Science History Institute’s New Exhibition Asks: What’s Behind the School Lunch?

Lunchtime: The History of Science on the School Food Tray opens September 27.

The Science History Institute is pleased to present Lunchtime: The History of Science on the School Food Tray, an exhibition that delves into the surprising backstory behind one of the most familiar rites of passage—eating a school lunch.

Ring the Bell, It’s Lunchtime! An Opening Celebration takes place on Friday, September 27, 2024, 5pm–8pm at 315 Chestnut Street in Old City Philadelphia. This free event features a school lunch-inspired tasting, curator’s talk, lunch-themed quizzo, and much more.

There was a time when food was food, rather than vitamins, calories, fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. Lunchtime begins there, reaching back as far as the late 18th century and its flurry of scientific discoveries, and continuing onward through the 19th century and to the early 20th century.

By this time, compulsory education had become the law, ideas about childhood were changing, and many Americans were leaving the farm for the city, where they could no longer be sure about the sources of their food. The exhibition continues up to the present day, applying the lens of science to a veritable petri dish of politics and popular culture.

A subtext is the rapid professionalization of American women. Newly trained as dieticians, home economists, and educators, women were often on the front line advocating for a nationwide school lunch program and driving conversations about welfare, children’s health, and poverty.

“This exhibition tucks a complex story of scientific and technological change, and the social forces they influenced and were influenced by into a simple conceptual framework—the school lunch tray,” says exhibition curator Jesse Smith, the Institute’s director of curatorial affairs and digital content.

He concludes, “We hope it will surprise our visitors to learn how so many of the ideas taken for granted today—like the fact that vitamins are a group of food compounds necessary for health—are in fact relatively recent scientific discoveries and shape the way we feed the country’s schoolchildren.”

Dr. Smith has organized Lunchtime at the Science History Institute, which is located at 3rd and Chestnut Streets in Philadelphia. Alusiv, a cross-disciplinary design team based in the city, designed the exhibition to evoke the places where students eat, as well as the places where food is studied, grown, produced, cooked, and served.

On View in Lunchtime

Rare scientific instruments, posters, pamphlets, photographs, and period editions of books popularizing new ideas about a “proper” diet are among the 90 artifacts on view.

One of the first items encountered by the Lunchtime visitor is a delicate hand-tinted illustration from a book published in London in 1801 showing a calorimeter, a funnel-like apparatus devised in the early 1780s by the French scientists Antoine Lavoisier and Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace. The pair used a guinea pig to ascertain whether respiration is a form of combustion.

Nearby are other books, prints, and photographs that speak to still more scientific breakthroughs, such as Nicholas Appert’s experiments into canning food in tin on a large scale to meet the needs of the French military; the French surgeon François Magendie’s research using live animals; the British chemist and physician William Prout’s findings about digestion; the French chemist Jean-Baptiste Boussingault’s studies to understand the value of nitrogen; and American physiologist Wilbur Atwater’s respiration calorimeter, a chamber large enough to accommodate a human subject for several days to monitor food going in and waste coming out.

