Greetings from the Nobel Institute!

Postcards of travel and science.

Postcards of travel and science.

Despite having easy access to email, social media, and text messaging, I still send postcards to keep in touch with others while traveling. While on vacation this summer, I took time to ensure each postcard I purchased would match the recipient. From sled dog photos for my dog-owning brother to historic city maps for my fellow historian friend, I was able to share different parts of my adventures that connected with each of them.

Historians can use such postcards to reveal biographical details about both the sender and the recipient. Geography, dates, and networks (personal and professional) can be pieced together from existing fragments of correspondence. Postcards are also considered “in scope” for those of us who collect and preserve the history of science. Curators collect correspondence from scientists and engineers to learn how they accessed information, formulated hypotheses, and were influenced by mentors.

Let’s take the collection of postcards in the Institute’s Papers of Georg and Max Bredig as an example. The Institute has previously shared the story of the Bredig family’s harrowing escape from Nazi-occupied Europe. Today, I’m going to focus on the professional and personal postcards exchanged prior to the family’s flight for survival. During these years, Georg became Professor for Physical Chemistry at the Technische Hochschule in Karlsruhe, Germany, in 1911 and remained there until the National Socialists assumed power in 1933, forcing him to retire.

This small sample of postcards was exchanged between 1901 and 1934. I chose them from more than 200 in the collection to represent the diverse scope of the content and geography. All English translations were provided by curator Jocelyn McDaniel and were made possible through a grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources.

Georg Bredig sent a silly postcard to his wife Rosa in 1901 from Leipzig, where he was attending the anniversary celebration of the city’s Chemical Society. His handwritten note is charming and brief: “Dear Sweetheart, warm regards from your fickle husband, Georg!” The image on the front of the postcard includes comic representations of nine chemists, with Georg writing their names above each caricature. His professors Wilhelm Ostwald and Ernst Otto Beckmann are among those featured here.

