A Synthetic History

From the lab to the closet, nylon spins a useful web.

From the lab to the closet, nylon spins a useful web.

What if we’d never invented nylon? Could Apollo 11 astronauts have walked the moon? Likely not. Space suits are made of synthetic polymers, nylon, and spandex. So are stockings, lingerie, athletic wear, and evening gowns. Such scientifically developed materials originated in the 20th century at key chemical manufacturing companies like DuPont, Dow, Rohm & Haas, and Gore-Tex.

My musings about nylon are just one of the pleasures of working in a history of science museum and library. When I explore our collections, I often find myself asking, “What if?” As I discover the history behind nylon dresses, Bakelite phones, drones, synthetic arteries, and quirky NMR machines, I realize that for most everything we use today, chemistry played the starring role. And the history behind that chemistry matters: knowledge about the past is integral to understanding the present.

Visitors to our museum might be surprised to find a blue nylon dress by the fashion designer Emma Domb on display. What does that draped and gathered evening gown have to do with the past and present of chemistry, or for that matter, the synthetic arteries and veins exhibited nearby? A lot, as it turns out. Textiles are science, and the relationship between science, agriculture, textile manufacturing, and color is extensively documented in the Institute’s collections and in two of our recent exhibitions, BOLD: Color from Test Tube to Textile and The Story of Ramie: From Seed to Finished Garment.

Years of scientific research by chemists, physicists, and chemical engineers went into the development of nylon—a versatile synthetic silk born from a chemical soup of coal, air, and water—and successor synthetics such as Dacron and Gore-Tex.

Nylon was in fact the second successful attempt at man-made silk. Rayon came first; before that, there were a number of silk-alternative failures. These include François Xavier Bon de Saint Hilaire’s 1709 superfine spider silk stockings, a gift to King Louis XIV. I imagine Bon’s test silk production lab was so filled with netted glass jars of crawling spiders and buzzing flies that friends declined to stop by. According to Nicola Twilley’s New Yorker article, Bon reported that the project was fatally complicated by spiders eating fellow members of the production team. There is no record of whether the Sun King actually wore the infamous spider socks.

You can source facts about spider silk, rayon, and other fascinating silk alternatives by checking out the Institute’s Othmer Library copy of Joseph Leeming’s little blue book, Rayon, The First Man-made Fiber (1950). If you can’t get to our library, the book is accessible online. The story of spider silk cloth production in the 1700s is yet another reason for keeping research libraries around.

With respect to rayon, Leeming explains that in the late 19th century, experimenters learned that “cellulose, when treated with caustic soda to swell the fiber, and then treated with carbon bisulfide . . . converted an entirely new compound.” When that compound was dissolved in water, a viscous pink-red slurry resulted. The slurry, called “viscose,” was shaped into objects such as handles and pulls, but it made for a brittle fiber and attempts to spin it failed. In time manufacturers learned that the slurry needed aging before it could be spun into flexible and strong fibers. By 1910 two million pounds of rayon were being made in Great Britain per year.

What was the most popular rayon product? Stockings, of course—now much more affordable than their silk counterparts. There were other benefits: silk yellows and browns over time, but rayon ages without discoloring.

My mother’s 1956 wedding dress—which I wore to my 1986 wedding and my daughter-in-law, Marina Cooke, also wore in 2023—is made of rayon. At 68 years old, the dress is still strong, beautiful, and creamy white in color. The rayon satin has a luster and a weight that makes for a lovely dress.

Let us now put rayon in the rearview mirror and move on to nylon, the star of this blog post.

Invented by DuPont in 1938, nylon is made of two chemical intermediates: adipic acid and hexamethylenediamine. It can be manufactured, stockpiled, and stored as chips. The textile manufacturing process DuPont developed first heated this raw material, then protectively blanketed it with an inert gas that was a high-quality grade of nitrogen, and finally squeezed it through a spinneret under high pressure. The emerging fiber was then wound into rolls at a rapid rate of 2,500 feet per minute.

