A Gray Matter

We’re still scratching our heads over how the brain works.

We’re still scratching our heads over how the brain works.

When I was diagnosed with epilepsy in 2016, I spent countless hours researching the brain disorder in the hopes of understanding it. “Idiopathic,” my neurologist called it, meaning there was no identifiable cause to me suddenly having seizures, literally out of nowhere. It took more than a year to get them under control with the right dosage of anticonvulsant drugs, but I still had no answers. And just when I thought I had run out of resources to continue my research, I started working at the Science History Institute and discovered our digital collections.

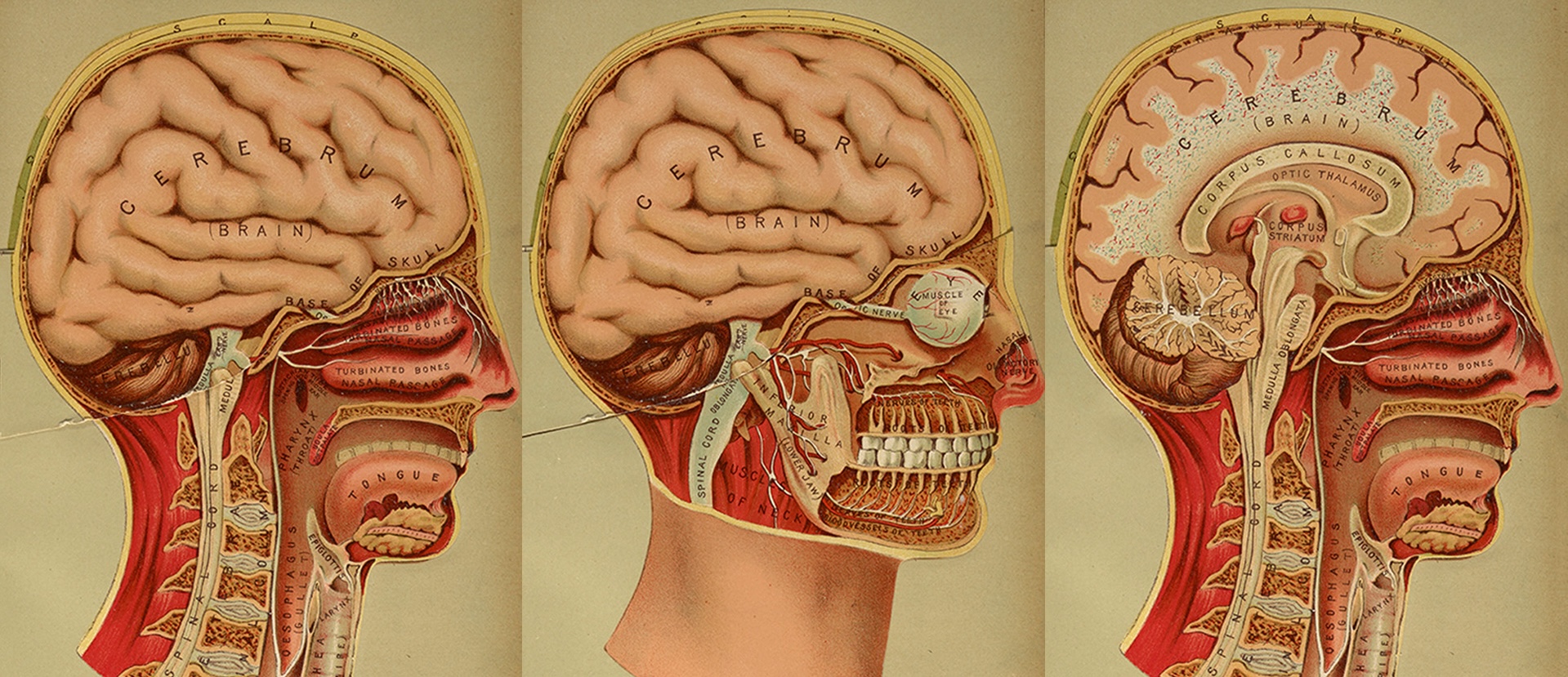

While my search through our rare and modern books, oral histories, videos, photographs, and other items did not uncover the cause of my seizures, I did find lots of brain-related materials and more than a few surprises. One of my favorite finds is from The Book of Health (1898), which includes these color diagrams featuring hinged, paper-flap overlays that progressively fold back to reveal the anatomy of the brain.

