A Pigeon, a Cow, and a Book Detective

Investigating the origins of two early-20th-century Italian “flap anatomy” books.

Investigating the origins of two early-20th-century Italian “flap anatomy” books.

As a library cataloger, my job is creating the descriptions of library materials you find when you search our library catalog for an author, title, or topic. I find this work inherently interesting since I get to learn a little bit about a lot of subjects, and I see all the new books that come into our collection.

However, there often isn’t much mystery involved. After all, books—particularly contemporary ones—are self-presenting documents: the title give us a sense of the book’s subject, an introduction or summary on the book jacket tells us more, an author’s photograph and biography provide context about the creator, and so on.

But every so often, a bibliographic mystery crosses my desk, and I get to indulge in some detective work—in this case, to make like Columbo about Il colombo.

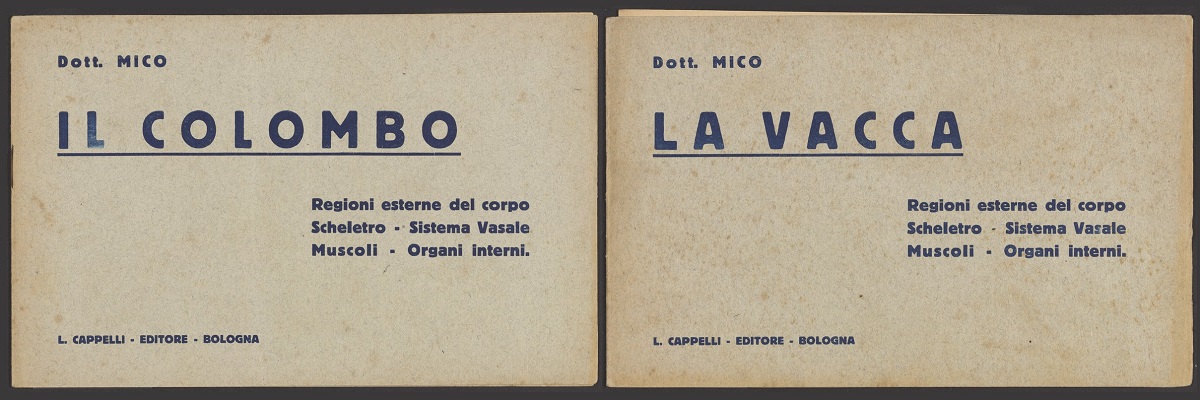

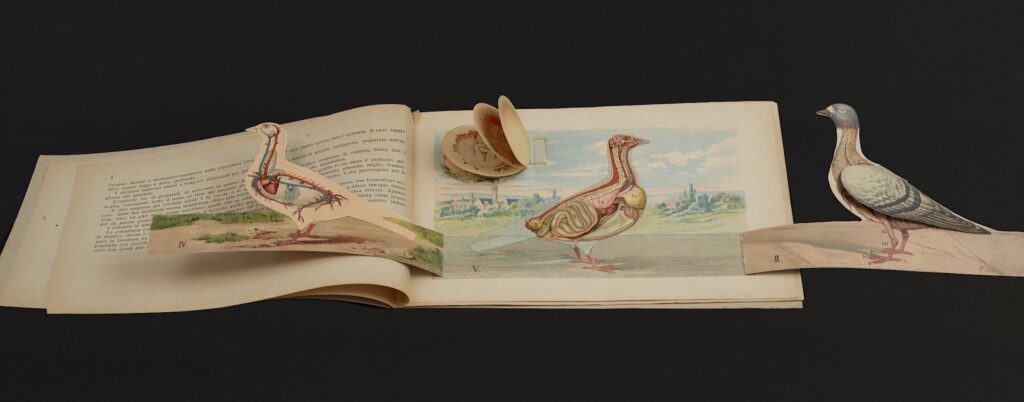

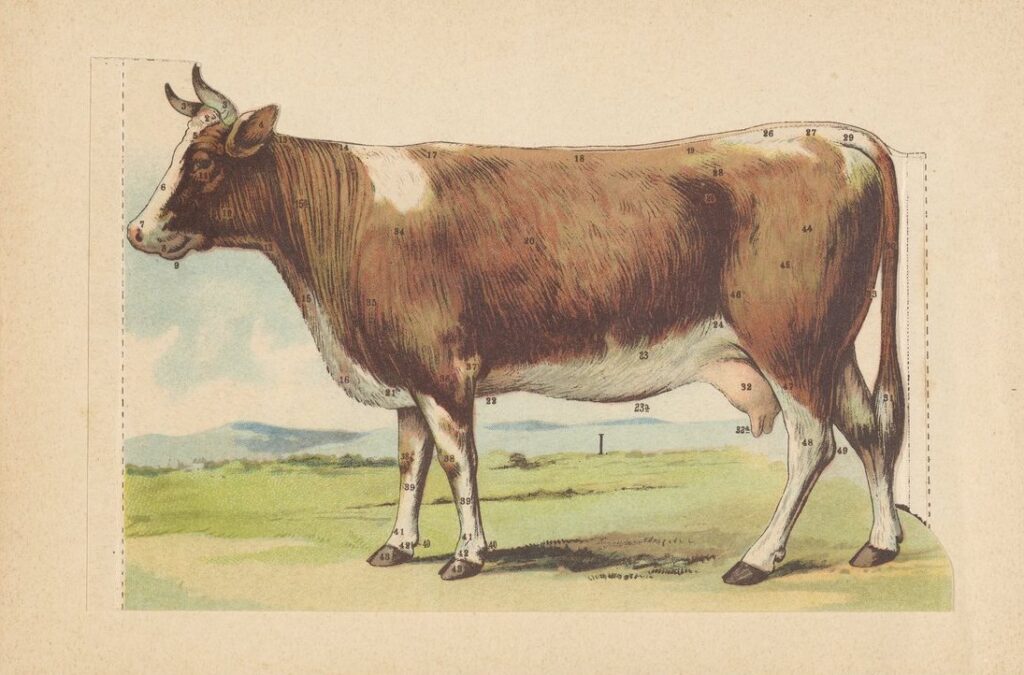

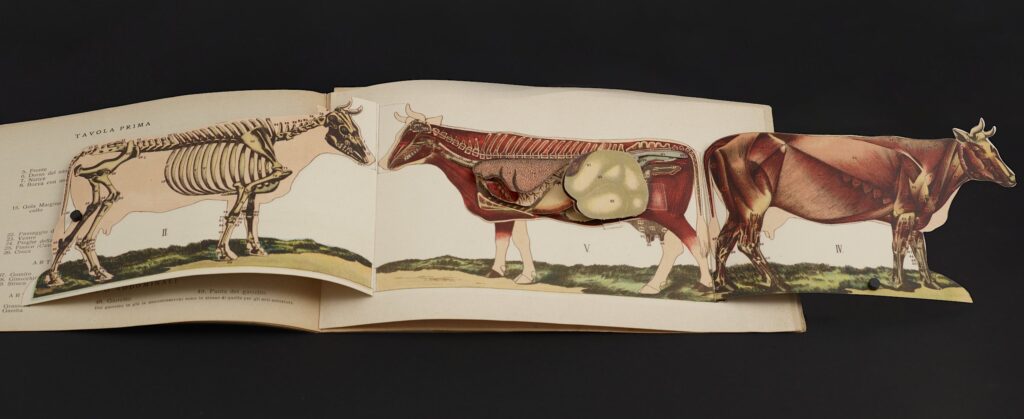

Il colombo (The Pigeon) and a second work, La vacca (The Cow), are early-20th-century Italian “lift-the-flap” books that we purchased for the Institute’s library collection at the Philadelphia Rare Book Fair.