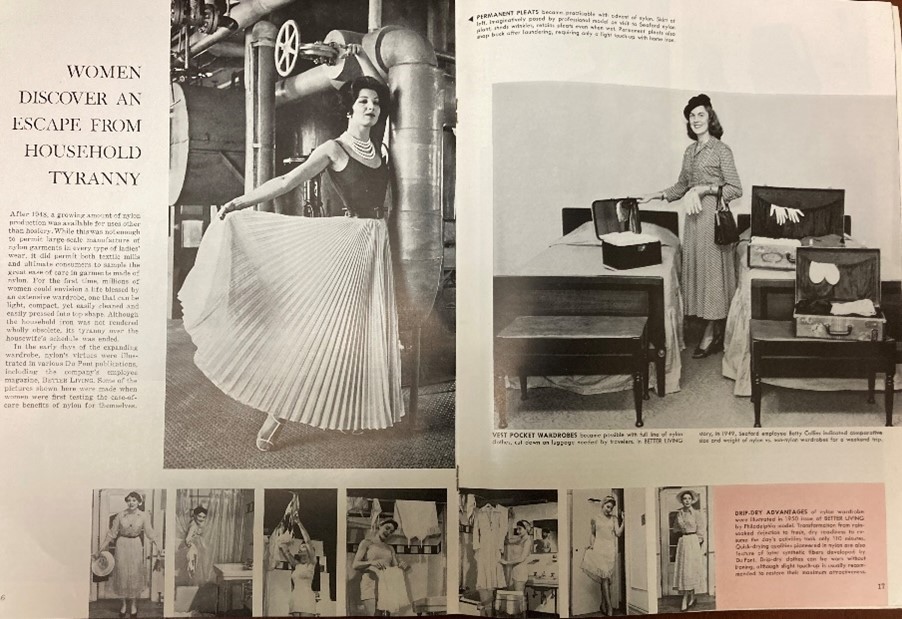

Nylon was originally used in such military applications as parachutes and ropes, but after World War II, it became available for luxury use, improving on rayon and replacing silk in women’s hosiery, Paris couture dresses, and premium textiles. It was in abundant supply and much less delicate than silk.

In fact, nylon is so colorfast and durable that you, too, can own a dress that belongs in a museum! Domb, the designer of the Institute’s blue dress, was inspired by Dior’s New Look, and made elegant and affordable nylon evening gowns so popular that she won a 10-year contract to supply the Miss America pageant. Her cocktail and evening gowns are still abundantly available as vintage fashion purchases on Etsy and eBay.

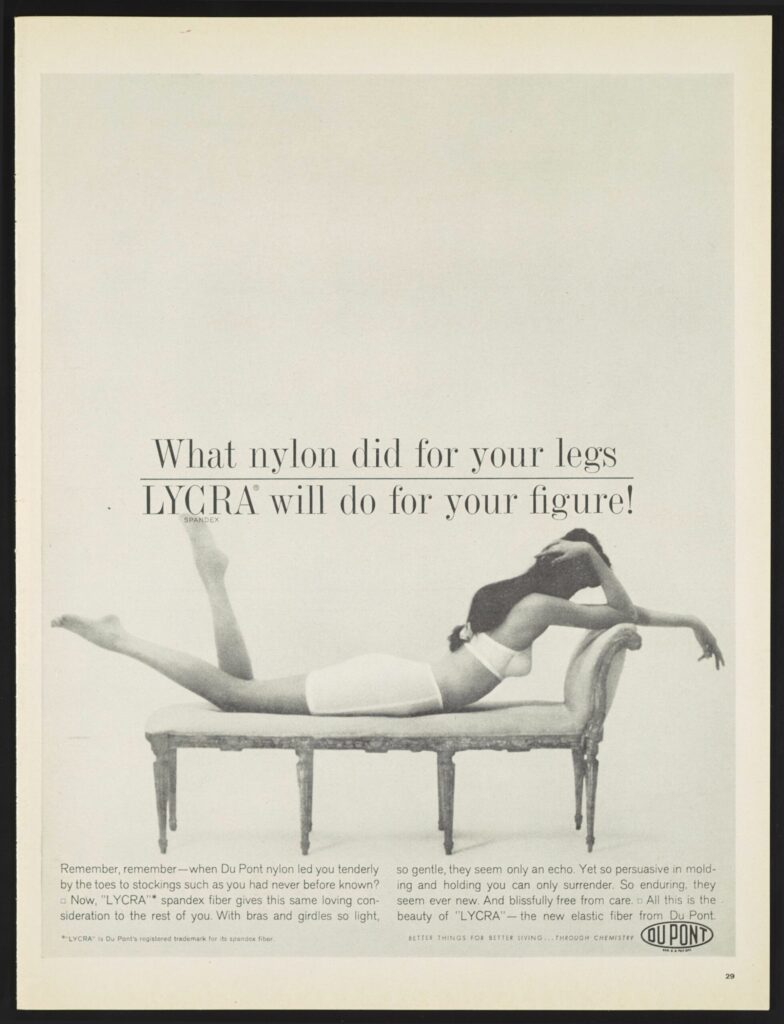

In 1958 things got even better with the development of Lycra, a DuPont polyurethane fiber product invented by Joseph Shivers. The company launched an advertising campaign featuring Lycra’s innovative shapewear with the slogan, “What nylon did for your legs, LYCRA will do for your figure.”

Today’s wardrobes would be impossible without the research and development done by chemical companies. Pre-industrial dye fixers like urea and ammonia from urine have been replaced by man-made chemical solutions, and itchy, hard-to-dry wool knit textiles used in bathing suits have been gratefully exchanged for nylon, Lycra, spandex, and elastane. There is quite a lot of chemistry in our swimsuits today, not to mention in our yoga pants, sneakers, outerwear, and vegan synthetic leather.

