Buttons, Buttons Everywhere, and Not a Thing to Touch

On the goals and utilities of museum handling collections.

On the goals and utilities of museum handling collections.

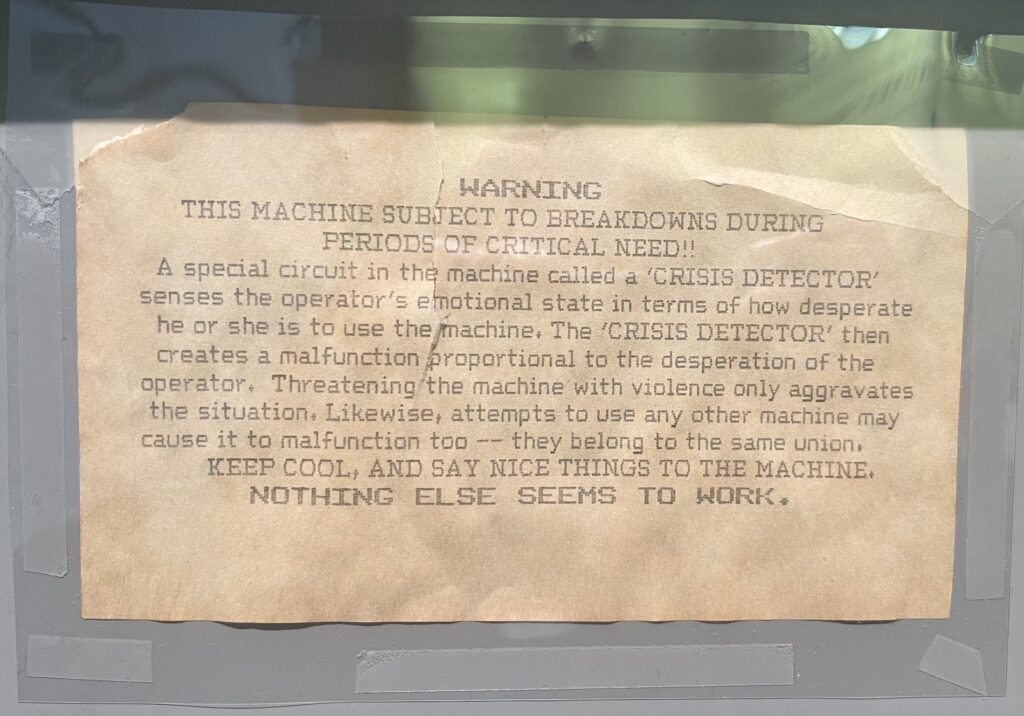

At the Science History Institute, we know it’s tempting to walk into our gallery and want to touch things—especially because so many of our most popular objects are covered in buttons, switches, and knobs that are just begging you to live out your mad-scientist dreams. Yet like most museums, we ask visitors not to touch the items on display. Many are old and fragile, which makes them more likely to break and harder to repair if they do.

You can’t exactly pop down to the hardware store and buy new parts for a 62-year-old machine made by a now-defunct manufacturer. Some of our machines, like the Varian A-60 nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer (pictured at top), are both physically and emotionally fragile.

But at least once a week, we bring artifacts into the museum that we enthusiastically want visitors to touch. More than 300 of our artifacts are designated as part of our handling collection. Visitors can touch these historic objects, use them, get a closer look at fine details, and generally become more familiar with them through hands-on engagement.

Today, I’ll introduce you to five handling collection objects related to dyes and textiles, the topic of our BOLD: Color from Test Tube to Textile exhibition.

This wool is one of my own contributions to our collection. Last year, I was developing an activity that revolved around wool. Wool has several unique material properties that make it water-resistant, including a coating of lanolin—a natural grease produced by sheep. Most of the soaps used to clean both raw wool and finished sweaters are designed to remove grease for a more effective wash, so it takes careful handwashing to preserve the lanolin. For most people, the extra effort isn’t worth it, so lanolin is usually removed when wool is processed for the convenience of both the manufacturer and the consumer.