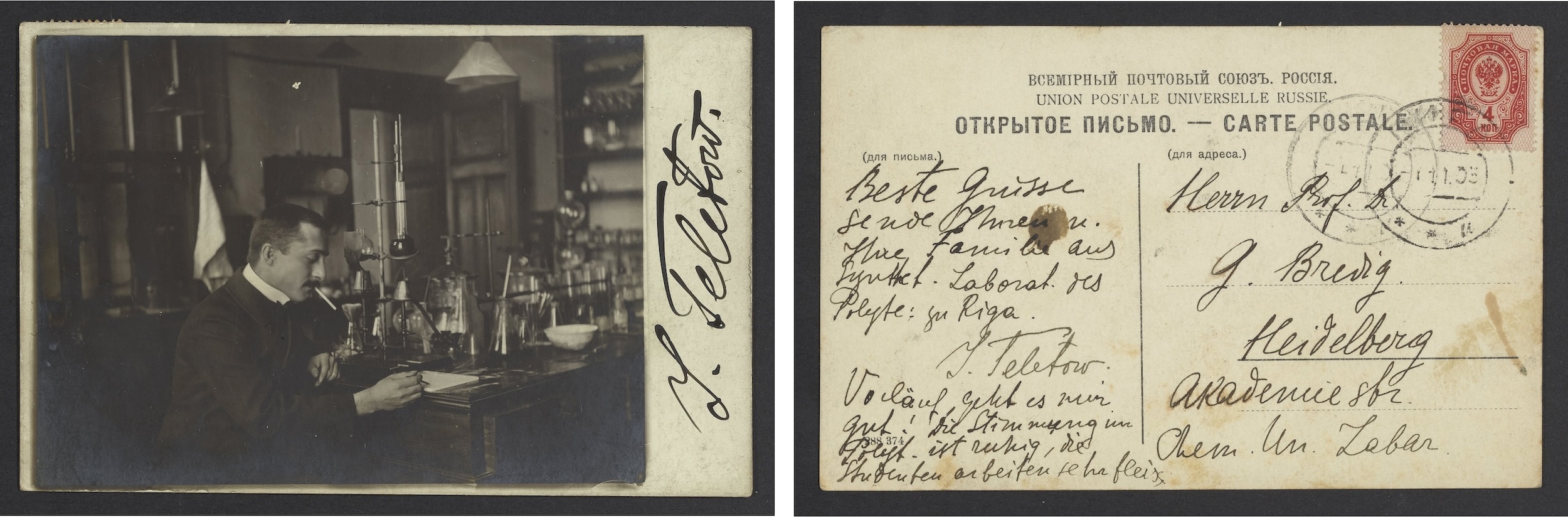

Back when one could smoke in the lab, the Ukrainian physical chemist Ivan Teletow sent Bredig an autographed photo of himself doing just that. Writing from the Synthetic Laboratory at the Riga Polytechnic Institute (in present-day Latvia) around 1905, Teletow shares that he is “doing well for the time being.” He notes that the atmosphere at the Institute is “very quiet” and that the “students work hard.”

