Archive Smuggled from Nazi-Era Germany Acquired by the Science History Institute

The collection of Jewish German chemist Georg Bredig documents the early pioneers of physical chemistry in Europe and the struggles of Jews trying to escape the Nazis.

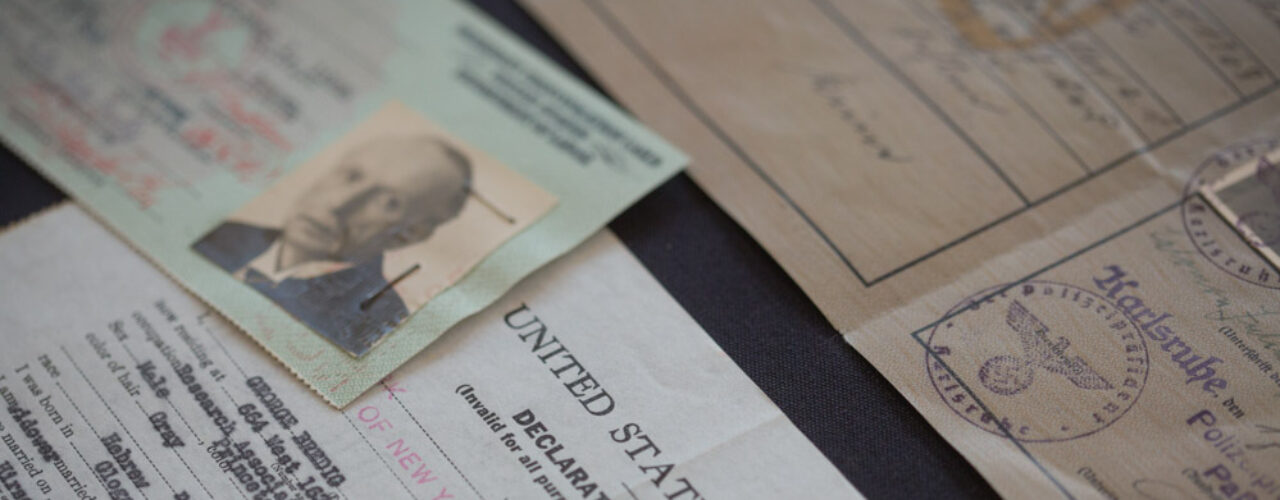

The Science History Institute has acquired an amazing collection of correspondence, books, photographs, and scientific notes belonging to Jewish German chemist Georg Bredig. The collection spans decades, from the late 19th century, just as the field of physical chemistry was emerging, to the 1930s and the horrors faced by the Jewish community as the Nazis rose to power. The archive has never been made public. This acquisition was made possible by the generous support of the Walder Foundation.

“Bringing this collection to the Science History Institute fulfills Georg Bredig’s wish that these documents be preserved so that future generations can study them,” said former Institute president and CEO Robert Anderson. “They are significant not only to scholars of the history of science but to Holocaust scholars as well.”

“As long-time funders of Holocaust education, Dr. Walder and I are proud to support the acquisition of the Bredig archive,” said Elizabeth Walder, president and executive director of the Walder Foundation. “We know that this collection will provide history and science scholars alike a unique vantage point for uncovering some of the untold stories of this tumultuous period in world history.”

Bredig introduced the model reaction methodology to catalytic research, discovered and explored new catalytic phenomena, and discovered and investigated asymmetric catalysis. Further, he explored the relationships between catalytic activity and the physical state of metals. The earliest documents in the archive—from the late 19th century—provide a snapshot of the field of physical chemistry in its early years. There is extensive correspondence with the founding fathers of the field, including many early Nobel laureates in chemistry, such as Jacobus Henricus van’t Hoff, Svante Arrhenius, Fritz Haber, and Wilhelm Ostwald.

The post-1933 collection items document a very different story. Bredig, along with his family and Jewish colleagues, struggled to survive under the increasingly oppressive Nazi regime. Some managed to flee to other countries, while others were not so lucky. Their stories unfold through the letters describing their situations in detail, from requests for food and clothing for detainees to the desire to resume their work and their normal routines. Many of the letters and documents relate to Bredig’s attempts to leave Nazi-occupied Europe. Included in the collections are his German identification papers and passport, both marked with a “J.”

