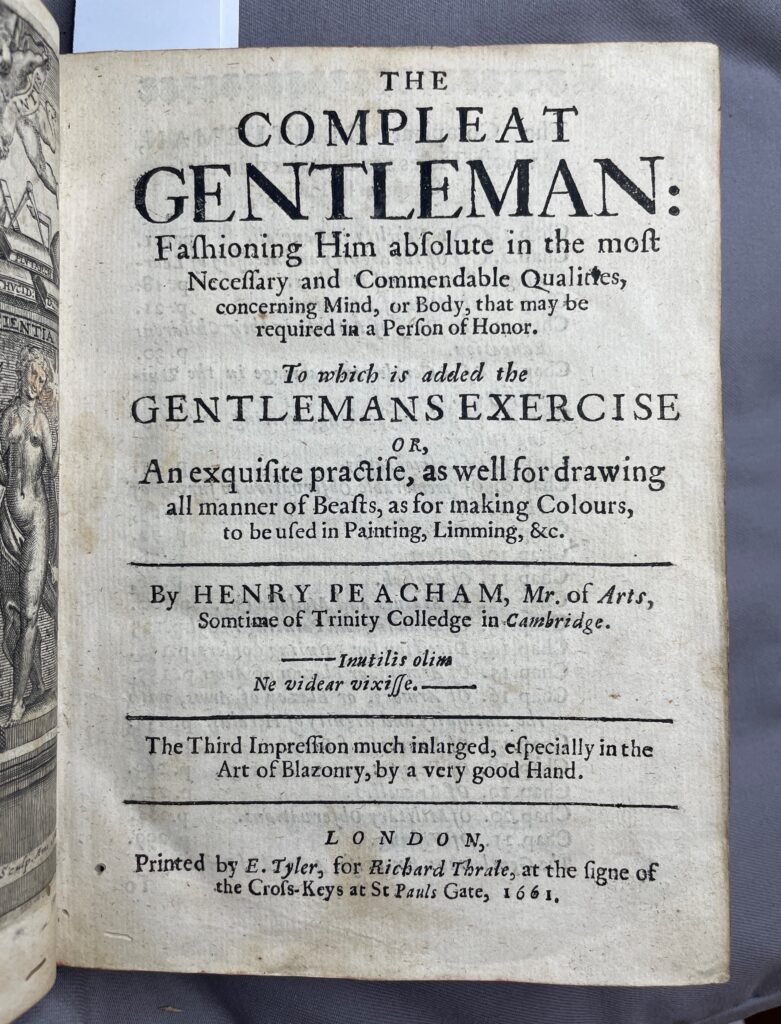

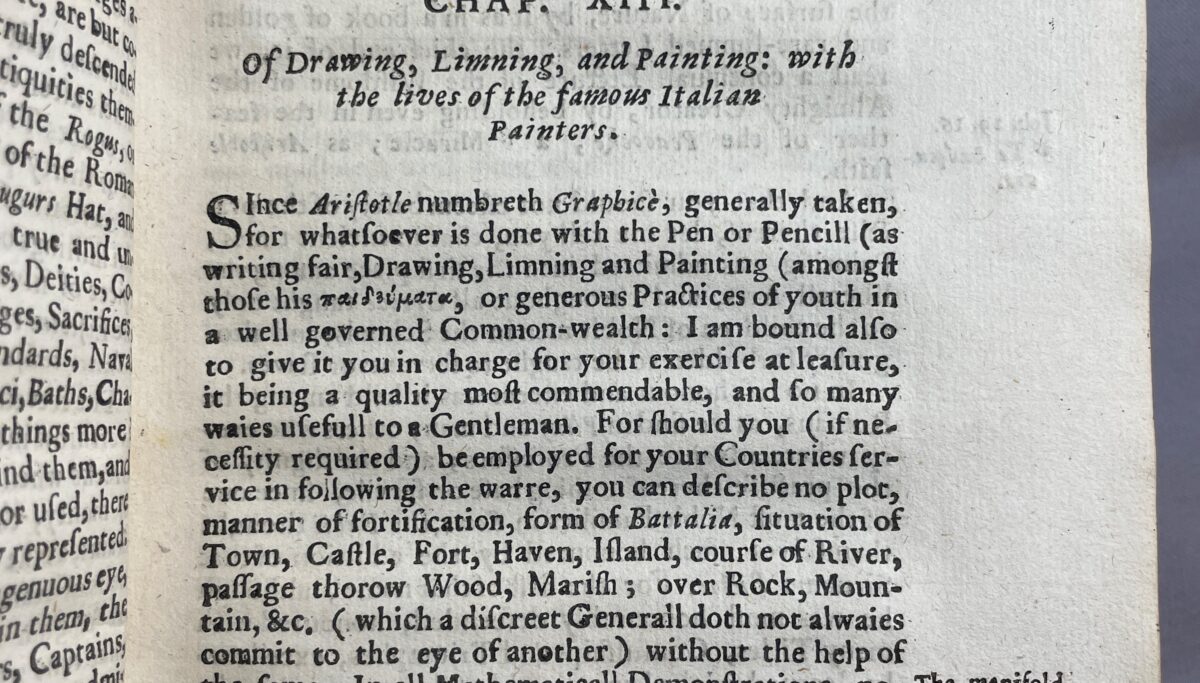

What is the significance of this marginalia’s being art instruction? During the Renaissance to the early modern period, amateur art transformed from a skill taught mostly in military academies for sketching and describing battlefields into a status symbol for a growing middle class. In Protestant England, it also shifted from being thought of as a blasphemous leisure activity to being a suitable pastime for gentlemen and ladies. For instance, art instruction is included alongside instruction on etiquette for a nobleman in Henry Peacham’s The Compleat Gentleman. Once the practice of art caught on, it became extremely popular, and art manuals became much more accessible than a private art tutor so books like William Salmon’s sold very well.

Frontispiece and title page of The Compleat Gentleman.

Drawing taught people a new way of seeing and observing. Our reader’s book is on natural history, which was a science based on description of the natural world. It was important for those interested in natural history to also cultivate their drawing skills since sketching from life was a way to document first-hand experiences. This line of thinking offers clues but doesn’t fully satisfy my question of why EH would collect art techniques in a book on natural history. I have cookbooks stuffed with clipped recipes from elsewhere, but that collection never strays from the topic of cooking.

In Ann Bermingham’s Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art, she discusses the spread of paper as a medium of information revolution. She points out that paper made access to knowledge, both verbal and visual, more widespread but also more private. I wonder if our readers considered their act of collecting this book-inside-a-book a personal and private act. Were they putting this collected text somewhere safe, where they could find it again, but closed to those who didn’t know where to look? It’s a beautifully bound book: the spine has been replaced but the boards (front and back cover of the binding) are original, so it certainly was a well-cared-for possession.

We might not ever be able to fully answer the question of who these women were and what this book and added text really meant to them. But this marginalia does give us a peek into their lives, their activities, and the objects they thought enough of to mark as their own.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.