Science History Institute Receives CLIR Grant to Digitize Papers of Georg and Max Bredig

Collection smuggled out of Nazi Germany tells story of noted Jewish German scientist’s rise to prominence and the Bredig family’s struggle to survive the Holocaust.

The Science History Institute has been awarded a $198,454 grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) for the project Science and Survival: Digitizing the Papers of Georg and Max Bredig. The Institute’s project was one of only 16 selected from a pool of 151 applicants for CLIR’s Digitizing Hidden Collections grant program funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Unlike many other archival collections of Jewish German scientists that were seized and destroyed by the Nazis, Georg Bredig’s papers miraculously survived. This award will be used to catalogue, translate, digitize, and make publicly accessible nearly 3,000 letters, photographs, and other documents from this newly rediscovered trove of rare historic material as well as the related war-time papers of Max Bredig, Georg’s son.

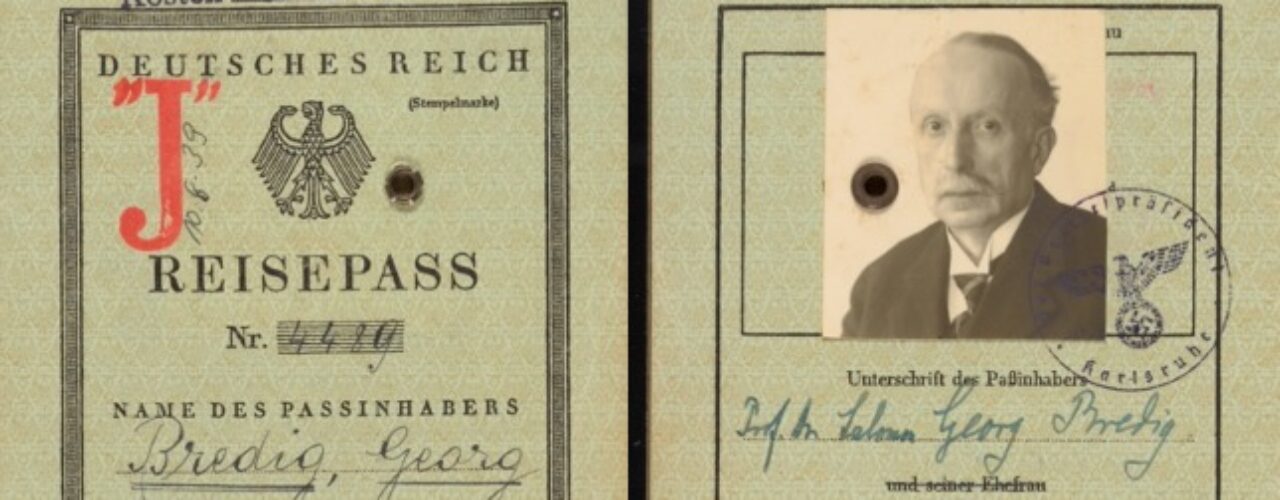

Georg Bredig (1868–1944) was a pioneering scientist in the field of physical chemistry who held important academic positions until his career was ended by the Nazis in 1933. The pre-1933 materials detail Bredig’s early scientific training and his rise to international prominence during the golden age of German science. The collection contains extensive correspondence with many Nobel laureates in chemistry and physics, including Svante Arrhenius, Wilhelm Ostwald, Niels Bohr, Ernst Rutherford, Fritz Haber, Max Planck, Walther Nernst, and Harold Urey.

This archive attests not only to Georg Bredig’s significant scientific contributions, but also to his and his family’s struggle to survive the Holocaust. Like his father, Max Bredig (1902–1977) trained as a chemist but after witnessing the rising tide of anti-Semitism, he left for the United States in 1937. Georg Bredig, his daughter, Marianne, and her husband, Viktor Homburger, remained in Germany although the Homburgers’ three young sons were relocated to England through the Kindertransport rescue mission.

The post-1933 papers describe—in highly intimate and often harrowing detail—Georg, Marianne, and Viktor’s increasingly desperate plight, and Max’s heroic efforts to secure for his family and colleagues’ humanitarian aid, transit permits, transport, visas, and offers of employment in the United States.

The Bredig collection has hundreds of documents related to the confiscation of family assets; Georg’s and Viktor Homburger’s arrests during Kristallnacht; and Georg’s expulsion from his university position in Karlsruhe and his attempts to leave Germany, which took him to the Netherlands and ultimately New York City in 1939.

There are 125 letters and telegrams from Viktor and Marianne Homburger written during and immediately after their internment at Camp de Gurs in southwest France. The collection also contains letters from chemist Fritz Hochwold written while he was imprisoned in Miranda del Ebro Camp in Spain, with envelopes showing they had been opened by camp guards.

Among the most surprising finds are letters to Max Bredig from the Jewish German chemist Alfred Schnell and his wife, Eva, composed while in hiding on a Dutch farm during the Nazi occupation. These short messages were sent through the Red Cross and were often written in code or using aliases to protect their identities. The Schnells were arrested and executed by Dutch police loyal to the Nazis in 1944. Max only learned of their terrible fate from a lengthy letter (also in the collection) that he received just after the war.

Georg Bredig lived in fear that his archives would be destroyed by the Nazis and so, at great risk, he shipped his books and papers from Germany to the United States in 1938 where they were received by Max. “‘Science and Survival’ fulfills Georg Bredig’s wish that this collection would be preserved for future generations to study,” said project director Hillary Kativa, the Institute’s chief curator of audiovisual and digital collections.

“The Science History Institute has exceptional archival and oral history collections documenting the experiences of émigré scientists in multiple historical contexts,” said David A. Cole, president and CEO of the Institute. “The Bredig papers, acquired in 2019 through the generosity of the Walder Foundation, adds to this institutional strength. We are very grateful for CLIR’s support, which will bring this once truly hidden collection to wider scholarly and public attention.”

About the Council on Library and Information Resources

The Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) is an independent, nonprofit organization that forges strategies to enhance research, teaching, and learning environments in collaboration with libraries, cultural institutions, and communities of higher learning. To learn more, visit clir.org and follow CLIR on Facebook and Twitter.

Image above: Georg Bredig’s German passport, 1939.

Science History Institute

More Press

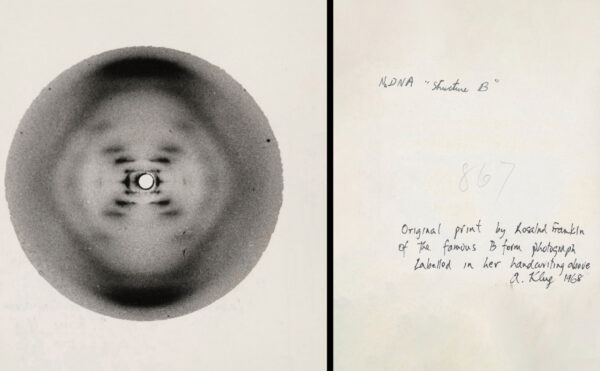

Science History Institute Acquires Molecular Biology Archive That Includes Rosalind Franklin’s Historic ‘Photo 51’

This unparalleled collection documents the race to identify DNA’s double-helix structure and other significant developments that formed the foundation of molecular biology.

Science History Institute Celebrates ‘Earthly Matters’ Exhibition Opening and Lobby Renovation with Ribbon Cutting on October 8

Visitors are invited to Old City for an up-close look at our new collection of minerals, a curator’s talk, light refreshments, and more.

Science History Institute’s Annual Curious Histories Fest Asks ‘What’s for Lunch?’

The free, daylong celebration of the history of food science takes place Saturday, June 14, 11am–3pm.