Science History Institute to Debut New Outdoor Exhibition on October 24

‘Science and Survival’ features enlarged reproductions of photographs and telegrams rescued from Nazi-occupied Germany installed on the façade of the Institute’s Old City building.

First Friday public opening and curator’s talk scheduled for November 4, 5pm–7pm.

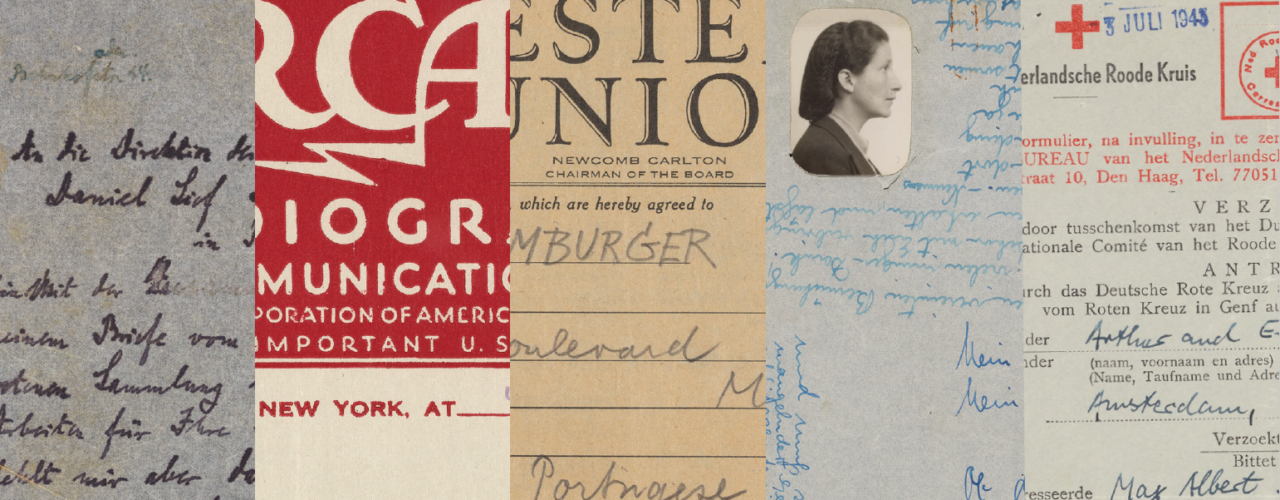

On October 24, 2022, the Science History Institute will debut Science and Survival, a new outdoor exhibition featuring enlarged reproductions from a recently digitized collection of telegrams, postcards, and letters belonging to Georg and Max Bredig, German father and son chemists of Jewish descent. The intimate correspondence reveals the harrowing story of the Bredig family’s struggle to escape the horrors of the Third Reich.

Science and Survival will be installed on the façade of the Institute’s building at 315 Chestnut Street in Old City Philadelphia. A free, public opening and curator’s talk is scheduled during First Friday, November 4, 5pm–7pm. The exhibition is drawn from the Papers of Georg and Max Bredig collection, which is available to the public for free in our digital collections.

“We hope the installation inspires people to explore the digital archives further,” said Michelle DiMeo, vice president of collections and programs and the Arnold Thackray Director of the Othmer Library. “It’s amazing to see how the scientific network built by father and son morphed into personal connections that ensured their very survival.”

Through the generous support of the Council on Library and Information Resources, the Institute has spent the past two years transcribing, cataloguing, translating, and digitizing nearly 3,000 letters, photographs, and other historical materials from the Bredig family archives. The existence of such papers is quite rare, as many archival collections of Jewish scientists were seized and destroyed by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

Georg Bredig (1868–1944) was a pioneering scientist in the field of physical chemistry who held important academic positions until his career was ended by the Nazis in 1933. The pre-1933 materials document Bredig’s early scientific training and his rise to international prominence during the golden age of German science. The collection contains extensive correspondence with many Nobel laureates in chemistry and physics, including Svante Arrhenius, Wilhelm Ostwald, Niels Bohr, Ernest Rutherford, Fritz Haber, Max Planck, Walther Nernst, and Harold Urey.