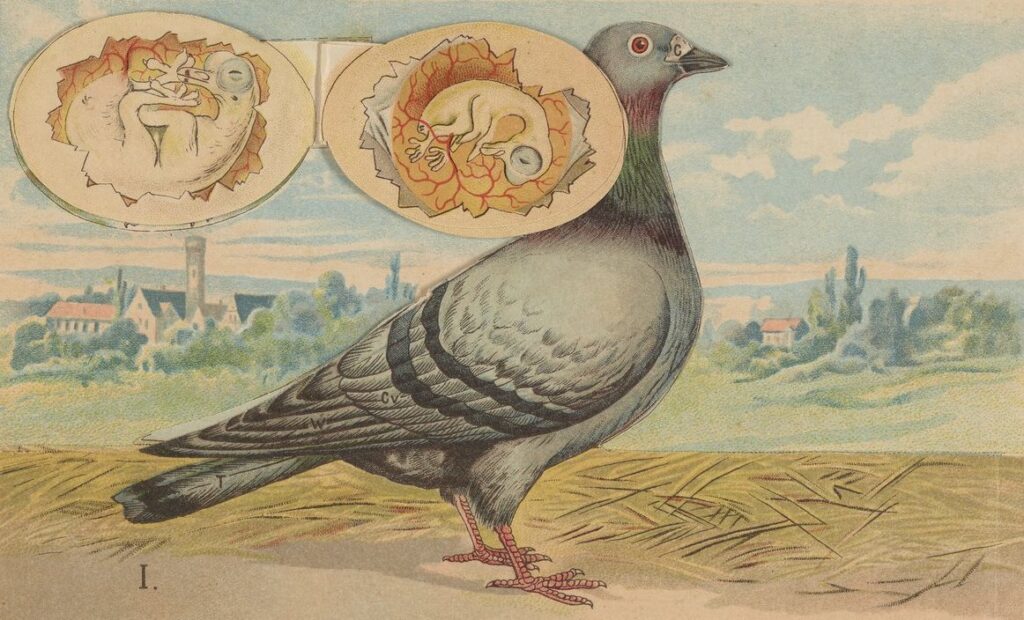

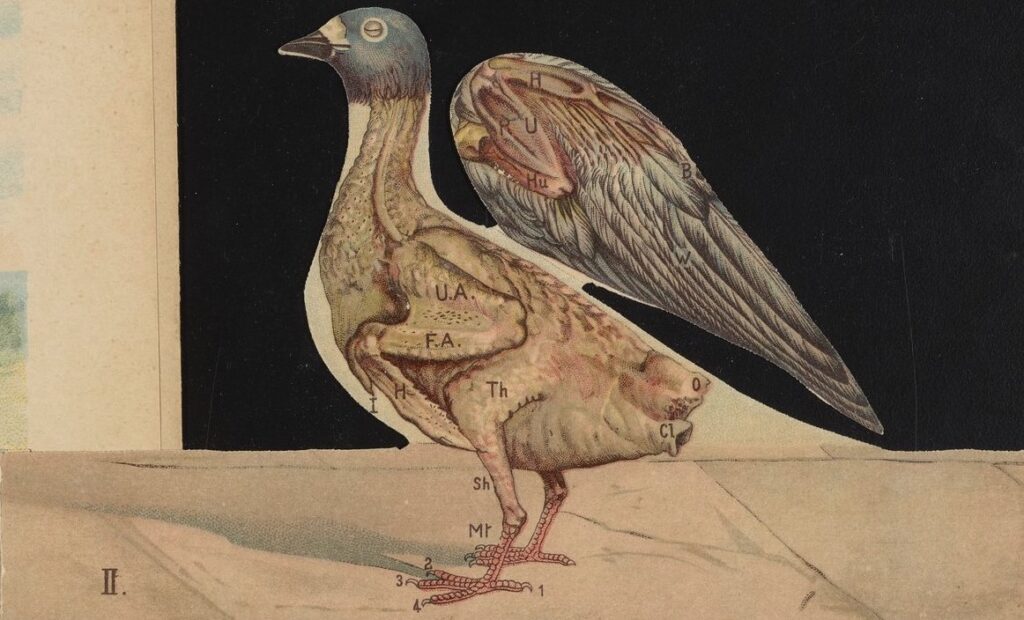

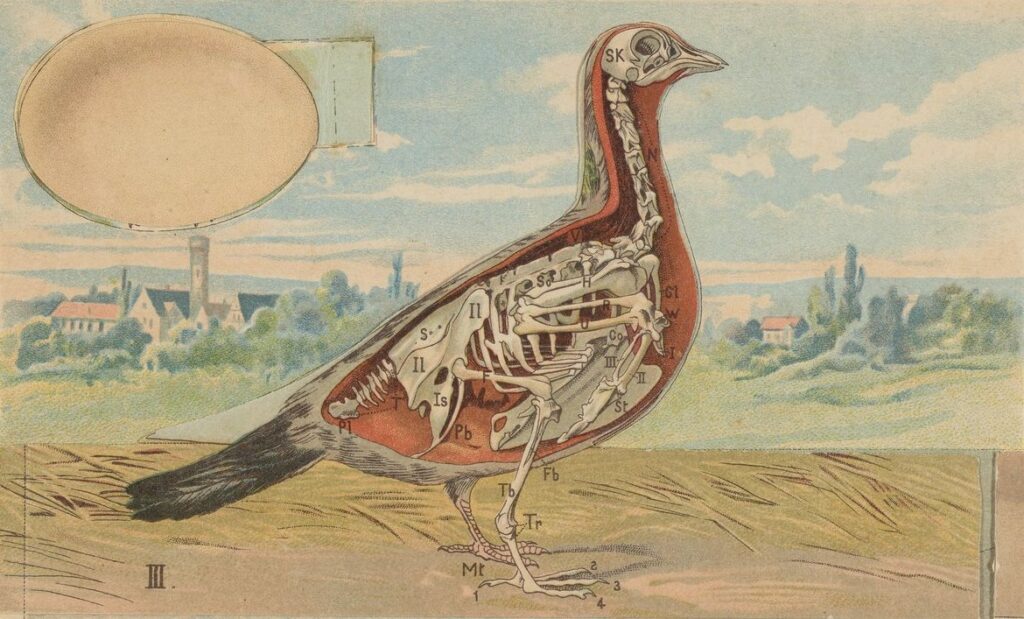

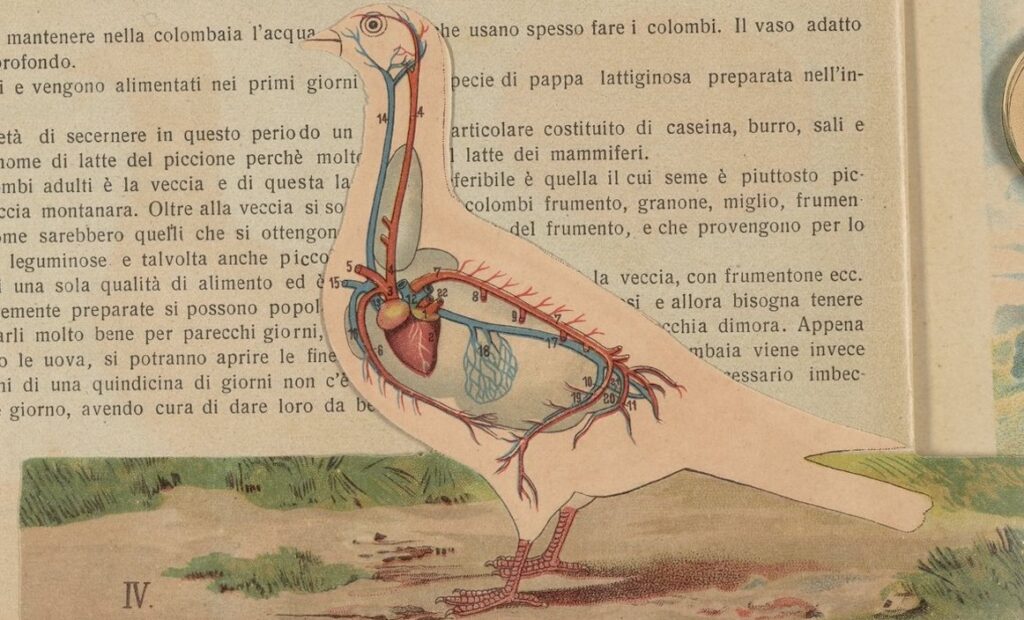

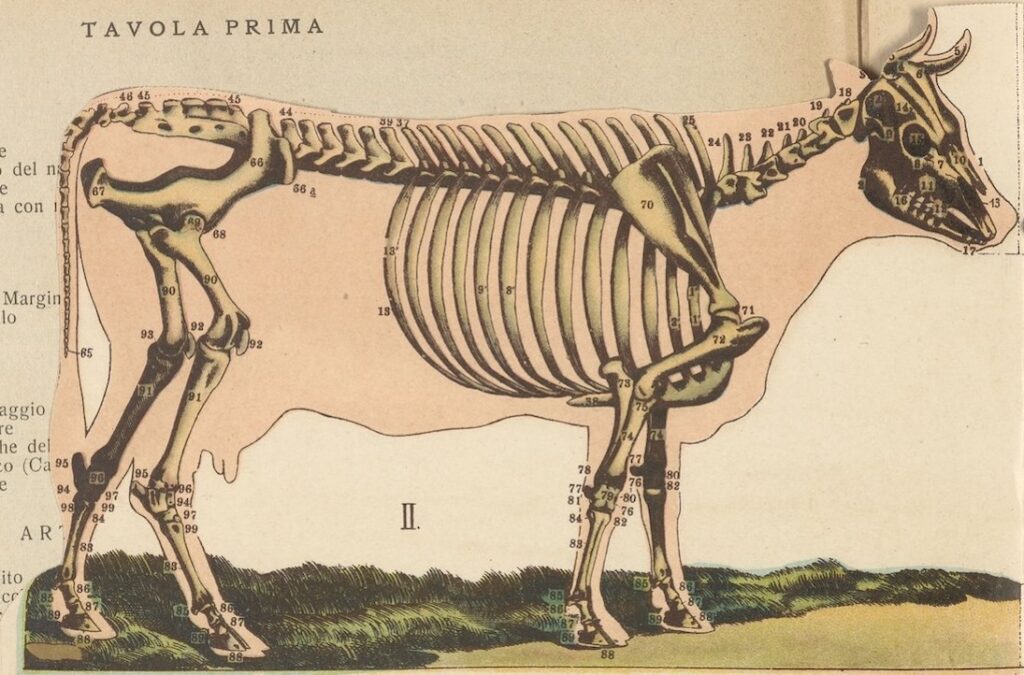

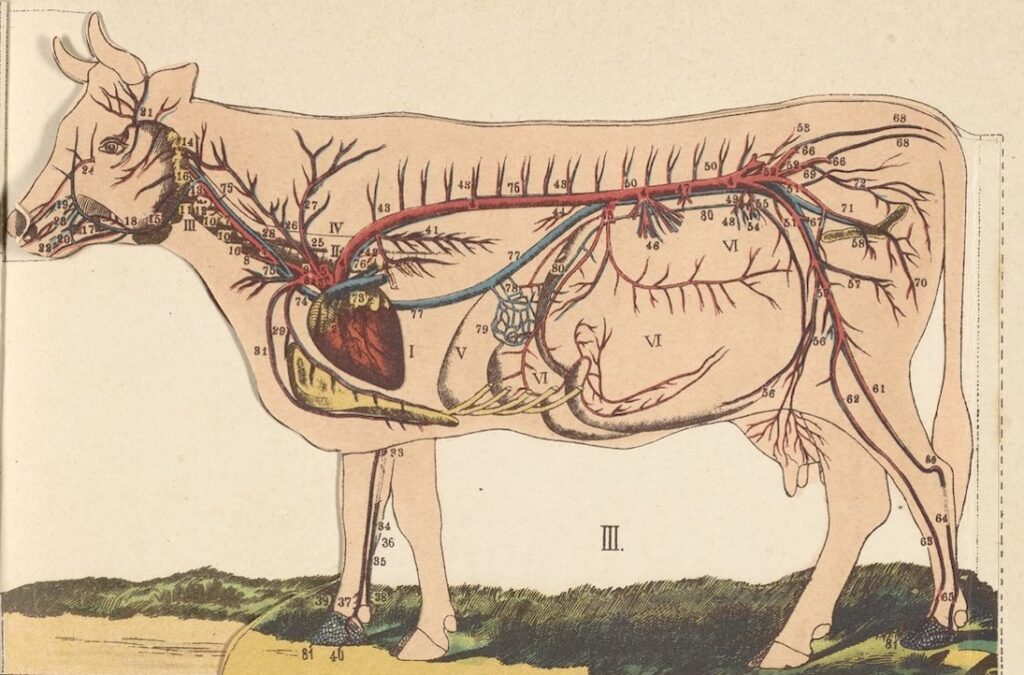

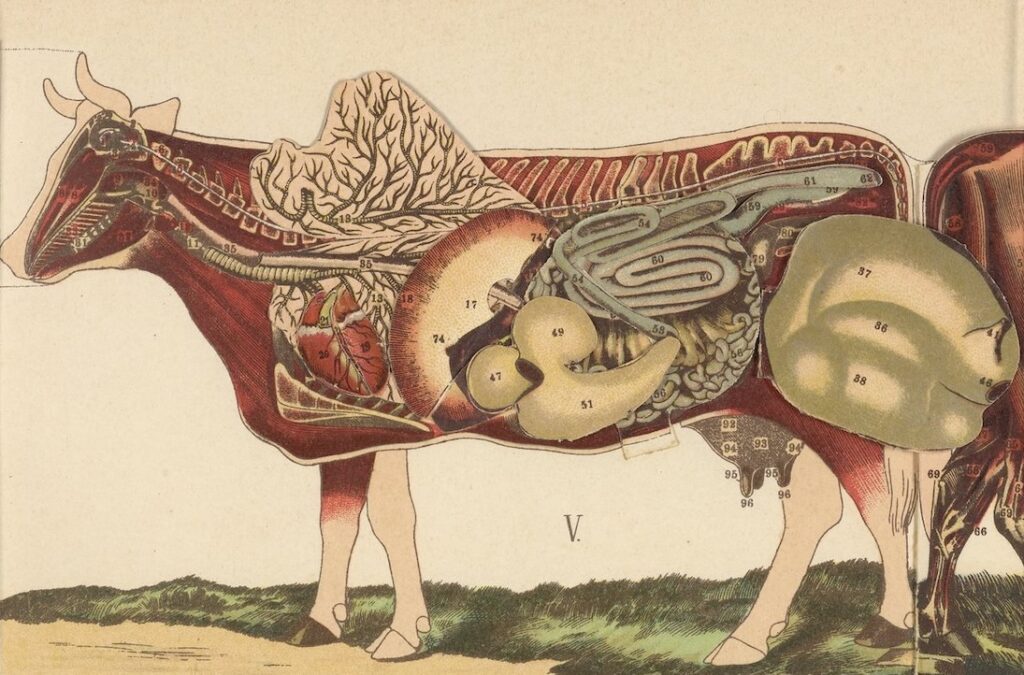

They are visually splendid works. The reader lifts flaps of detailed colored illustrations to travel from the outer bodies of a smiling cow and a bright-eyed pigeon and her egg; through their skeletal, vascular, and muscular systems; and into the internal organs of each animal.

Pages from Il colombo.

But besides their obvious visual charm, we didn’t know much about these works. The cheerful illustrations and movable flaps are characteristic of children’s books, but the accompanying text offers practical animal husbandry advice that seems targeted at an older reader. Were these some sort of “Italian 4-H” publications or perhaps intended for veterinary students? What clues might the identity of the author “Dott. Mico” or information about the publisher “L. Cappelli” provide?

Pages from La vacca.

The rarity of these books is behind much of this mystery. I found four other libraries with copies, all in Italy. The books were published around 1924 by Cappelli Editore, a Bologna-based publishing house established in 1913 by Licinus Cappelli. The firm flourished in the 1920s, in part due to cordial relations with Mussolini’s regime. Cappelli published a variety of genres, including popular and literary fiction, poetry, medicine, law, and women’s magazines.

