‘Kurrent’ Events

Deciphering Old German Script in the Bredig Archives.

Deciphering Old German Script in the Bredig Archives.

As a specialist in German language and literature, it seems natural that friends and family members ask me to decipher German language texts. I have always been glad to oblige, whether it was for a friend stationed in Germany who couldn’t understand a utility bill or for my grandmother—the daughter of an Austrian father and a German Mennonite mother—who asked me about an engraving on a culinary heirloom.

Reading German hadn’t perplexed me until I encountered a few late 19th- and early 20th-century letters for my translation work on the Bredig Project at the Science History Institute. These documents were written in Kurrent script and composed by contemporaries of German Jewish physical chemist Georg Bredig.

When I was a student of German literature, the only special German script that we learned (and primarily at the graduate level) was Fraktur. This calligraphic typeface font was designed by Albrecht Dürer and Hieronymus Andreae and used in German-language book publishing from the 16th through the late 19th centuries. While Fraktur is not too different from modern book print and is manageable to learn in a few hours, learning Kurrent has been a new venture requiring much more time, patience, and practice. To many Germanists like me, Kurrent is the quirky handwritten cousin of Fraktur.

As I set out to familiarize myself with Kurrent for translating Georg Bredig’s correspondence, I discovered many fascinating facts about its history. Commonly referred to as “Old German Script” by the English-speaking genealogists and translators who work with it, Kurrent originated in the late Middle Ages as a standardized variant of gothic handwriting. It is defined by its connected letters, rapid curves, and lack of spaces between letters.

Throughout the early Modern Era, many scribes and bureaucrats who employed Kurrent in official documents enhanced it with ornamental features, so that by the 19th century, learning to write German was a complicated endeavor. To simplify the process for schoolchildren, the Berlin-based graphic artist Ludwig Sütterlin invented a form of Kurrent with expansive curves and less angling. By the early 20th century, Sütterlin Kurrent was the most common form of handwriting taught at German schools.

For my colleague Gudrun Dauner, who is a native German speaker and transcribes some of our Kurrent documents before I translate them, the texts are occasionally just as complex for her to interpret, although research helps. Reflecting on this process, Gudrun says, “Although it was hard to read the diversity of the contexts, I was still able to figure out the names and dates that were not known before . . . and it was ultimately rewarding to make an important contribution to this project.”

As Gudrun and I have completed the transcriptions and translations of the Kurrent documents for the Papers of Georg and Max Bredig in the Institute’s digital collections, I would like to share some of our favorite examples.

Postcard from Jacobus H. van ‘t Hoff to Georg Bredig, November 1903.

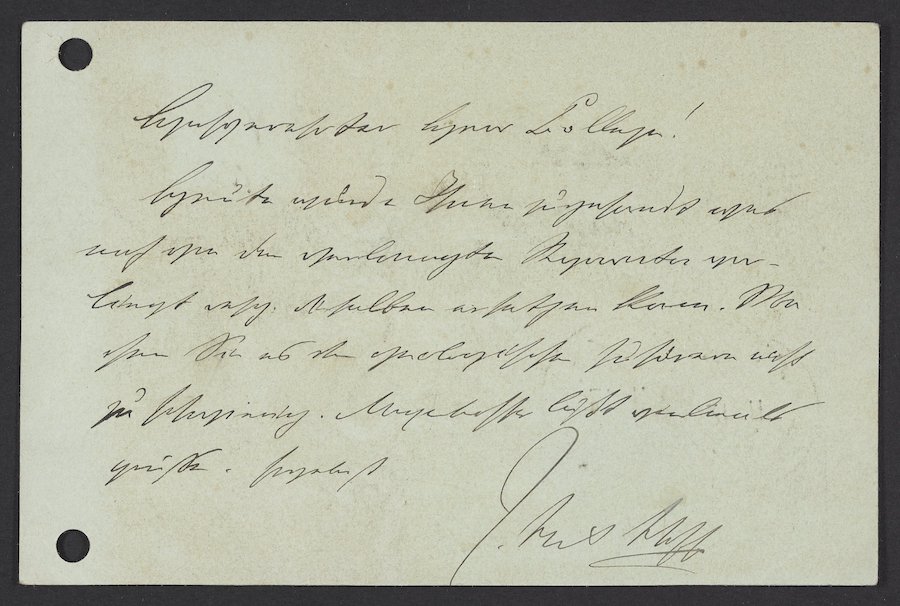

Hochverehrter Herr Kollege!

Heute wurde Ihnen zugesandt was auch von ihm verlangte Reparatur gelingt desg. dieselben ersetzen kann. Machen Sie es den geologischen Justizen nicht zu schwierig. Meyerhoffer läßt vielmals grüßen.