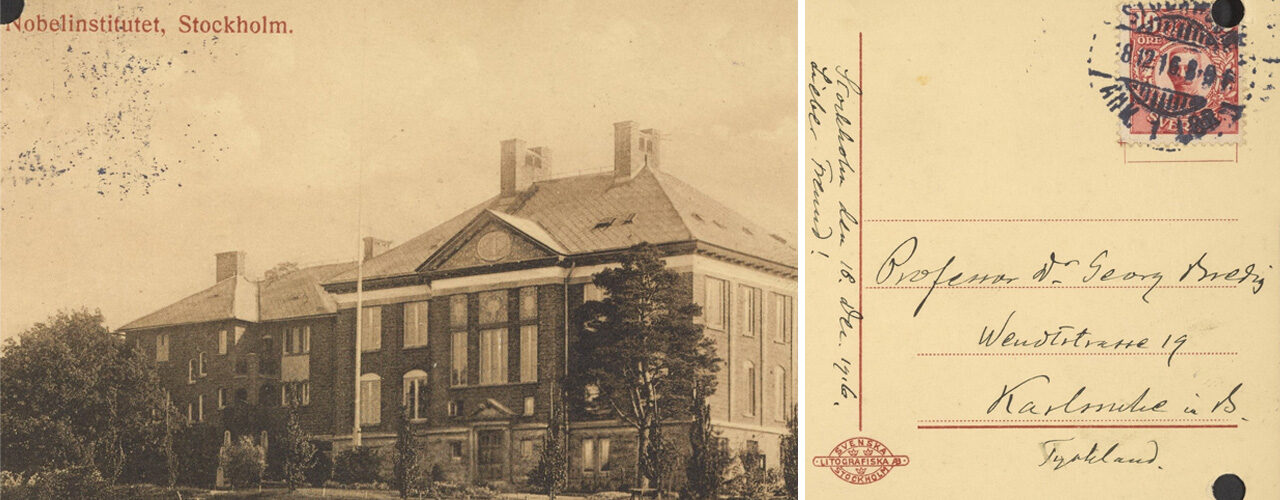

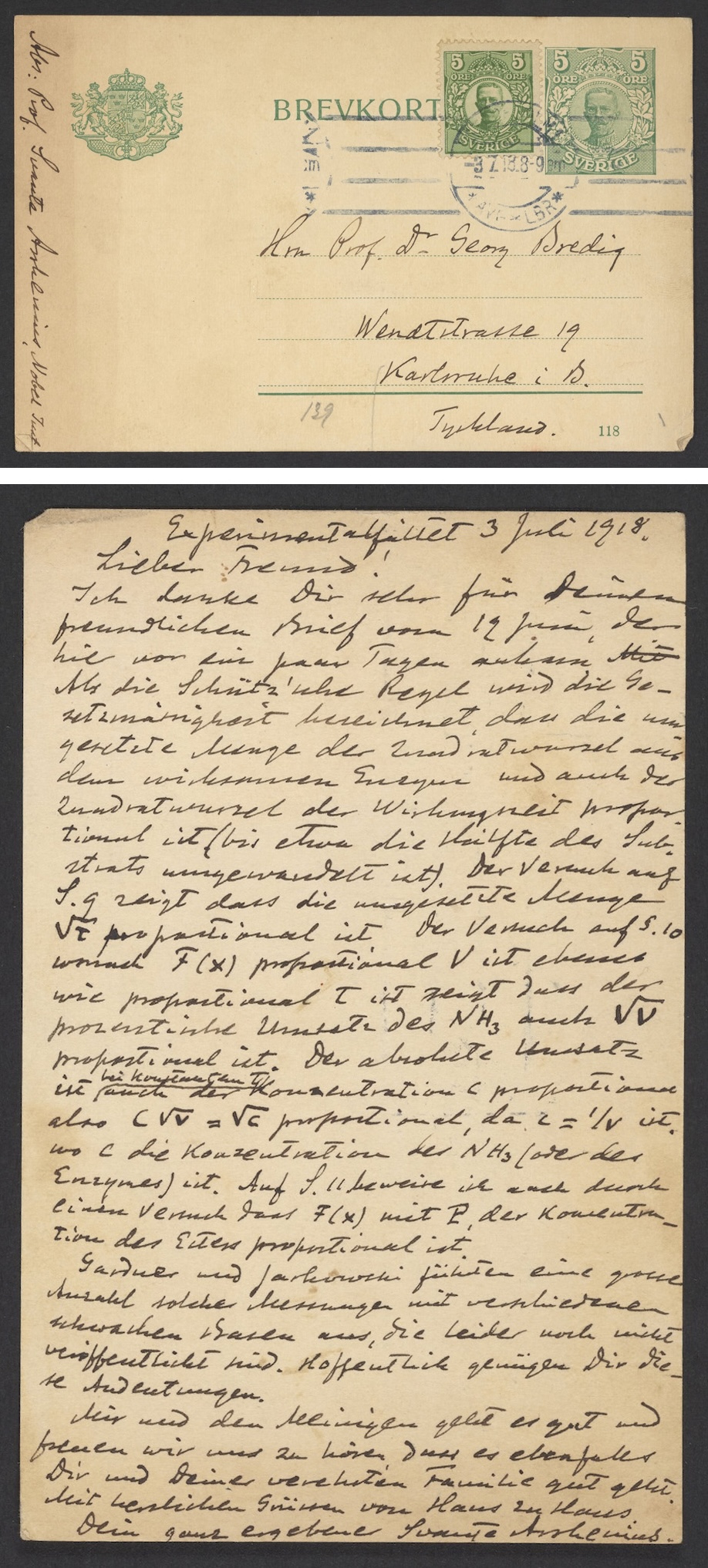

Nobel laureate Svante Arrhenius sent this unadorned postcard to Georg Bredig in Germany in July 1918. Writing from Stockholm’s new Nobel Institute for Physical Research, Arrhenius shared his calculations for an experiment with gases. He added that two other chemists produced similar measurements, but their results hadn’t been published yet. Arrhenius notes, “I hope these hints are sufficient enough for you” and sends “warm regards from our home to yours.” This is one of many letters and postcards exchanged between the two in the midst of World War I—a topic they also discussed.