I learned that Cappelli published three other similar works on animal husbandry in or around the same year as Il colombo and La vacca: Il cavallo malato (Diseases of the Horse), Il maiale (The Pig) and La capra (The Goat), all written by “Dott. Mico” (Dr. Mico). Mico remains a mystery, as these titles are the only works attributed to them in WorldCat.org or the Italian national libraries in Florence and Rome. The horse, pig, and goat volumes are even scarcer than the pigeon and cow: the only copies are at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze.

A review of all five books published in the January 3, 1926, issue of L’Italia vinicola ed agraria (Italian Viticulture and Agriculture) calls them a useful and practical novelty (“una utile e practica novita”). The books have “scant text,” but enough for understanding; they are, the reviewer writes, excellent works that contribute to the successful performance of “these subsidiary agricultural industries” (“sussidiarie industrie agricole”), by which presumably is meant breeding and rearing cows, pigeons, horses, pigs, and goats as working animals or for consumption.

The 1926 reviewer assumed an adult reader for these works—or at least someone old enough to be engaged in raising livestock and working animals. And although the reviewer found the “lift-the-flap” style of the books a novelty for adults, I learned there’s actually a long tradition of books that use movable elements—flaps, but also rotating discs, pull tabs, and pop ups—to explain scientific, technical, and medical concepts to non-specialist adults.

The earliest instance of movable elements in Western books are volvelles—paper or parchment constructions with a series of rotating discs that can be spun to calculate values or generate different combinations of letters and/or numbers. Volvelles were probably introduced to Europe from the Arabic world in the 12th or 13th century, where they were used in mathematical and astronomical works.

Many sources cite the work of Catalan philosopher Ramon Llull (1232–1316) as the first appearance of volvelles in Europe. For Llull, who sought to create a logical system that proved the truth of Christian theology, volvelles were used to generate combinations of letters that corresponded to theological principles. More commonly, volvelles were used for mathematical or astronomical calculations, as in our 17th-century edition of Johannes de Sacrobosco’s De Sphaera.

As printing became faster and cheaper in the centuries after the invention of the Gutenberg printing press, movable elements became increasingly common and diverse. (To see some different movable elements in action, check out this video from the Newberry Library.)

The earliest “flap anatomies” like those we see in La vacca and Il colombo date to 1538, when German printer Heinrich Vogtherr printed the first illustrations to represent human anatomy via a series of liftable flaps that mimicked anatomical dissection. An immediate success, Vogtherr’s illustrations prompted similar publications in France, Italy, the Netherlands, and England. As Madeleine Killacky explains, these “pop-up anatomies” were meant for non-specialist readers:

These texts can be considered rough summaries of university anatomical handbooks, but they were also elaborate, if crude, typographical artifacts designed for a popular audience. Most noticeably, the images dominate the text, which they sum up and simplify. Through these paper surrogates a non-specialist could, for the first time, delve into the furthest reaches of the human body.

First issued as stand-alone sheets called “fugitive sheets” for the ease with which they could be misplaced, flap anatomies were eventually incorporated into scientific, medical, and technical texts for adults.

Rotating discs, pop-up elements, liftable flaps, pull tabs, and other movable elements only became associated with—or in historian of science Kathleen Crowther’s harsher wording, “relegated to”—the domain of children after the mid-18th century, when children’s literature emerged as a genre. Crowther explains:

The charm and whimsy of pop-up books might seem far removed from the dry seriousness of technical literature. But the first three centuries of printing, from about 1450 to 1750, most pop-ups appeared in scientific books. Movable paper parts were once used to explain the movements of the moon, the five regular geometric solids, the connections between the eye and the brain, and more.

With this context, the juxtaposition of bright illustrations and liftable flaps—hallmarks of children’s books to our early-21st-century eyes—with pragmatic tips on how to visually appraise the health of a dairy cow’s udder or properly outfit your dovecote, is less bizarre. Our glorious cow and pigeon are, in fact, heirs to a long tradition of books that used movable elements to demystify scientific concepts.

One more thing: If this journey through the mystery of Il colombo and La vacca have piqued your interest in movable books, great resources for further reading include the Newberry Library’s movable books research guide and the Movable Book Society.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.