Historically, however, lanolin has been very useful for people who live and work in cold, wet climates, especially before the invention of synthetic textiles. Fishermen are a famous example; lanolin-rich sweaters are perfect for people who work at sea and want the beneficial warmth of wool without being thoroughly soaked. I hunted for wool or yarn that still had lanolin to try and bring this history into the Science History Institute Museum. On vacation in Ireland, I stopped to visit the Sheep and Wool Centre in Connemara and asked a staff member if he knew where I might find some.

“How much room do you have in your suitcase?,” he asked.

Many types of sheep are primarily bred for meat rather than wool, and the quality of wool they produce is too low for commercial clothing. But sheep still need to be sheared for their own health, so the Sheep and Wool Centre had a shed of low-value wool from their small flock. I came home with three bags’ full, washed some of it, and documented two samples to add to our handling collection—one “raw” and one “scoured” (the first stage of cleaning).

Wool is cheap and plentiful, and while you’re not likely to find chunks of it in a display case, visitors now can feel it, smell it, and compare different steps in the processing cycle of wool. This is also a great opportunity to talk about what counts as “the history of science.” Many visitors walk into our museum expecting to see the groundbreaking, game-changing examples of scientific technology from years past—and to be fair, we do have a lot of it! But ordinary objects are the product of technical knowledge and historical change, too. Even the humblest bit of fluff can teach us something about the past and present.

Other objects included in our handling activities were purchased new. We tend to think of museum objects as old; haven’t you ever felt old when you spot an object from your lifetime on display? But of course, everything happening right now will be history at some point. In some cases, it is easier to acquire things when they are new, such as our loom and spindle.

This is not exactly new technology. If a museum curator wanted to acquire a loom that was 2,000 years old, they probably could—as long as they were prepared to spend a significant chunk of the collections budget. Contemporary versions are a bargain and allow visitors to experience textile manufacturing themselves.

A spindle is used to make thread. The raw material—in this case, wool—is drawn taut and thin using the hook on one end, then spun to strengthen and lock it into its new shape. The thread is wrapped around the spindle until it’s full. Two or more threads can be plied, or twisted together, to form stronger, thicker threads or yarn. When it comes time to weave, warp (vertical) threads are strung through the notches on the frame of a loom. Weft (horizontal) threads are wrapped around a tool called a shuttle that can be pushed through the threads. Our loom also includes a heddle bar, which has two sets of notches at different heights so the warp threads can be automatically positioned higher or lower.

It may sound simple but when visitors try to use these objects, they often discover that it takes more time and patience than they expected. A steady hand is needed to pass the shuttle through the threads without bumping them. If the weft is too tight, it can pull the warp out of alignment. Too loose, and you are left with awkward loops on the edge of your fabric.

As for spinning, it takes lots of practice to get the tension correct. Most of the thread on our spindle was made by one museum guide who developed a knack for it and a visitor who already knew how to spin. Everyone else who has tried (including yours truly!) has given up.

We often pair these objects with videos of the 18th-centry inventions that led to the Industrial Revolution. Even if you already know that machines make your clothing today, it can be galling to spend 45 seconds carefully weaving a single row, only to watch a flying shuttle make the same journey in the blink of an eye. The skill it took to craft clothes by hand and the scale of the disruption caused by the industrial takeover suddenly becomes much more apparent.