The post-1933 papers illuminate in extraordinary detail how the Bredig family tapped into their network to escape Nazi-occupied Europe. Georg’s son, Max Bredig (1902–1977), who was also a chemist, left for the United States in 1937. Georg, his daughter, Marianne, and her husband, Viktor Homburger, remained in Germany at first.

The papers describe Georg, Marianne, and Viktor’s increasingly desperate plight, and Max’s heroic efforts to secure humanitarian aid, transit permits, transport, visas, and offers of employment in the U.S. for his family and colleagues.

The collection includes hundreds of documents related to the confiscation of family assets, Georg’s and Viktor’s arrests during Kristallnacht, Georg’s expulsion from his university position in Karlsruhe, and his attempts to leave Germany, which took him to the Netherlands and ultimately New York City in 1939.

Among the most surprising finds are letters to Max Bredig from German Jewish chemist Alfred Schnell and his wife, Eva, composed while in hiding on a Dutch farm during the Nazi occupation. These short messages were sent through the Red Cross and were often written in code or using aliases to protect their identities. The Schnells were arrested and executed by Dutch police loyal to the Nazis in 1944. Max only learned of their terrible fate from a lengthy letter—also in the collection—that he received just after the war.

Science and Survival features snippets of all these stories.

“It’s a story we have heard time and time again, but it’s a story we should continue to tell,” said Jocelyn McDaniel, research curator of the Bredig Project who has spent the last two years translating the collection. “The Bredig family took great risks to ensure not only their survival, but also the preservation of Georg Bredig’s scientific accomplishments. We’re grateful to the Bredig family for entrusting us to preserve and interpret these materials. The process of bearing witness to Holocaust memory is particularly significant in the 21st century as new generations are tasked with teaching about this harrowing time.”

In addition to the First Friday public opening and curator’s talk on November 4, the Institute is hosting a virtual Varsity Tutors class titled “War, Science, and Survival” taught by McDaniel, highlighting unique aspects of the Bredig Archives through our collections blog, and publishing articles about the collection in our Distillations magazine.

The Science History Institute thanks the Walder Foundation for its generous support of the acquisition of the Papers of Georg and Max Bredig. Digitization and cataloging of this collection was made possible through the generosity of the Council on Library and Information Resources. Additional support comes from Aetna CVS Health Community Partnership Initiatives, Ari Kaplan, and Vidya Plainfield.

More Press

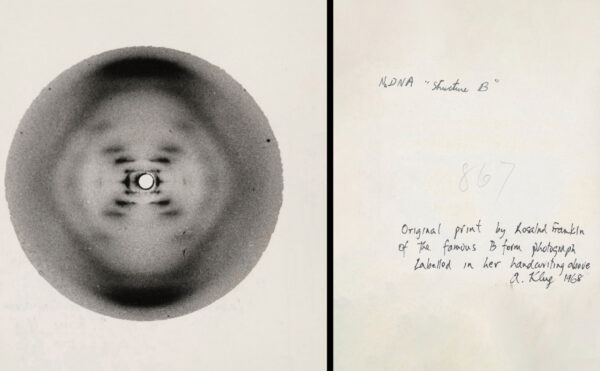

Science History Institute Acquires Molecular Biology Archive That Includes Rosalind Franklin’s Historic ‘Photo 51’

This unparalleled collection documents the race to identify DNA’s double-helix structure and other significant developments that formed the foundation of molecular biology.

Science History Institute Celebrates ‘Earthly Matters’ Exhibition Opening and Lobby Renovation with Ribbon Cutting on October 8

Visitors are invited to Old City for an up-close look at our new collection of minerals, a curator’s talk, light refreshments, and more.

Science History Institute’s Annual Curious Histories Fest Asks ‘What’s for Lunch?’

The free, daylong celebration of the history of food science takes place Saturday, June 14, 11am–3pm.