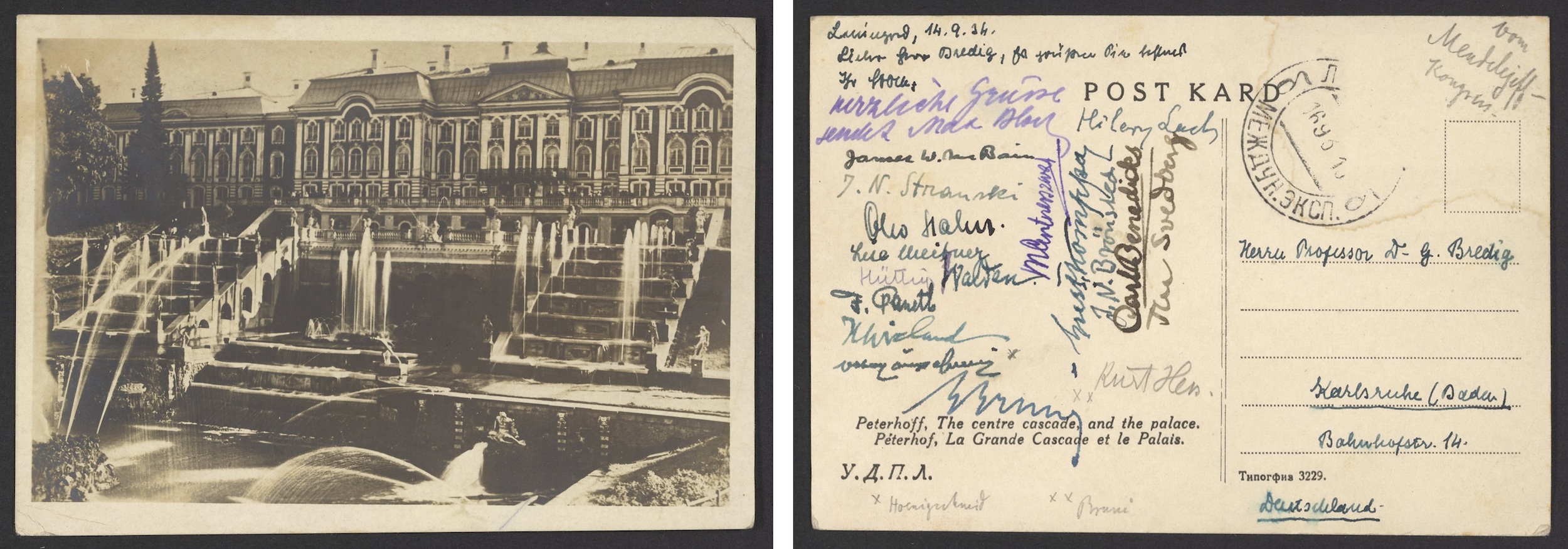

At the Mendeleev Congress that took place in Leningrad (today, St. Petersburg, Russia) in 1934, more than a dozen conference attendees signed a postcard and sent it to Georg Bredig. The changing political climate would have made it precarious or impossible for Bredig to travel. The signatories here include Austrian physicist Lise Meitner, German chemist Otto Hahn, and other colleagues and former students. The sepia photo on the front features the Grade Cascade fountain and Peterhof Palace, sharing some of the local beauty with the scientists’ absent friend and colleague.

These postcards written before Bredig fled his German home allow us to restore his personality and humanity. They capture his sense of humor and love for his family and friends. We also get an intimate view into his elite scientific network that spanned across Europe and included several Nobel laureates. Both the handwritten text and the images on the postcards intermingle personal with professional, demonstrating that such boundaries are permeable.

The lesson here is that historians cannot grasp the full technical history of science without also seeking to understand the scientist and their circle. While the Institute’s 19th- and 20th-century archives are flush with paper correspondence files, our 21st-century scientific correspondence will primarily be digital. Thankfully our archival team is now able to preserve emails for future historians. However, I do hope we’ll continue to see postcard collections as we save the papers of future scientists and engineers. Based on the abundance of affordable and vibrant choices in tourist shops today, postcards do still seem to have a future despite access to digital technology.

Featured image: Postcard from Svante Arrhenius to Georg Bredig featuring an image of the Nobel Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, December 1916.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Explore the history of science behind U.S. efforts to feed schoolchildren with Lunchtime exhibition curator Jesse Smith.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.