What these paper flaps don’t reveal, however, is how the brain actually works. The detail of the illustrations tells us that this 19th-century author knew a great deal about the body’s central organ. But even today, with all of our medical and technological advances, exactly how the brain’s more than 86 billion neurons communicate with each other—and why they sometimes misfire—is still a bit of a mystery.

The ancient Greeks called epilepsy the “sacred disease,” but many other cultures and religions believed that people who experienced epileptic seizures were possessed by demons or spirits, cursed by witches, or somehow “not right with God.” Amulets, prayers, bloodletting, enemas, sacrificial rituals, and even exorcisms were used to get rid of their “fits.”

Perhaps even more shocking than learning about these superstitious—and often deadly—treatments was learning that some of these inhumane methods are still used today. I was equally shocked to learn that in addition to enduring forced sterilization (read: eugenics), people with epilepsy were also forbidden to marry in 17 U.S. states until 1956. Missouri was the last state to repeal the ban in 1980.

I found a few less extreme epilepsy “cures” in our collections, most notably in a publication titled Nostrums and Quackery. Compiled in 1911 by the Journal of the American Medical Association, this volume features a collection of pseudo-scientific printings outlining fraudulent medical treatments, including Dr. Peebles’ Epilepsy Remedy and Dr. Towns’ Epilepsy Treatment. Both were essentially early 20th-century mail order scams, with desperate seizure sufferers sending money in exchange for a miracle cure.

Spoiler alert: there is none.

According to a laboratory analysis by the American Medical Association (AMA), a bottle of Dr. Peebles’ Epilepsy Remedy was nothing more than a “hydro-alcoholic solution of extractives and flavoring” with an “indiscriminate use of bromides” that was actually considered dangerous for people with epilepsy. Peebles, whose degree was from a discredited diploma mill known as the Philadelphia University of Medicine and Surgery, was convicted of fraud in 1903.

The AMA also analyzed Dr. Towns’ Epilepsy Treatment, a brown liquid that smelled like cinnamon and guaranteed a “positive, permanent, and speedy cure” despite a lack of scientific evidence. Federal authorities prosecuted Towns for making false and misleading claims; he pleaded guilty and was fined.

My Water-Cure: Tested for More Than 35 Years and Published for the Cure of Diseases and Preservation of Health (1892) also offers some unique remedies for curing the “falling sickness,” an archaic term for epilepsy that dates back to around 1000 BCE.

Written by Sebastian Kneipp, a German Catholic priest who was one of the forefathers of naturopathic medicine, My Water-Cure claims that “this disease has its principal seat in the blood” and could be cured with a hydrotherapy treatment called “hardening.” Father Kneipp’s healing method calls for patients to “very diligently” walk barefoot through wet grass or on wet stones, take an occasional one-minute cold bath, and wear a wet shirt dipped in salt water once a week.

I’ll let you know if it works.

Epilepsy is best described as a “neurological disorder characterized by a predisposition to recurrent, unprovoked seizures [that] are sudden, uncontrolled electrical disturbances in the brain that can cause a range of symptoms, from subtle changes in behavior or sensations, to severe convulsions and loss of consciousness.” Tonic-clonic (formerly grand mal) seizures like the ones I have cause the latter and are the stereotypical kind you see portrayed in TV shows and movies: blacking out, falling, stiffening of the body (tonic phase), rhythmic jerking (clonic phase), and yes, even tongue biting (not swallowing).