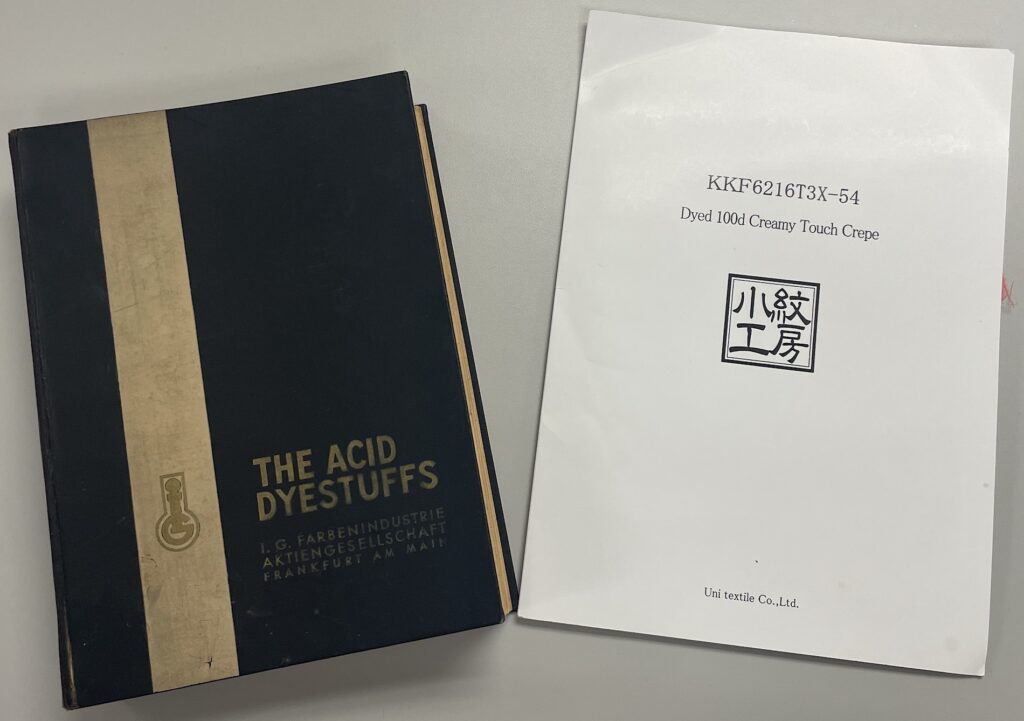

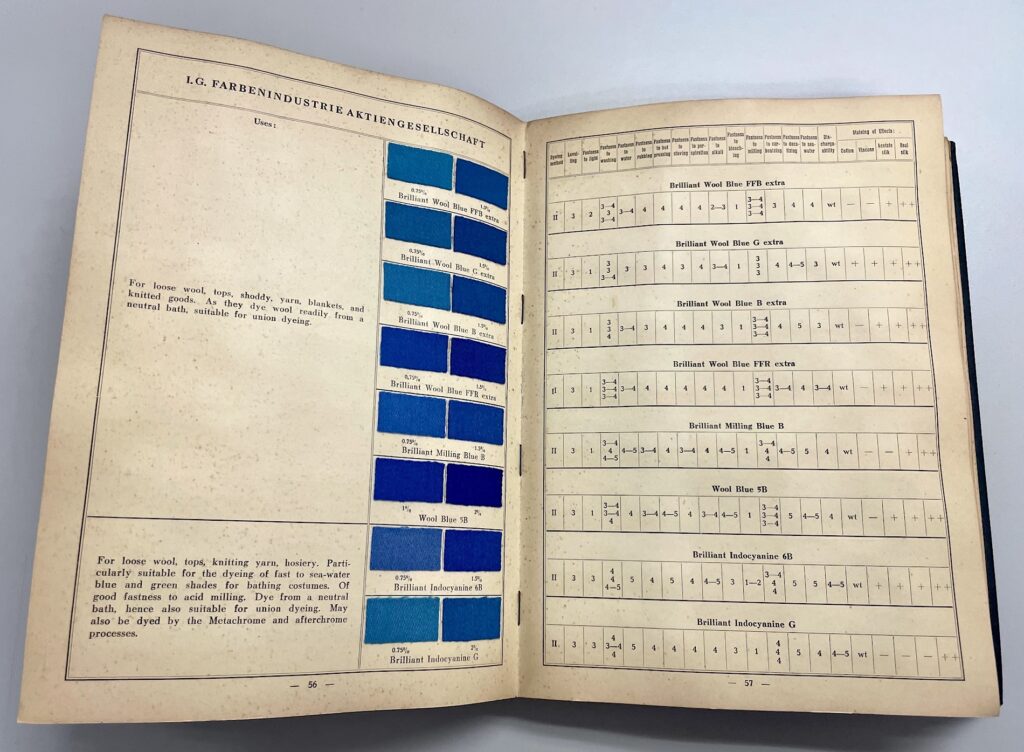

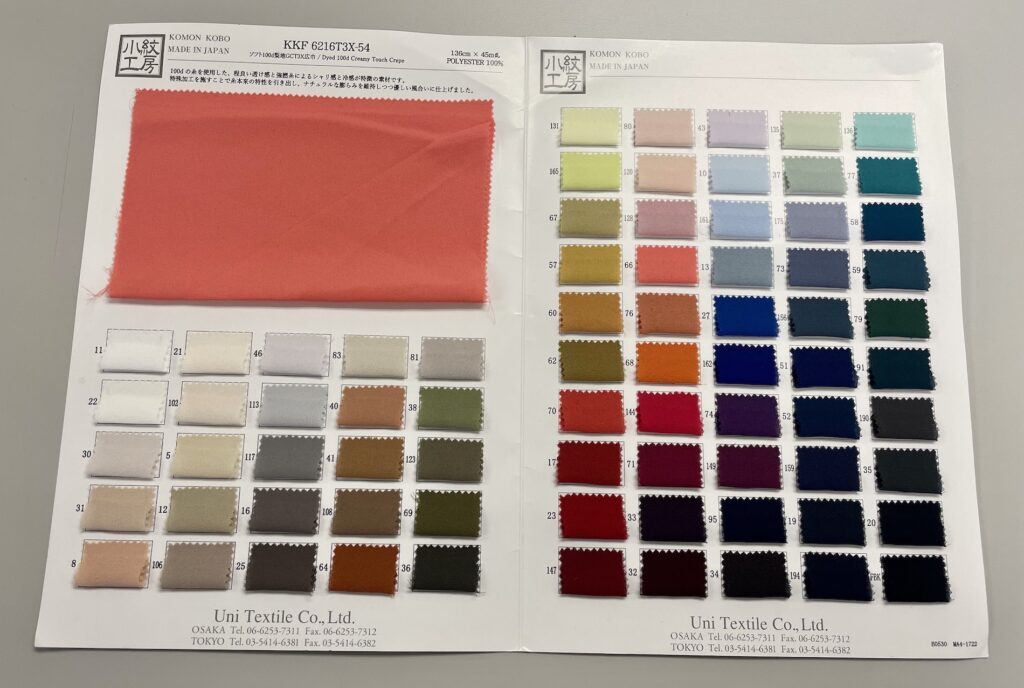

Our last two objects are dye sample books, produced for the same purpose almost a century apart. Dyehouses and fabric manufacturers produce books that contain small samples of dyed cloth to show the range of their products. These samplers are then shipped to fashion designers and other clients who want to know the precise colors available to them.

Unlike a classic work of literature, a dye book tends to have a short life. Most have probably been thrown away, just as you might throw away a clothing store’s catalog (or delete their emails). At the Science History Institute, however, many examples of “grey literature” like this are preserved in our library. If they don’t circulate and the library wants to make space for books that are more useful to researchers, they might pass them on to our handling collection.

That is what happened to the first book, which is from the 1930s. Visitors are often surprised to learn about the age of this book; one recent visitor even asked if it was authentic or a recreation made by the museum. Unlike a novel, which is read for hours at a time on multiple occasions, this sample book has probably spent most of its life closed on a bookshelf, safe from light and rough handling, which has kept it in great shape. By rotating this object with others from our collection, we can prolong its life without locking it away from the public entirely.

Finally, we have a modern dye sample booklet, which also followed a roundabout path into our collection. It was originally donated to FabScrap, a nonprofit that recycles scraps from clothing companies, including their old samples. Rather than toss this fabric into a landfill, producers can send it to FabScrap, where it is recycled into insulation or furniture stuffing—or, in this case, into a museum object!

Exploring the visual differences between these two books is a compelling way to engage visitors in a discussion of how the fashion industry has changed over the last century. The 2020s booklet is more disposable, contains synthetic fabric, and is international in origin—all themes that our museum also explores in our BOLD exhibition and in our Dyes & Textiles Tour.

If you would like to take the tour or explore more of our handling collection—which also covers topics such as food science, microscopes, and science toys—you can check our events calendar or search our collections.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.