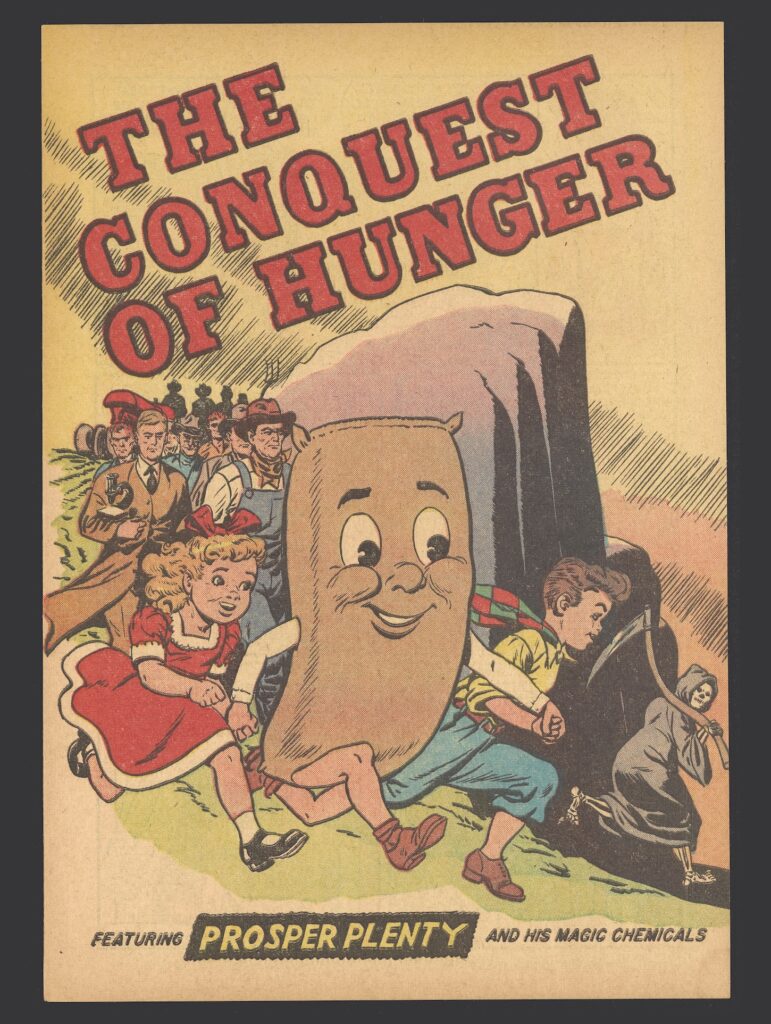

Amid the scientific materials, two comic books stand out: an issue of Real Life Comics (1943) portraying an American doctor, Joseph Goldberger, as a superhero who identifies nutritional deficiencies as the cause of pellagra, and The Conquest of Hunger (1951), a comic strip published by the National Fertilizer Association that features a cover illustration of a bag of chemical fertilizer running hand-in-hand with a girl and boy.

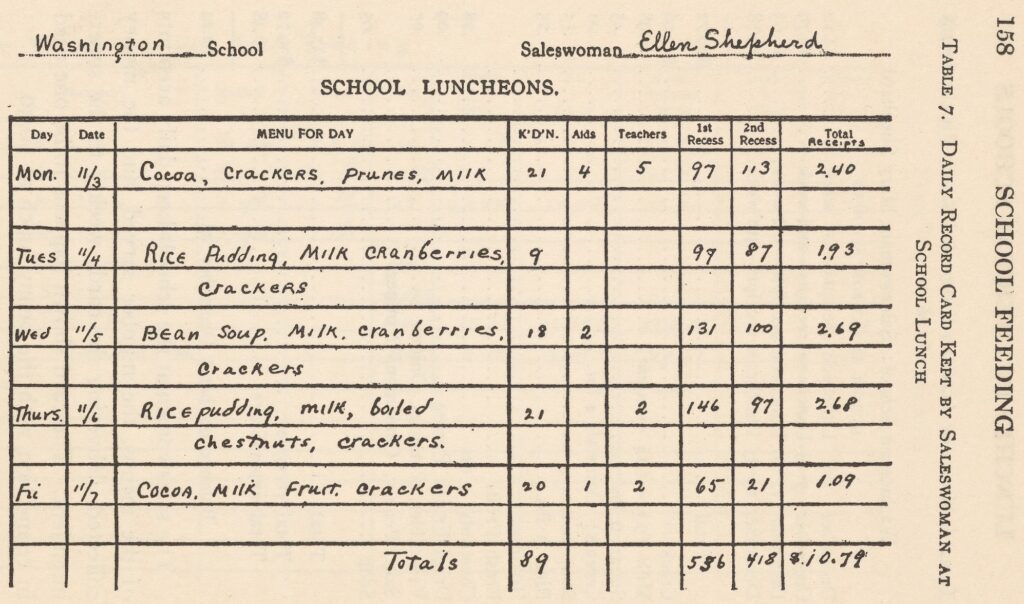

Another featured item is a tiny aluminum token, which in 1909 would have purchased lunch in a Philadelphia school. In Lunchtime, this sliver of metal speaks to the city’s role in piloting penny lunches and jumpstarting a nationwide discussion around schoolchildren’s access to food. Today, a time when 16% of Philadelphia households face food insecurity, that conversation is still going on among community advocates, educators, and city, state, and federal officials.

The Chemistry of Food

In Lunchtime, a number of historic scientific instruments are also on display, including a polarimeter, which measures the angle of a beam of light passing through a solid substance; a refractometer, which measures how light bends when passing through a liquid; a Babcock tester that spins milk samples to separate out fat content to spot dilution; a butyrometer for determining fat content in dairy products; a spectrophotometer, which advanced the measuring of chemicals in food; a Beckman DU ultraviolet spectrophotometer, which reduced from weeks to minutes the process of finding vitamin A in food; and a Beckman gas chromatograph, which separates and quantifies food components, leading researchers to refine dehydration processes—and the government to help invent instant mashed potatoes.

For the contemporary viewer, the most unrecognizable device may well be one of the simplest: a fireless cooker, which resembled a large wooden box where a child could put a homecooked meal to be boiled and kept until lunchtime. This invention helped extend the school lunch to rural districts, especially in the South, where there were no centralized school kitchens. One takeaway from Lunchtime is the difficulty of feeding schoolchildren nationwide. The administration of school lunches was left to state and local authorities, often perpetuating existing racial inequalities, especially in the South, where 90% of the country’s Black population lived.