Bredig recognized the Nazis would likely destroy his personal library and archive, and his efforts to ensure its survival nearly cost him his life. In a letter to his son, Max, in 1939, Bredig writes, “Yesterday I sent as a package to you the three green volumes I–III of my opera omnia. The rest IV–VII in green volumes will follow in the next week or so. . . . It is very dear to me that after my death the one and the other will end up in good hands (for an obituary and also for reference). In case you don’t want to keep it, give it to a university library, preferably one abroad, or to a good friend. Under no circumstances do I want it to be wasted/lost, given away or tossed! It should give witness over my life’s work.” The collection was smuggled out of Nazi Germany to the van’t Hoff laboratory in the Netherlands, where it remained for the duration of the war. In 1946 it was shipped to the Bredig family in the United States.

Funding from the Laurie Landeau Foundation will provide for conservation and preservation of the archive. The Institute plans to make the collection available to researchers and to develop related public programming in the coming months.

About Georg Bredig (1868–1944)

Georg Bredig had a distinguished career in chemistry and as a professor. He held teaching positions at universities throughout northern Europe before being appointed professor for physical chemistry at the Technische Hochschule in Karlsruhe, Germany, in 1911. In 1933 the Nazis forbade Jews to hold professional positions. Bredig’s credentials as a scientist were revoked, and he was forced into retirement. In 1938, during Kristallnacht, he was arrested but later released. Bredig fled Germany in 1939 with the assistance of a fellow Jewish chemist, Ernst Cohen. Many of Bredig’s colleagues, friends, and family members were not so lucky. Cohen perished in the gas chambers at Auschwitz. Alfred Schnell, a chemist and colleague of Bredig’s son was executed, along with his wife, by Dutch soldiers loyal to the Nazis. They had been in hiding in the Netherlands for years, and their story is now well known. But the fact they were writing letters while in hiding was completely unknown until this collection surfaced.

Max Bredig left Germany two years before his father and immediately set to work getting the rest of his family out of Europe as well as helping others do the same. Bredig’s daughter, Marianne, along with her husband, Viktor, spent nine months in the Gurs internment camp in France before finally making it to the U.S. in 1941. After Bredig received a letter with an offer of a position from the president of Princeton University in November 1939, Max was finally able to obtain a visa for his father. Georg Bredig came to the United States in 1940. In poor health, he stayed with his son in New York City until his death on April 24, 1944.

About the Walder Foundation

The Walder Foundation is a private family foundation based in the Chicago area that provides organizations and individuals with resources and tools to build a sustainable future through strategic programs focused on performing arts, advancing sustainability, immigrant advocacy, Jewish life, and science innovation.

Media Coverage

This announcement was mentioned in a number of local, national, and international publications including the PhillyVoice and Hamodia, a daily newspaper for the Jewish community.

More Press

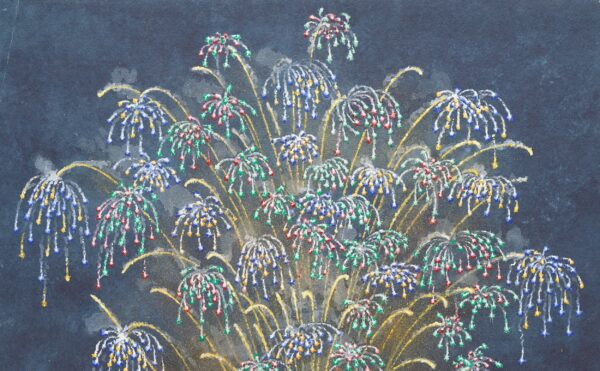

Science History Institute’s New Exhibition Explores the Sparkling and Explosive History of Fireworks

Flash! Bang! Boom! opens April 10 as part of America’s 250th birthday celebration.

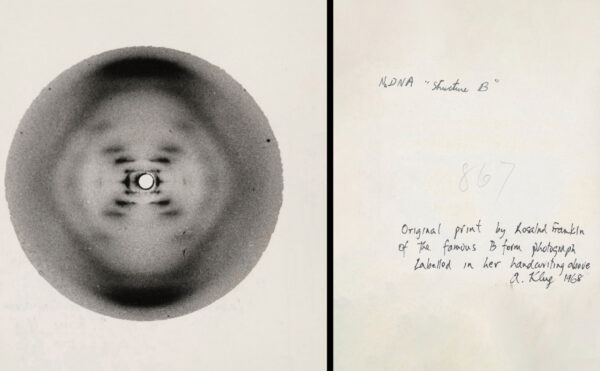

Science History Institute Acquires Molecular Biology Archive That Includes Rosalind Franklin’s Historic ‘Photo 51’

This unparalleled collection documents the race to identify DNA’s double-helix structure and other significant developments that formed the foundation of molecular biology.

Science History Institute Celebrates ‘Earthly Matters’ Exhibition Opening and Lobby Renovation with Ribbon Cutting on October 8

Visitors are invited to Old City for an up-close look at our new collection of minerals, a curator’s talk, light refreshments, and more.