Herzlichst

J. van’t Hoff

Dear Colleague,

Today, you were sent the repair that he requested, which can likewise be replaced. Don’t make it too difficult for the geological authorities. Meyerhoff says hello.

Cordially,

J. van’t Hoff

Jacobus van’t Hoff, a Dutch theoretical physical chemist and close friend of Georg Bredig, often conveyed scientific results and news on postcards in Kurrent. In the note above from November 1903, van’t Hoff informs Bredig of the status of a laboratory equipment repair.

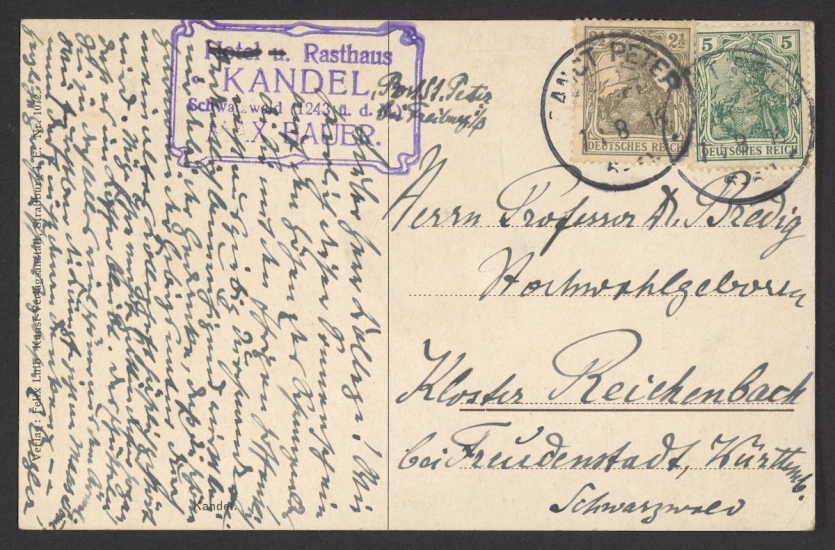

Lieber Herr Kollege!

Wie herrlich dieser Sonnenschein mit den Höhen des Schwarzwalds, die Sie mit den Ihrigen hoffentlich noch ausgiebig durchwandern. Ordentlich beruhigend wirkt bei mir dabei der Gedanke, daß die schöne Harmonie der Gebirgsnatur durch mein altes Kollegstift füglich gekürt wird. Möge Ihre nächste Hüttentour sogar, daß es im Koffer bleibt. Das schütteln Sie ja doch alles nie schöner aus dem Ärmel. Wie fruchtbar die Kunst jetzt an Malers Sonne; man darf nicht daran denken.

Herzliche Grüße Ihres ergebensten

C. Engler

Dear Colleague,

This sunshine in this altitude of the Black Forest, which you and your family will hopefully hike through extensively, is wonderful. The thought that my former colleague is enjoying the beautiful harmony of the mountains has a very calming effect on me. I hope you can take your memories of your journey home with you! You can never plan such a trip in a better way! Art is flourishing now in the painter’s sun. I must not think of it.

Warm regards.

Yours sincerely,

C. Engler

Carl Engler, a German chemist known for his work on indigo, sent a postcard (above) in Kurrent in the summer of 1916 to Georg Bredig while on vacation in the Black Forest. Engler wishes his former colleague well and suggests activities to do with his family in the region.