The Art of School Lunch

The federal government is shown to have played a continuous leading role in the development of the school lunch. As suggested by a vintage bag of Pioneer brand hybrid seed corn (circa 1935–1970), improvements to seeds and fertilizers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries translated to food surpluses even during the Great Depression. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) pushed for the distribution of surpluses to schools—sometimes at the expense of nutrition. At the same time, the Works Progress Administration jumped in to cook lunches and exhort Americans to eat healthily, as can be seen in a poster reading “Vitamins Pack a Punch into School Lunch” (1931–1941).

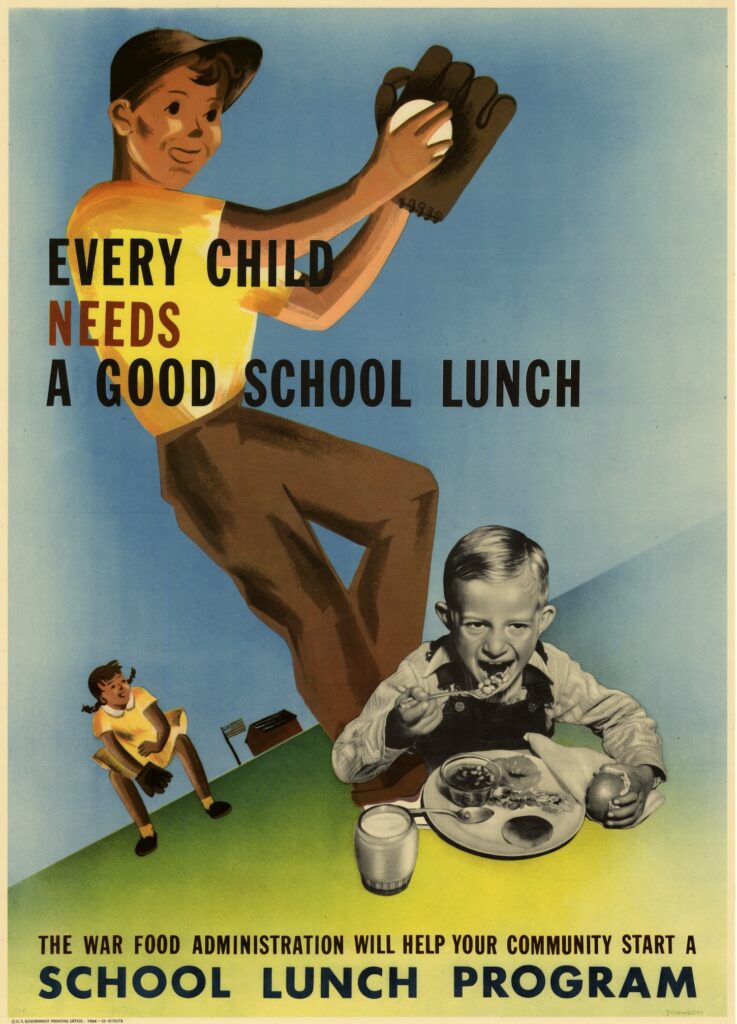

Research by the U.S. military accelerated widespread acceptance of subsidized school lunches before and during WWII. The country’s looming entry into the war drove a sense of urgency reflected in the establishment of the War Food Administration, which, among other initiatives, produced posters like the featured “U.S. Needs Us Strong…Eat Nutritional Food” (1943) and “Every Child Needs a Good School Lunch” (1944).

From Fresh to Frozen to Fresh

The USDA was behind the effort to perfect the processes of dehydrating and freezing food, leading to commercial products like the Swanson frozen dinner displayed in Lunchtime. Other material innovations that extended the reach of the school lunch were cellophane (made of cellulose) and Saran Wrap (made of synthetic polyvinylidene chloride plastic), produced by DuPont and Dow Chemical Company, respectively. The Institute highlights the benefits of innovations like frozen dinners and plastic wrap while also citing the unintended consequences of these and other new materials.

In 1973 the Super Sandwich board game was widely marketed as a game for the whole family. Its objective was to concoct a sandwich out of any assortment of foods that provided the Recommended Daily Allowance of protein, calcium, iron, vitamin A, vitamin B-complex, and vitamin C without exceeding the daily calorie recommendation.

As the visitor moves into the present day, Lunchtime illustrates the increasing reliance on frozen and packaged foods, from Lunchables to pizza, and more positively, the nascent movement toward sourced and seasonal fresh food. Playing a starring role here as a healthy lunch alternative is a package of Rebel Crumbles, a breakfast food devised and marketed by Rebel Ventures, a group of teen and young adult entrepreneurs based in West Philadelphia. The crumble meets USDA guidelines and is distributed in Philadelphia public schools for breakfast.