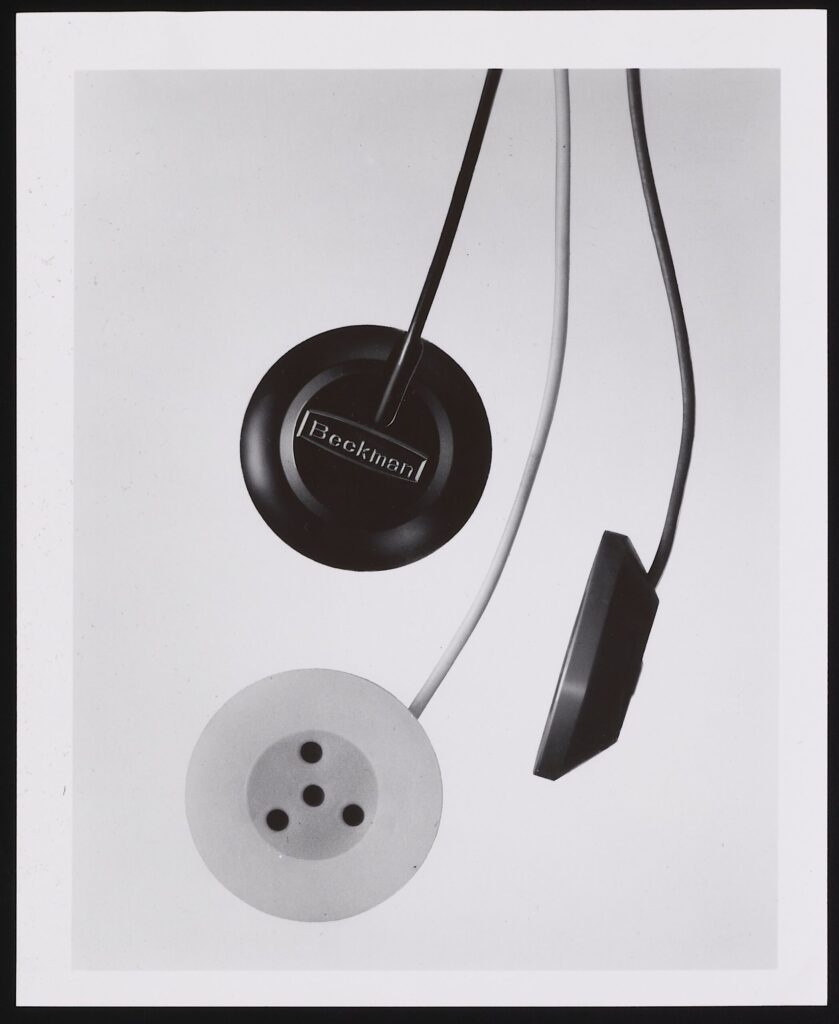

After my second seizure in April 2016, I had an electroencephalogram (EEG), a procedure that records and measures the brain’s electrical activity through electrodes that are attached to the scalp with a special adhesive. The electrodes are then connected to a computer with wires and the activity shows up as wavy lines on the recording. In addition to causing a really bad hair day, my EEG conclusively showed abnormal brain waves consistent with a seizure disorder.

Our digital collections feature several items on electroencephalography, including photos of EEG equipment developed by Beckman Instruments, some of which was used by NASA in the 1960s to monitor the brain activity of astronauts.

I also had an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), a diagnostic test that generates detailed pictures of the soft tissue structure of the brain using a very strong magnet and radio waves. This was done to rule out a tumor, which was thankfully ruled out. I never thought I’d be so happy to hear that my brain is “unremarkable.”

The video above is part of a presentation given in 1990 by Nobel Prize-winning chemist Paul Lauterbur, whose work made the development of the MRI possible. The silent recording shows examples of using an MRI to create 3-D images of the human brain and its internal structures. Dr. Lauterbur’s notebook on the genesis of the MRI and the coconut he used in his imaging research can also be found in our collections.

Learn more about Lauterbur’s coconut in this PhillyVoice article.

You might be as surprised as I was to learn that 1 in 26 people will be diagnosed with epilepsy in their lifetime. The statistics are even more staggering for other brain disorders and conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, migraines, dementia, multiple sclerosis, autism, meningitis, and cerebral palsy. According to the World Health Organization, 1 in 3 people suffer from neurological disorders, which are the leading cause of illness and disability worldwide.

There are also numerous mental and behavioral health conditions that can be caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain, including depression, anxiety, PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), schizophrenia, addiction, bipolar disorder, and ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). In the United States, 1 in 5 adults and 1 in 6 children experience a mental illness each year.

I’m sure you’ve heard the song, “If I Only Had a Brain,” the one sung by the Scarecrow in the 1939 film, The Wizard of Oz. It’s an “earworm” that has been looping in my head nonstop for nine years now (even more so since the recent release of Wicked):

And now it’s looping in your head, too. You’re welcome.

I was seizure-free for four years before having several breakthrough episodes between May 2021 and August 2023. When my husband asked what I wanted for Christmas after the most recent one, I jokingly told him I wanted a new brain. The 3-D model he got me sits on a bookshelf in my home office like a talisman. I don’t want to jinx myself, but so far it seems to be working.

Featured image: Screenshots of the brain from 3-D Display of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Images, a video created using data from MRI inventor Paul Lauterbur, 1981.

You can learn more about epilepsy and other brain disorders by participating in Brain Awareness Week, a global campaign to foster public enthusiasm and support for brain science being held March 10–16, 2025.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.