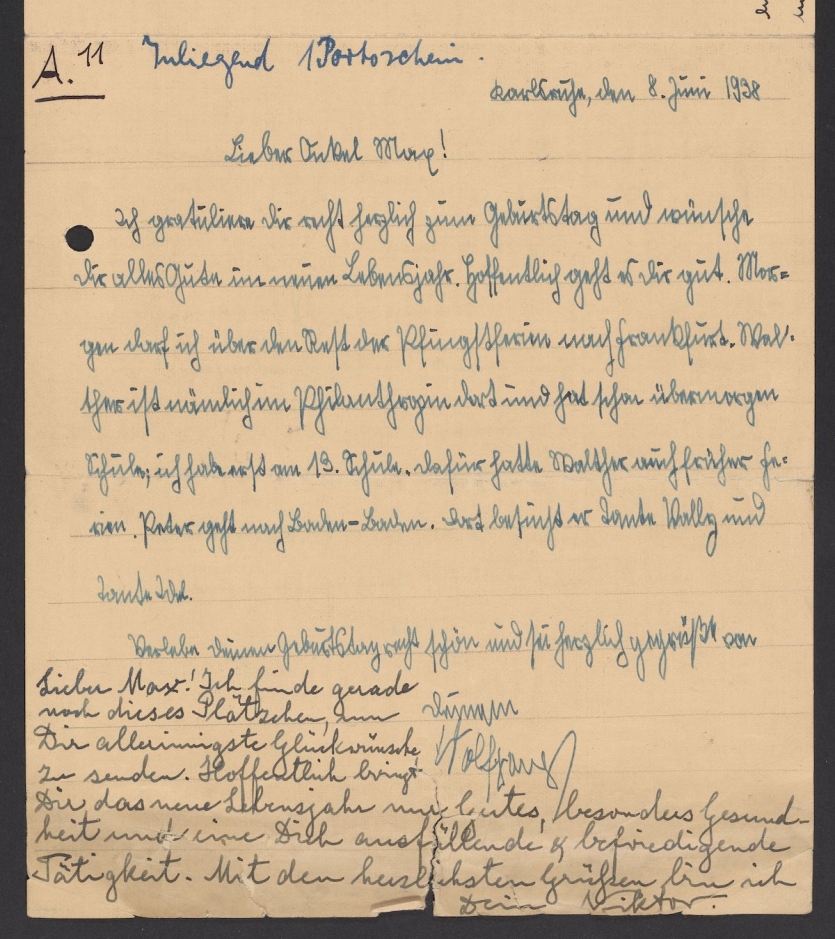

The use of Kurrent declined in Germanophone countries throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Many individuals who previously wrote in Kurrent reverted to Latin-based script, a change that can be observed in the Bredig archive. For example, in one 1938 joint birthday letter from the Homburger family to Georg Bredig’s son, Max Bredig, parents Viktor and Marianne Homburger use Latin script, while their children use Sütterlin Kurrent script.

In a dark turn, Kurrent seemed to vanish completely from German language correspondence after 1941, especially when the Third Reich maliciously issued a deceptive decree that Kurrent was of Jewish origin. The true intent of the regime, however, was to make the German language easily accessible to everyone in newly annexed countries where the script was not used.

While Kurrent was no longer taught or used, some German speakers chose to learn it independently or in classes from the 1950s onward. As a result, Kurrent became a “Geheimschrift” (or secret script) that only specialists could understand. Yet in English-speaking countries throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Kurrent has experienced a resurgence among people of German heritage for genealogical purposes. In a Kurrent workshop that I attended in May 2022 at the German Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, some participants shared their wishes to read German ancestral documents.

Fancy learning Kurrent on your own? Handbooks such as Tips and Tricks of Deciphering German Handwriting: A Translator’s Tricks of the Trade for Transcribing German Genealogy Documents by Katharina Schober and Deutsche Kurrentschrift – Übungsbuch by Chris Nöhrenberg have been immensely valuable to me.

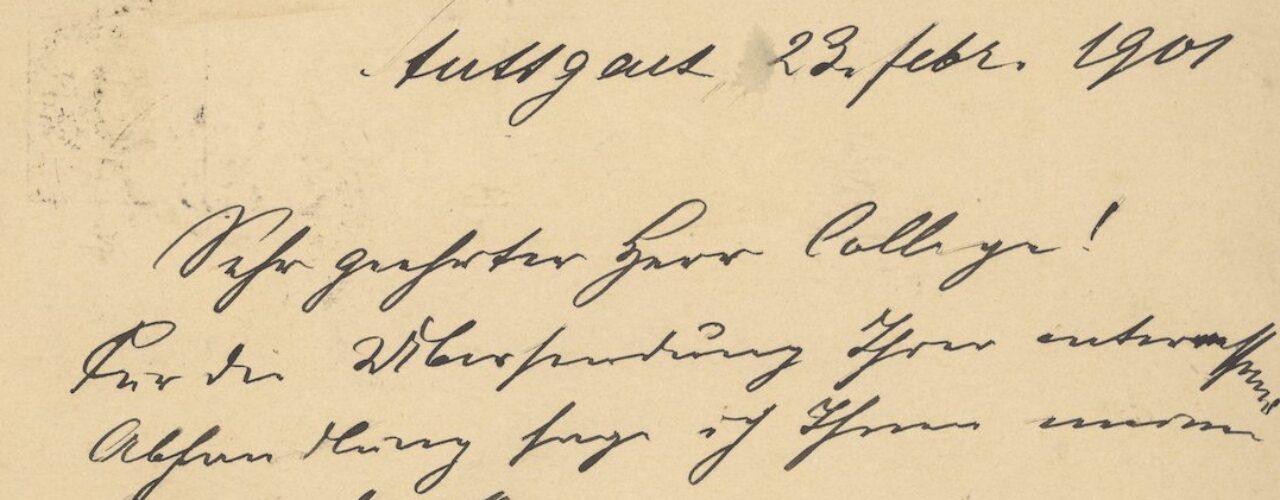

Featured image: Back of Postcard from Carl Magnus von Hell to Georg Bredig, February 23, 1901.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.