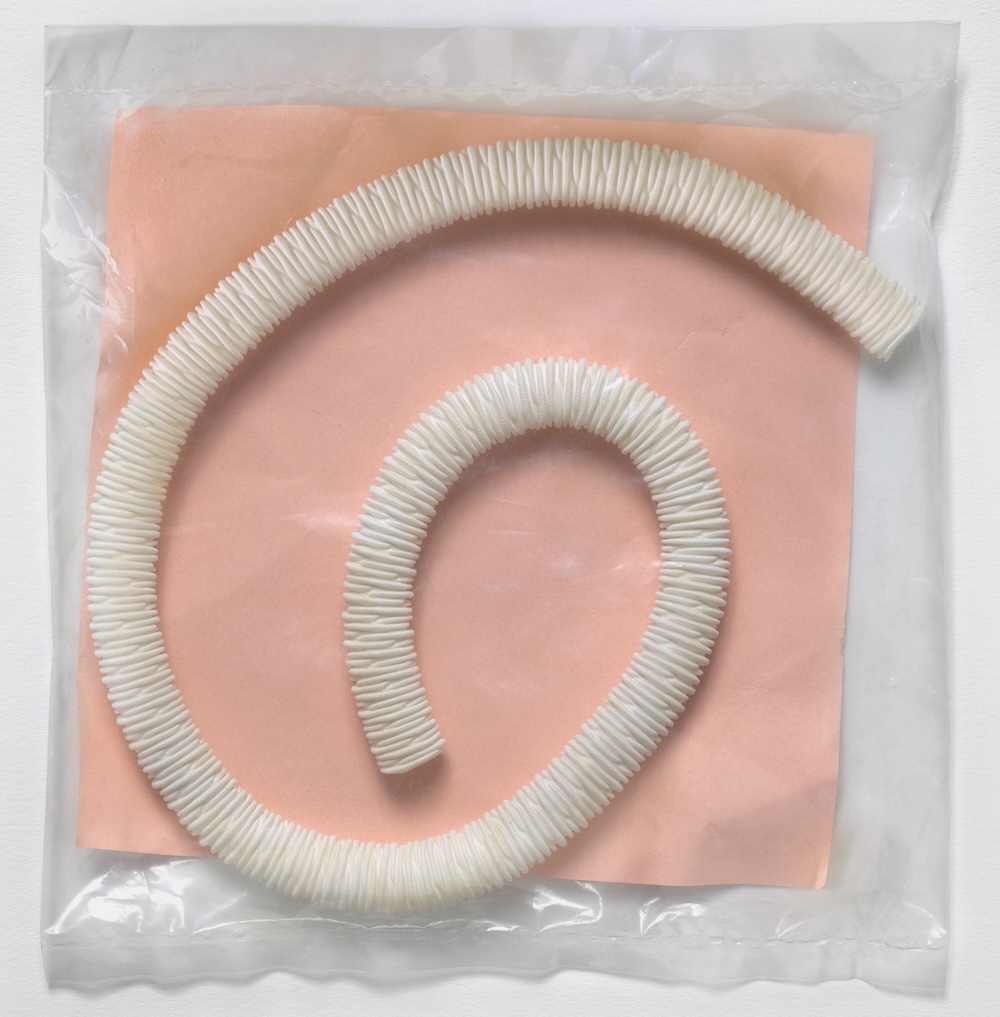

Despite being perfect for parachutes, rope, and dresses, nylon was not a sound choice for artificial veins. Instead, its success sparked research that led to hypoallergenic, nonabsorbent materials that could be used for synthetic veins and arteries.

One of these was Dacron, a DuPont polyester product made of polyethylene terephthalate that was launched in 1951. When Michael E. DeBakey—a doctor who specialized in the repair of aneurysms—was looking for a human tissue substitute, he made an over-the-counter purchase of Dacron, tested it as a synthetic artery, and found that it worked.

The DeBakey knitted arterial graft made of Dacron went on the market in 1958. That same year, chemist Wilbert Gore left DuPont to develop a new material in his basement with his wife Genevieve: expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE). A porous, flexible material, ePTFE has been used in Apollo space suits, medical devices, footwear, gloves, and outerwear. Gore’s textile research underpins the Gore-Tex brand.

There’s lot more to see and learn about nylon in our collections. Check out this list of museum objects related to nylon. We have several items connected to Joseph Labovsky‘s work at DuPont, including a pair of employee wear test nylons from a former DuPont employee (yes, they arrived clean!). The Othmer Library has many resources on nylon and other artificial fibers, including a DuPont publication titled Nylon: The First 25 Years. You can also explore our digital exhibition, Nylon: From Labs to Legs, read more about nylon and synthetic fibers in Distillations magazine, and listen to a podcast exploring “The Yoga Pant Problem.”

These are all great examples of the surprising role chemistry plays in shaping our daily life—and our legs. We live in a modern age of easy-care clothing because scientists set out to solve the problem of overly expensive silk . . . and uncooperative, cannibalistic spiders.

Thank you to public services librarian Phil Bellizzi and Molly Sampson, head of collections management and registration, for their help with research for this post.

Featured image: View of the Spinning Elements display from our permanent exhibition featuring a blue nylon dress.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.