American Women In the Lead

Cameos of women who advanced the cause of the school lunch run throughout Lunchtime. Among those featured is Jean Fairfax, the founder of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund who oversaw the Committee on School Lunch Participation in 1968, the year it issued Their Daily Bread, a report finding that only 4% of schoolchildren in America received free and reduced-cost lunches. Public anger over this report and other reportage led to increased funding for school lunches.

# # #

About the Science History Institute

The Science History Institute is a rarity—a museum and library dedicated to uncovering the hidden stories behind the history of science, rather than the science of science. Founded in 1982 and located in Old City Philadelphia, the Institute collects, preserves, interprets, and shares objects, content, and images exploring lesser-known and sometimes overlooked stories from the history of science and technology. We dive deep into the history of scientific successes and failures, with a focus on expanding the public’s understanding of how science and society intersect.

As the Science History Institute looks forward, our research, storytelling, public programming, and educational outreach will continue to reflect these diverse and compelling histories and to challenge perspectives by applying a critical lens to past theories and harmful practices.

Sponsorship

Major support for Lunchtime has been provided by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, with additional support from the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Foodology by Univar Solutions, Quaker Houghton, and Fred and Elizabeth Weber.

About The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage

The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage is a multidisciplinary grantmaker and hub for knowledge-sharing, funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts, dedicated to fostering a vibrant cultural community in Greater Philadelphia. The Center invests in ambitious, imaginative, and catalytic work that showcases the region’s cultural vitality and enhances public life, and engages in an exchange of ideas concerning artistic and interpretive practice with a broad network of cultural practitioners and leaders.

Media Requests

Caitlin Martin, cmartin@sciencehistory.org, 215-873-8292

Anne Edgar, anne@anneedgar.com, 646-567-3586

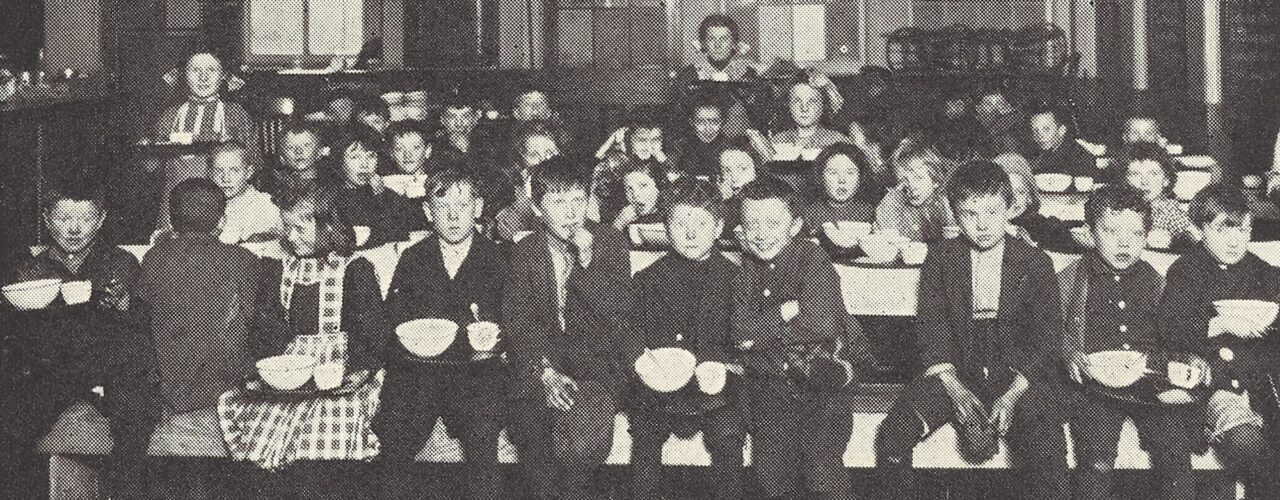

Featured image: Three-cent dinner in Philadelphia schools, from School Feeding: Its History and Practice at Home and Abroad, 1913.

More Press

Science History Institute to Install New Exhibit Space, Renovate Lobby, and Add Digital Production Studio and Gift Shop

Our museum will be temporarily closed until March 19, 2025, with a new exhibition slated to open in May 2025.

Science History Institute’s 2nd Annual Curious Histories Fest Will ‘Color Your World’

The free, daylong celebration of all things color takes place Saturday, June 8, 11am–3pm.

Science History Institute’s ‘Lunchtime’ Project Receives Major Grant from The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage

$289K+ award will support exhibitions, articles, and public programming examining the history of the U.S. school lunch program through the lens of food science.